The stomach functions to temporarily store ingested food and drink, to more aggressively continue the chemical digestive processes begun in the oral cavity, and to mechanically break down that chemically degraded food.

As food enters the stomach, the musculature in the more superior (upper) segments of the stomach will relax to accommodate the incoming volume. Following stomach expansion, digestive fluids — up to three to four liters per day — are secreted from specialized cells in the fundus. The most important such liquids are hydrochloric acid and the enzymes pepsin and gastric lipase. Hydrochloric acid causes exposed food molecules to unfold and expose intramolecular bonds (peptide bonds). It also activates pepsin, whose enzymatic purpose is to chemically break down peptide-bond-laden proteins. Gastric lipase is responsible for about a third of the breakdown of ingested lipids (aka fats). The combined material made up of these fluids and the bolus is called chyme.

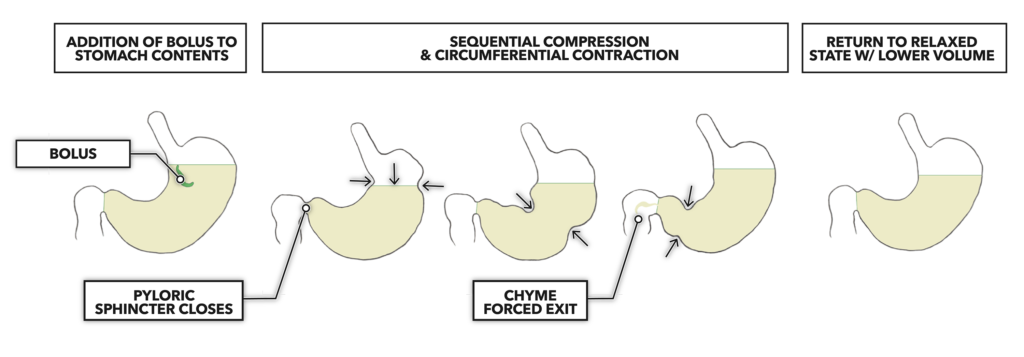

Whereas transit of the bolus was accomplished by simple peristalsis in the esophagus, the muscular contractions of the stomach are more complex. They must be both peristaltic in nature, moving ingested and partially digested food downstream and out of the stomach, and they must also produce contractile patterns that robustly mix and recycle the stomach contents.

Stomach muscle contractions are reflexive and coordinated. The longitudinal and oblique layers provide compressive force within the entire stomach and also create localized areas of stricture that facilitate mixing. The circumferential layer provides peristaltic drive. When triggered by increased volume and increased acidity, peristaltic and mixing waves of contractions occur about every 20 seconds. The strength of contractions increases as the wave nears the pylorus and, at the end of each wave, the pyloric sphincter lightly relaxes and allows a small amount of liquefied chyme to exit to the small intestines. The shape of the stomach paired with the contractile pattern pushes chyme that did not exit upwards to be recycled through mixing and peristaltic processes.

The rate of passage of foodstuffs through the stomach is dependent on food composition but generally occurs, bolus entry to chyme exit, in about two to four hours. Carbohydrates pass through most quickly. Proteins and lipids are processed more heavily in the stomach and are slower to pass. Although some substances, like water, are absorbed from the stomach, it acts primarily as a transformative conduit, preparing ingested foodstuff for more complete downstream digestive processes and later absorption.