This 2018 review combines a comprehensive summary of brain aging with a brief overview of the evidence linking metabolic patterns to acceleration or suppression of brain pathology.

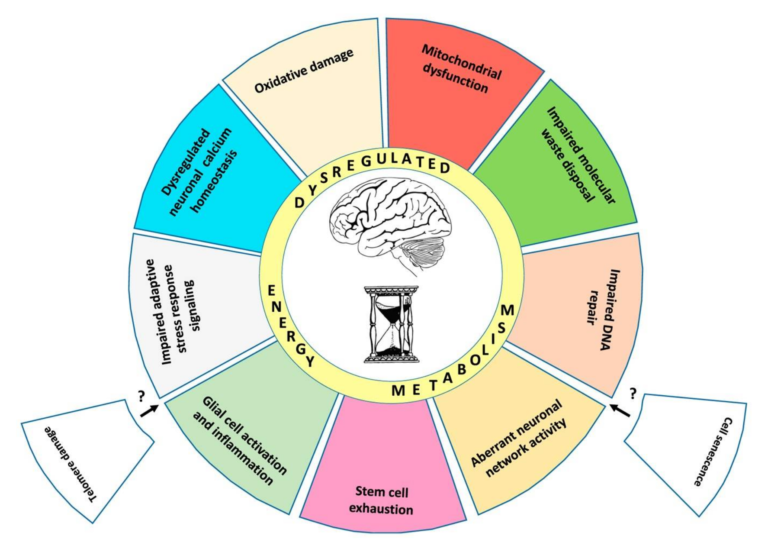

The authors outline 10 “established hallmarks” of brain aging, presented in Figure 1 below.

Briefly:

- Mitochondrial dysfunction – Mitochondria generate the ATP required for neuronal function, maintenance, and repair while also supporting various signaling pathways. Aging is associated with structural and functional defects in the mitochondria, including membrane breakdown and impaired electron transport chain function (1).

- Oxidative damage – Aging leads to the progressive damage of brain proteins when generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) exceeds what can be cleared by antioxidant defenses. Animal studies have shown that impairments in oxidative defense mechanisms alone can trigger the symptoms of brain aging (2).

- Impaired lysosome and proteasome function – Neurons, unlike most cells, generally do not replicate; instead, they maintain function by removing and replacing damaged molecules. Lysosomes and proteasomes manage this process; animal research indicates the activity of these systems is diminished in the aging brain, and pharmaceutical upregulation of these same functions can reverse neurodegeneration (3).

- Dysregulation of neuronal calcium homeostasis – Calcium ions support the function and adaptation of the neuronal network, and calcium dysregulation is seen in aging brains. A small number of rat studies have indicated restoration of normal calcium levels ameliorates cognitive deficits (4).

- Compromised adaptive cellular responses – Neuronal pathways for responding to stress and activating cellular defense mechanisms, many of which are triggered by changes in ATP and reactive oxygen species levels, are impaired in aging, increasing stress vulnerability (5).

- Aberrant neuronal network activity – Aging is associated with decreased neural network function and structural integrity. The function of the default mode network (DMN), which represents the function of the brain in the absence of deliberate activity, is particularly disordered in the aging and cognitively impaired (6).

- Impaired DNA repair – DNA is continually damaged and repaired as a consequence of normal cellular function, with increases in this damage occurring after synaptic activity. Decreased DNA repair protein activity is seen in older mice, and multiple premature aging syndromes (Cockaye syndrome, Werner syndrome, and ataxia telangiectasia) are caused by mutations in DNA repair processes (7).

- Inflammation – Inflammation levels are increased both in the aging brain and in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease and stroke. Rat studies have shown inhibition of inflammatory cascades mitigate Alzheimer’s and stroke-related damage (8).

- Impaired neurogenesis – While most neurons are produced early in life, areas of the hippocampus and olfactory bulb continue to produce new neurons from stem cells in the adult brain. Reductions in this neurogenesis are a normal consequence of aging and may contribute to associated cognitive impairment (9).

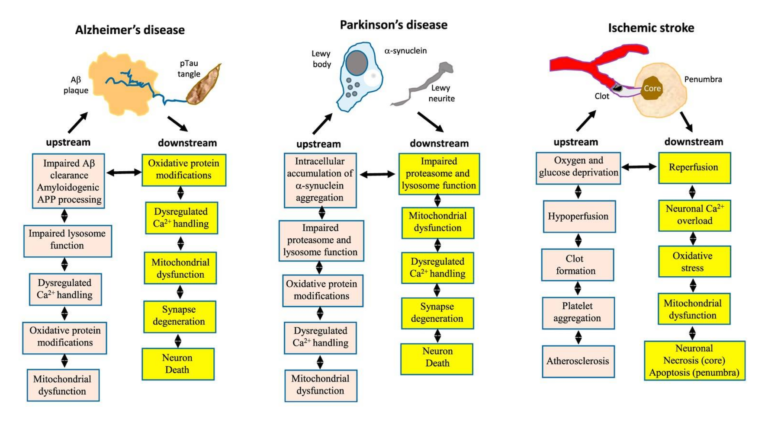

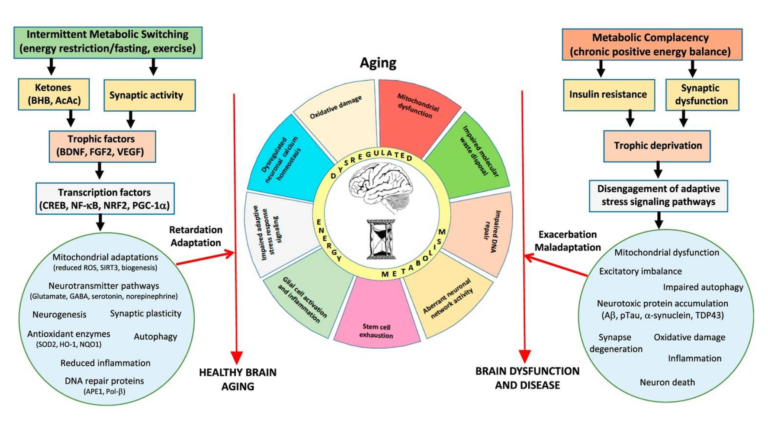

Alterations in brain metabolism are a well-known element of neurodegenerative diseases, with deficiencies in glucose metabolism appearing early in the development of Alzheimer’s, prior to other symptoms (10). Parkinson’s patients similarly show reduced glucose metabolism in areas associated with motor control (11). Insulin resistance is associated with loss of cognitive function, and decreased glucose consumption/metabolism is seen in the temporal and parietal lobes of elderly subjects with cognitive impairment (12). This leads the review authors to argue metabolic defects may play a role in the causation and/or development of neurodegenerative disease, as summarized in Figures 3 and 4, below.

Figure 3: The hallmarks of brain aging likely contribute to or increase neuronal susceptibility to the physiological defects associated with Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and stroke.

-

Figure 4: Intermittent depletion of liver glycogen stores and mobilization of fatty acids activate pathways that resist or reverse the consequences of aging, including “mitochondrial biogenesis and stress resistance; adaptive modifications of neurotransmitter signaling pathways; upregulation of autophagy, antioxidant defenses, and DNA repair; stimulation of neurogenesis; and suppression of inflammation.” Chronic positive energy balance, conversely, contributes to these same hallmarks and thus to aging, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and stroke.

For example, amyloid beta plaques are widely implicated as the cause of Alzheimer’s disease, but there are both significant elderly populations that have high amyloid levels but do not have Alzheimer’s and populations that have low amyloid levels and do suffer from the disease (13). The review authors argue amyloid accumulation may be a natural consequence of aging, and the hallmarks of aging outlined above create neuronal cells that are susceptible to amyloid-based damage. Similar mechanisms may link Parkinson’s and stroke to these same pathologies (14).

Poor metabolic health has been linked to poor cognitive performance, reduced gray matter, and reduced white matter integrity (15). Higher BMI is associated with reduced cerebral glucose utilization (16). In mice, insulin resistance is associated with increased brain inflammation, oxidative damage, poor calcium regulation, impaired learning and memory, and increased stress vulnerability (17).

Conversely, both exercise and intermittent energy restriction have been linked to improvements in mental and motor performance and robustness against neurodegenerative disease (18). As shown in Figure 4, the authors hypothesize these intermittent metabolic stressors upregulate cellular clearance and repair measures such as autophagy, DNA repair, and stress resistance and clearance; subsequent refeeding leads to protein production, cellular growth, and restoration (19). This is similar to the “metabolic switch” theory previously discussed on CrossFit.com and indicates intermittent bioenergetic challenges — challenges such as extended exercise or intermittent fasting, which lead to clearance of liver glycogen stores and a temporary reliance on circulating fats as a primary fuel source — repair and support resistance to the factors leading to brain aging and neurodegenerative disease.

Takeaway: Poor metabolic health can be linked, directly or indirectly, to the majority of the biological factors associated with brain aging and neurodegenerative disease. Mechanistic understanding and animal models suggest fasting and/or exercise can slow or reverse the progression of brain aging and disease.