When we consider the core, we have to realize it does not simply name a few abdominal and lumbar muscles. A bigger picture is required. And irrespective of definition and muscles included, if we think about the core requiring stabilization, we may wonder why it does, in fact, need to be stable.

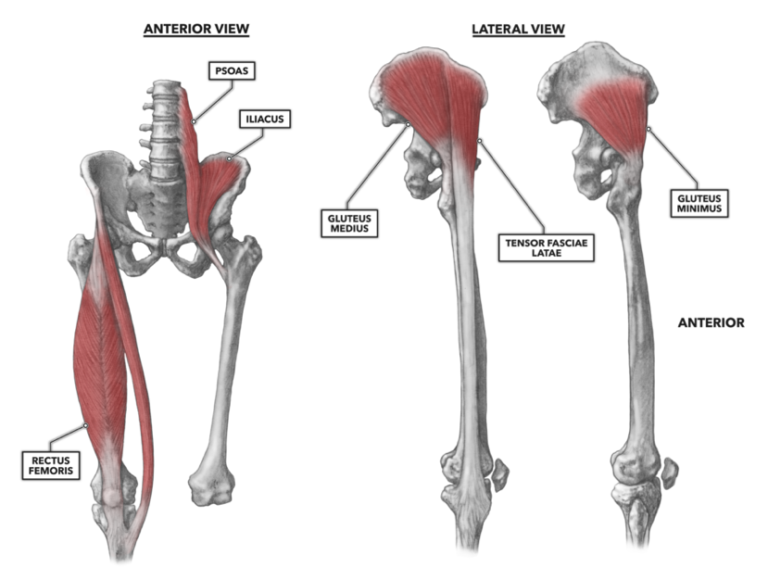

Very simply, the hips are part of and are the engines of the core. They produce power, and in order to apply that power usefully, the rest of the core has to be held stable. Anatomically, this means we need to add more muscles to the already large list of those related to the core — those that cross the hip:

So if the hips are part of the core and the hips are the primary generator of athletic power, then rigidity of the lever arms related to the hips is crucial to the transfer of that power. This is true of all our movements in the gym and in real life. When we jump, lift, run, punch, or throw, the hips produce the force, and maintaining or moving the entirety of the core under tight control is a prerequisite for proper movement execution. The easy example here is in the back squat: Without stability of the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae, and the interface of the vertebrae with the pelvis via the sacrum, force produced by the hips is dampened and performance is inhibited. Stabilization of the midline facilitates proper execution of the squat and better performance. You see this effect frequently in the gym. As soon as a trainee’s back begins to round as they come up out of the bottom, they lose drive and either have to grind and fight to complete the rep — or they fail.

Midline stability is not just about power generation. It can also specifically affect posture, and not every posture we assume occurs in an environment where forces are applied to the body longitudinally or symmetrically. The ability of our musculature to differentially contract against angular or asymmetric forces is crucial to maintaining core position.

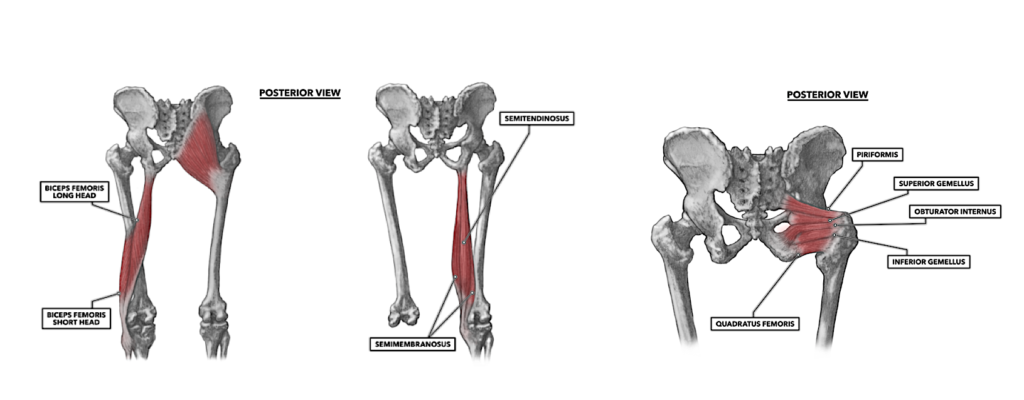

Figure 1: If part or all of the body is placed at an angle against gravity, the skeleton, which very efficiently reduces the muscular effort required to maintain posture when standing, needs significant muscular assistance to remain linear. To keep the body in line during a push-up or plank, muscles all along the body — ankle to head, anterior and posterior — isometrically contract. Weakness or lack of endurance on one side or the other induces sagging or rounding.

If we encounter a force that pushes the left shoulder back, our body’s innate reflex is to contract the left anterior and right posterior core musculature. The body attempts to maintain its postural position. We don’t even think about it. The stronger we are in that musculature, the more stable we are. This is a great reason to consider midline stabilization when training the general public, but this type of training is critical for the elderly. If an elderly person becomes unstable and falls, they have a high chance of permanent institutionalization, particularly if the hip is fractured in the fall.

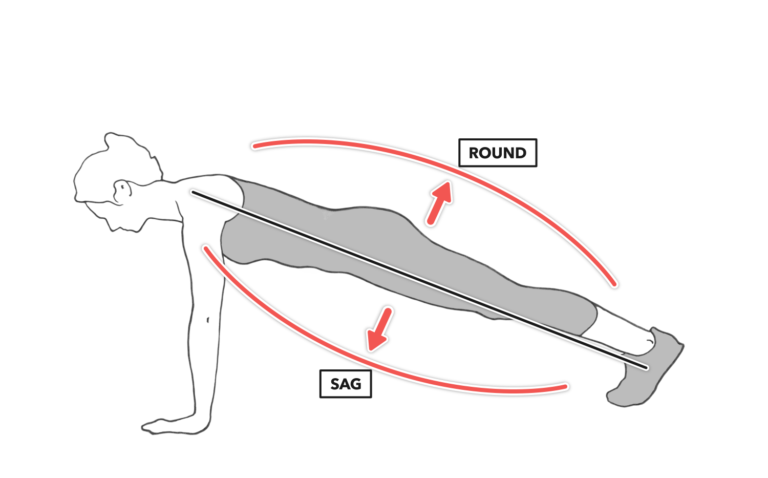

Figure 2: The anatomy of the core expands beyond the idea of flexion (anterior) and extension (posterior). It by necessity includes rotational stability: muscular resistance against destabilizing forces around the core axis.

A final observation about the core is that it can be a situational assemblage, affected by which part of the body is most stable. This means that which part of the body is connected to the earth affects which structures and muscles are maintaining midline integrity. When we invert the body, as in a handstand, the shoulders become the core of power production and the muscles that control the levers around that joint are now active parts of the core. So in practice, it is better to consider “midline stabilization” as the important training stimulus and performance outcome.

Midline stabilization is an objective and measurable concept — is the midline stable or wiggling? — that is easy to understand. The “core” on the other hand has multiple definitions, is subjectively and situationally variable, and is not easily measurable. The best use of the word “core” is as a teaching cue, as trainees recognize that word in describing the trunk of the body.