Question: Obesity has been linked to increased prevalence of age-related diseases, including arthritis and dementia. How does obesity contribute to these conditions?

Takeaway: Increased adipose tissue mass leads to chronic, systemic inflammation, which contributes to these conditions. The inflammatory response of adipose tissue may explain the relationship between obesity and a variety of conditions.

The risk of a variety of inflammation-associated conditions — including heart disease, arthritis, and dementia — increases with age; concomitant obesity increases these risks further (1). This 2017 review summarizes mechanisms by which obesity may contribute to the progression of these conditions.

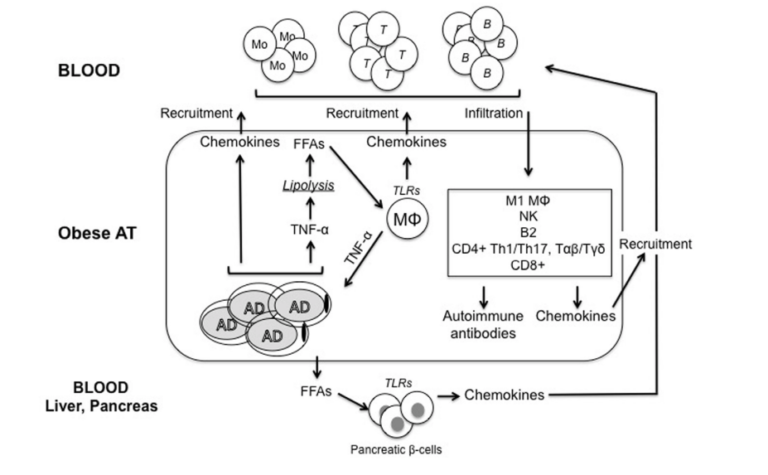

As fat mass increases, the cells of the adipose tissue (fat tissue) expand. Adipose tissue hypertrophy leads to a local inflammatory state and later release of cytokines and adipokines into circulation. This process is briefly summarized in the figure below. Hypertrophic adipose tissue releases TNF-a into circulation. As the fat cells continue to expand, areas become hypoxic (i.e., deprived of oxygen and nutrients), which further increases cellular stress and cytokine release. Over time, this expanded adipose tissue will be infiltrated by immune cells, which stimulate yet further release of cytokines and chemokines (2). Elevated cytokine levels then contribute to insulin resistance, exacerbating an inflammatory state that impairs the responsiveness of other insulin-sensitive tissues such as the muscle, liver, and pancreas (3). Simultaneously, fatty acid release into the bloodstream is increased in inflamed adipose tissue, further heightening insulin resistance by contributing to lipid accumulation in these same insulin-sensitive tissues (4). Over time, insulin resistance impairs the ability of the pancreas to moderate blood glucose levels by releasing insulin (5). The pancreas responds by increasing pancreatic cell mass and insulin release, which stresses the beta cells over time and eventually leads to beta cell failure (6). Through these mechanisms, increased adiposity (i.e., fattening) directly contributes to insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, inflammation, and the variety of diabetic comorbidities that follow from these factors (7).

Figure 1: Adipocytes (AD) secrete inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which lead to immune cell infiltration, which further increases inflammatory release. Simultaneously, inflamed adipose tissue releases free fatty acids into circulation, contributing to insulin resistance in insulin-sensitive tissues, including the pancreas. Over time, these and other downstream effects contribute to insulin resistance in fat and other tissues, a systemic inflammatory state, and damage to organs and other systems associated with poor metabolic health.

The authors of this review provide two specific examples: arthritis and dementia. Obese patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have poorer therapeutic responses to treatment and generally a more severe condition than RA patients who are not obese (8). The relationship between obesity and RA may be underappreciated given the cachexia associated with RA; RA patients often have lower lean body mass than their peers and therefore may be more obese at the same BMI (9). RA is known to be an inflammatory disease, so the adipose-tissue-mediated inflammatory state described above contributes to its development and progression; adipokines (cytokines secreted directly from adipose tissue, including leptin and adiponectin) have further been directly linked to RA progression and RA-related tissue damage (10). Osteoarthritis (OA) is similarly correlated with obesity due to mechanisms that may be related to obesity-mediated reductions in activity levels and inflammation-mediated impairments to tissue regeneration and repair (11).

Finally, the authors note preliminary evidence suggests adipokines, which can cross the blood-brain barrier, may explain the link between metabolic disease and increased risk of dementia (12).

The paper outlines multiple mechanisms by which obesity, via its downstream effects on insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and inflammation, can contribute to conditions associated with metabolic disease and diabetes. These arguments suggest tools to moderate obesity and reduce obesity-related inflammation may prevent or reduce the severity of these comorbidities.

Notes

- Body mass index influences the response to infliximab in ankylosing spondylitis; Overweight decreases the chance of achieving good response and low disease activity in early rheumatoid arthritis; The obesity epidemic and consequences for rheumatoid arthritis care; Inflammaging decreases adaptive and innate immune responses in mice and humans

- Importance of TNFalpha and neutral lipases in human adipose tissue lipolysis; Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibits signaling from the insulin receptor; Chronic TNFalpha and cAMP pre-treatment of human adipocytes alter HSL, ATGL and perilipin to regulate basal and stimulated lipolysis; A ceramide-centric view of insulin resistance; CD8+ effector T cells contribute to macrophage recruitment and adipose tissue inflammation in obesity; Depot-specific differences in inflammatory mediators and a role for NK cells and IFN-gamma in inflammation in human adipose tissue; Adipose tissue dendritic cells enhances inflammation by prompting the generation of Th17 cells; Reduced adipose tissue oxygenation in human obesity: Evidence for rarefaction, macrophage chemotaxis, and inflammation without an angiogenic response; Adipose tissue hypoxia, inflammation, and fibrosis in obese insulin-sensitive and obese insulin-resistant subjects; Hypoxia-inducible factors as essential regulators of inflammation; Healthy ageing in 2016: Obesity in geroscience – is cellular senescence the culprit?; A role for the NLRP3 inflammasome in metabolic diseases – did Warburg miss inflammation?; Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling; Upregulated NLRP3 inflammasome activation in patients with type 2 diabetes

- Inflammation, metaflammation and immunometabolic disorders; Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue; Normalization of obesity-associated insulin resistance through immunotherapy; B cells promote insulin resistance through modulation of T cells and production of pathogenic IgG antibodies; Adipose tissue as an immunological organ; Adipose type one innate lymphoid cells regulate macrophage homeostasis through targeted cytotoxicity

- Ibid.

- Insulin sensitivity: Modulation by nutrients and inflammation

- Five stages of evolving beta-cell dysfunction during progression to diabetes

- Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications; Inflammation and insulin resistance

- Obesity in rheumatoid arthritis; Impact of obesity on the clinical outcome of rheumatologic patients in biotherapy; Rheumatoid arthritis: Obesity impairs efficacy of anti-TNF therapy in patients with RA; Body mass does not impact the clinical response to intravenous abatacept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Analysis from the “pan-European registry collaboration for abatacept (PANABA); Association between body composition and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. A systematic review; Impact of obesity on remission and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Rheumatoid cachexia: Depletion of lean body mass in rheumatoid arthritis. Possible association with tumor necrosis factor; Rheumatoid cachexia: A clinical perspective; Rheumatoid cachexia: A complication of rheumatoid arthritis moves into the 21st century

- Rheumatic diseases and obesity: adipocytokines as potential comorbidity biomarkers for cardiovascular diseases; Biomolecular features of inflammation in obese rheumatoid arthritis patients: Management considerations

- Aging and osteoarthritis: An inevitable encounter?; Cellular senescence in aging and osteoarthritis; Arthritis-specific health beliefs related to aging among older male patients with knee and/or hip osteoarthritis; Aging and age related stresses: A senescence mechanism of intervertebral disc degeneration; Aging and osteoarthritis; Aging processes and the development of osteoarthritis; The role of aging in the development of osteoarthritis; The effect of aging and mechanical loading on the metabolism of articular cartilage; Aging and osteoarthritis: Central role of the extracellular matrix

- Global epidemiology of dementia: Alzheimer’s and vascular types; Global prevalence of dementia: A Delphi consensus study; Modifiable risk factors for prevention of dementia in midlife, late life and the oldest-old: validation of the libra index; The path from obesity and hypertension to dementia; Obesity and vascular risk factors at midlife and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease; Adipokines: A link between obesity and dementia?; Obesity and dementia: Adipokines interact with the brain

Comments on Aging, Obesity and Inflammatory Age-Related Diseases

There was an article posted here a few months ago which used the term “overfat”. There was some objection to introducing a new term such as this, but I’m starting to like it. One thing today’s article mentions is that rheumatoid arthritis often occurs in people who do not have a high body mass index (BMI), but are still considered obese. They are obese in the sense that they carry a lot of fat, but low BMI because they carry very little muscle. This situation of low muscle mass and high fat mass is the worst of both worlds.

Muscle mass has been shown to be predictive of longevity independent of "either traditional cardiovascular risk factors (dyslipidemia, hypertension, and inflammation) or glucose dysregulation (pre diabetes, diabetes, insulin resistance, and dysglycemia).” Muscle mass is an important metabolic regulator and is also the largest repository of amino acids in the body. This paper “The Underappreciated Role of Muscle in Health and Disease” provides a few interesting nuggets. For example, death by starvation happens when muscle tissue is depleted. And survival from acute illness or injury is reduced. People with low muscle mass are less likely to survive severe burns and less likely to ever walk again following a hip fracture in old age.

So, high body fat gives you all of the inflammatory problems mentioned in today’s article (rheumatoid arthritis dementia), while low muscle is a second independent predictor of longevity. One thing made clear by this and other recent articles is that adipose tissue is not just a fuel tank for lipids. In obese people, it is home to a large number of macrophages (up to 50% of total adipose weight), which promote a pro-inflammatory state. Building muscle and losing fat shouldn’t be seen as a vain endeavor*, but one critical to health.

*Unless the pursuit of body composition takes over your life.

M1 macrophages, that is. M1 are the pro-inflammatory guys, whereas M2 (alternatively-activated macrophages) are immune calming. We are starting to learn a lot more about the inflammatory component of obesity. See here for more:

Thank you, Chris. It's a really interesting paper. The graphic on p.4 is quite instructive. A few doctors have warned against long-duration fasting during the pandemic and this would support their concern.

So, in addition to greater macrophage infiltration, the macrophages in obese adipose tissue are of a pro-inflammatory phenotype (M1). That's truly an unfortunate situation.

Traduction rapide

Vieillissement, Obésité et Maladies liées à l’inflammation

Question : L’obésité a été liée à une augmentation des maladies liées au vieillissement, qui incluent l’arthrite et la démence. Comment est-ce que l’obésité contribue à ces conditions ?

Conclusion Rapide : L’augmentation des tissus adipeux mènent à l’inflammation chronique et systémique ce qui contribue à ces conditions.La réponse inflammatoire des tissus adipeux pourrait expliquer la relation entre l’obésité et ces conditions

Augmentation de la masse grasse = Expansion du tissu adipeux

Hypertrophie du tissu adipeux = état inflammatoire local et sécrétion de cytokine et adipokine dans le sang.

Expansion de la cellule de gras = Zones aux alentours en hypoxie (plus d’oxygène et de nutriments) ce qui augmente le stress cellulaire.

Ces cellules sont ensuite infiltrées par des cellules immunitaires qui stimulent encore plus les marqueurs inflammatoires.

La cytokine élevée contribue à la résistance à l’insuline ce qui exacerbe l’état inflammatoire et élimine la sensibilité à l’insuline de tissus comme les muscles, le foi et le pancréas.

Simultanément, l’acide gras sécrété dans le sang est augmenté dans le tissu adipeux enflammé ce qui élève encore plus la résistance à l’insuline.

A travers le temps, la résistance à l’insuline empêche la capacité du pancréas de modérer le glucose dans le sang en sécrétant de l’insuline.

Le pancréas répond à cela en augmentant la masse des cellules pancréatiques et en sécrétant encore plus d’insuline.

A travers ces mécanismes, grossir contribue directement à la résistance à l’insuline, l’hyperglycémie, l’inflammation et une variété de comorbidités diabétiques.

Aging, Obesity and Inflammatory Age-Related Diseases

4