Research has repeatedly indicated obesity and the metabolic syndrome increase risk of infection, lead to poorer disease outcomes in response to infection, and reduce vaccine effectiveness (1). This 2016 paper reviews multiple mechanisms by which metabolic defects could contribute to immune system impairment.

The immune system consists of two systems that work in concert to coordinate disease response. The innate immune system, which includes monocytes and macrophages, provides a rapid, nonspecific response to potential threats via an inflammatory response (2). The adaptive immune system, which consists of B and T cells, supports immunological memory and allows the body to respond more effectively to repeated infections (3). Immune system defects can lead to an insufficient or excessive immune response, either of which can be harmful (4, 5).

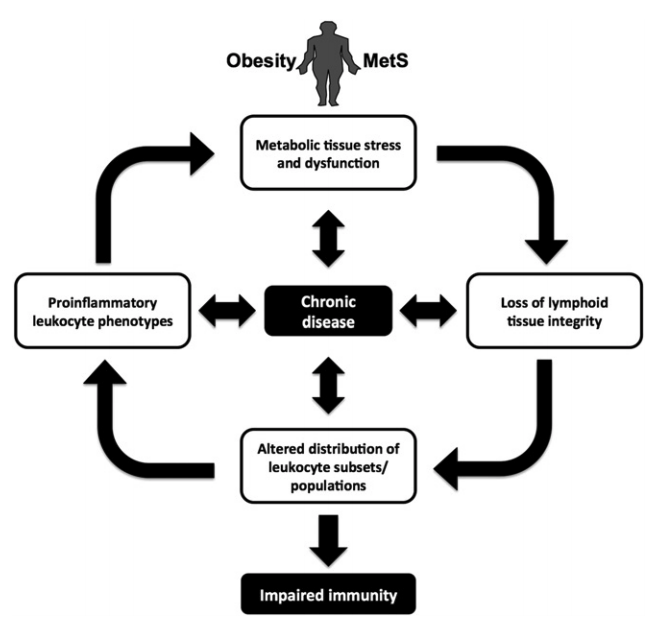

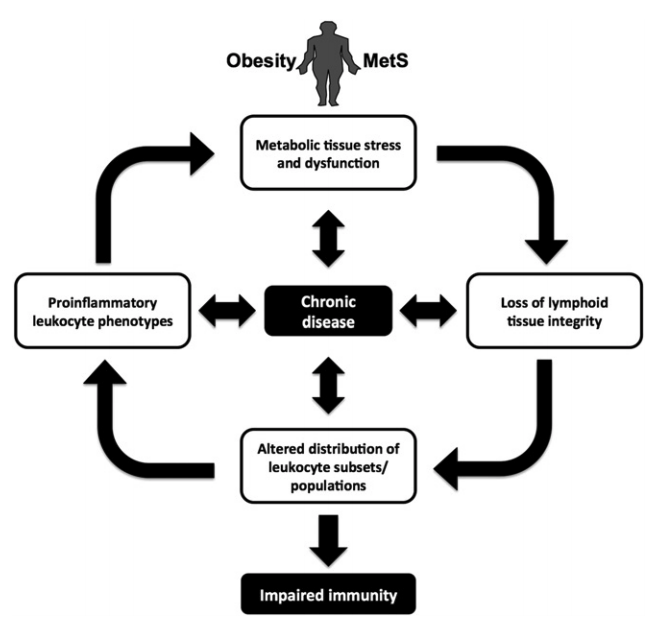

Increased adipose tissue volume, as is seen with obesity, leads to increased inflammation, both directly and indirectly. Adipose tissue expands in adult humans primarily through hypertrophy (i.e., increasing the size of fat cells) rather than hyperplasia (i.e., generation of new fat cells). As adipose cells expand, various cellular responses lead to increased levels of inflammation within fat tissue (6). Inflammation is followed by leukocyte infiltration, with the share of white blood cells present in adipose tissue rising from 5% in healthy tissue to 50% in obese individuals (7). This inflamed, leukocyte-rich adipose tissue secretes other inflammatory compounds such as TNF-a and IL-6 (8). These same compounds may make insulin resistance — which led the adipose tissue to expand in the first place — worse as increased TNF-a inhibits glucose uptake within skeletal muscle cells (9). In other words, the inflammatory response to adipose tissue expansion (fattening) leads to further worsening of insulin resistance.

As the fat tissue expands and becomes insulin-resistant, additional fat is released into circulation, some of which is taken up by organs (10). Immune system organs — including the bone marrow, thymus, and spleen — can take on fat through this process, which is much like the gradual immune system organ fat accumulation associated with aging (11). Fat accumulation impairs organ function and thereby impairs the production, functionality, and integrity of developing immune cells (12).

Figure 1: Summary of the mechanisms by which obesity, metabolic syndrome, impaired immune function, and chronic disease interact

One specific effect of these impairments is a reduction in the variety of circulating T-cells. This then leads to a reduction in the variety of pathogens to which the body can provide an effective immune response (13). Obese individuals, for example, show a reduced T-cell response to influenza virus infection and fail to maintain memory T-cells after infection. For similar reasons, vaccine failure rates are higher among obese individuals for the hepatitis B, tetanus, and flu vaccines (14). Across these and other conditions, obese individuals are more likely to have complications related to infectious disease and to require hospitalization (15).

The association between fat accumulation within immune organs and impaired immune function may explain the decline in immunity associated with aging. It may also explain the immune system benefits associated with fasting, caloric restriction, and similar dietary interventions (16).

Additionally, metabolic syndrome may impair immune function via secondary effects on HDL cholesterol. A growing body of research indicates HDL cholesterol plays a role in immune function and may help manage the inflammatory (innate) response to infection (17). Obesity and insulin resistance are associated with lower levels of HDL cholesterol and so may impair this element of the immune response. These and other mechanisms may also explain the increased rates of allergies (18) and cancer (19) in obese and metabolically unhealthy individuals, given the role immune system function plays in these conditions.