The large intestine, sometimes collectively referred to as the colon or large bowel, is the final sequence of segments in the gastrointestinal tract. After you swallow food, It takes the bolus about eight to nine hours to reach, in the form of chyme residue, the large intestine. As the chyme passes through the large intestine, water and electrolytes that were not absorbed in the small intestine are further taken up. This water content reduction forms semi-solid feces for excretion. As degraded chyme remains in the large intestine for 12 to 24 hours, the efficiency of water removal is high. Of the approximate 1.5 liters (around 0.4 gallons) of water entering the large intestine each day, only about 100 milliliters (roughly 0.4 cup) remain in the feces at the time of elimination.

The large intestine contains about one kilogram (2.2 pounds) of microbes and about 10 different types of bacteria that further aid in chemical digestion prior to excretion.

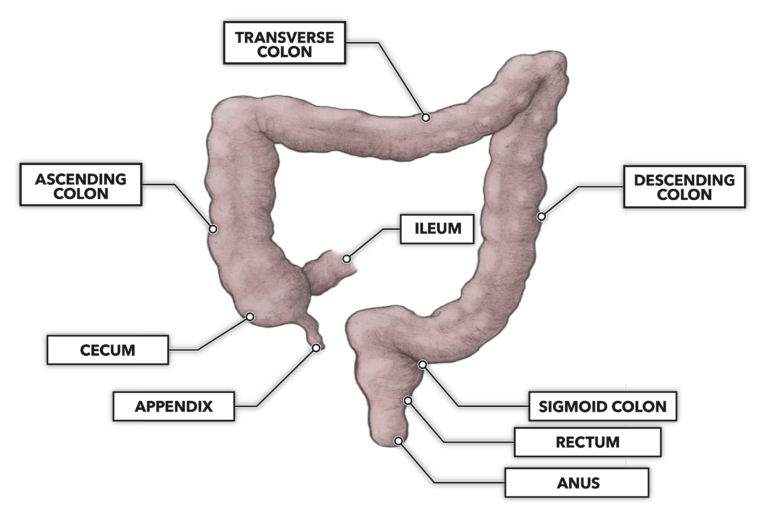

The large intestine is a gated continuation of the gastrointestinal tube. The last segment of the small intestine, the ileum, is followed by eight segments of the large intestine: cecum, appendix, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, rectum, and anus. Anterior view.

The large intestine is approximately 1.5 meters (about 4.9 feet) in length, though this will vary according to individual body dimensions. The diameter of the large intestine is much larger than the small intestine at approximately 7.5 centimeters (about 3 inches). However, the actual diameter will vary by stage of peristalsis.

Aside from differences in diameter, the anatomical transition from the small intestine to the large intestine is easily identified. The large intestine is separated from the last section of the small intestine, the ileum (not to be confused with the bone of the hip, the ilium), by the ileocecal valve. This valve controls the downstream flow of intestinal contents from the small to large intestines. As the lumen of the ileum distends with content via upstream peristalsis, local pressure and sphincter relaxation open the valve to allow passage into the first segment of the large intestine, the ascending colon. The valve is a one-way system. If there is distention and increased pressure in the ascending colon, the valve prevents backflow primarily by reflexively increasing sphincter tension.

Cecum

The first segment of the large intestine is the cecum, a pouch-like structure from the level of or just above the ileocecal valve, downward about 6 centimeters (around 2.4 inches).

Appendix

Extending from the inferior aspect of the cecum is the appendix. It is approximately 8 to 10 centimeters (3 to 4 inches) in length and about 1.3 centimeters (0.5 inch) in diameter. While the appendix is often considered to be a vestige of a no-longer-present organ, its structure contributes to the accumulation and multiplication of intestinal bacteria.

Colon

Above the cecum, the large intestine transitions into the first segment of the colon, the ascending colon. After the approximately 20-centimeter (about 8 inches) ascension, the tube folds to the right (viewed from the anterior) to become the transverse colon. The transverse colon spans about 45 centimeters (roughly 18 inches) laterally across the abdomen, where the tube bends sharply downward. The ensuing 30 centimeters (about 12 inches) are vertically oriented and called the descending colon. As the tract descends past this point, there is a marked inward curve followed by a sharper downward curve termed the sigmoid colon (two curves make an “s”). This 45-centimeter (about 18 inch) segment moves the gastrointestinal tube from lateral to medial, anterior to the sacrum.

Rectum

After the gastrointestinal tube is redirected medially and oriented downward via the sigmoid colon, it transitions to become the rectum. The rectum is approximately 20 centimeters (about 8 inches) in length, the final 5 centimeters (2 inches) extending lower than the point of the coccyx. Along the length of the rectum, the tube’s diameter slightly expands, becoming a point of short-term and transient storage for feces before excretion. Its walls are more thickly muscled than the previous intestinal segment to effectively remove feces into the subsequent anal canal.

Anus

Immediately after the rectum, the anal canal passes through the perineum and terminates at the anus, the opening to the exterior. This short segment is about 3.8 to 5 centimeters (1.7 to 2 inches) in length and is enveloped by two layers of sphincter muscles:

Internal anal sphincter – the inner and more superior layer, comprised primarily of involuntary muscle

External anal sphincter – the outermost inferior layer, comprised primarily of skeletal muscle under voluntary control

The inner mucosal layer of the anal canal is heavily folded to form vertical longitudinal columns. This structure enables significant expansion and complete occlusion to facilitate the emptying of the gastrointestinal tube. Both sphincters are normally contracted to prevent passage. They are relaxed only during defecation.

Related Reading

- The Gastrointestinal System: An Introduction

- The Gastrointestinal System: The Mouth and Tongue

- The Gastrointestinal System: Anatomy of Taste

- The Gastrointestinal System: Swallowing

- The Gastrointestinal System: The Esophagus

- The Gastrointestinal System: Stomach Structure

- The Gastrointestinal System: Stomach Peristalsis

- The Gastrointestinal System: Small Intestine

- The Gastrointestinal System: The Pancreas