The risk of a variety of inflammation-associated conditions — including heart disease, arthritis, and dementia — increases with age; concomitant obesity increases these risks further (1). This 2017 review summarizes mechanisms by which obesity may contribute to the progression of these conditions.

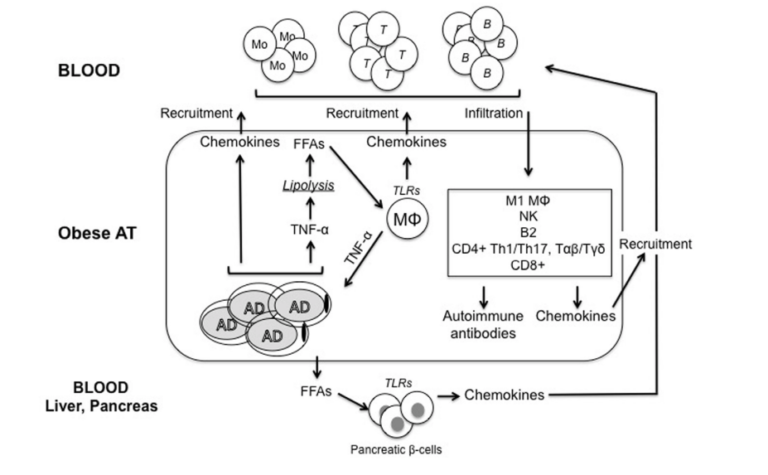

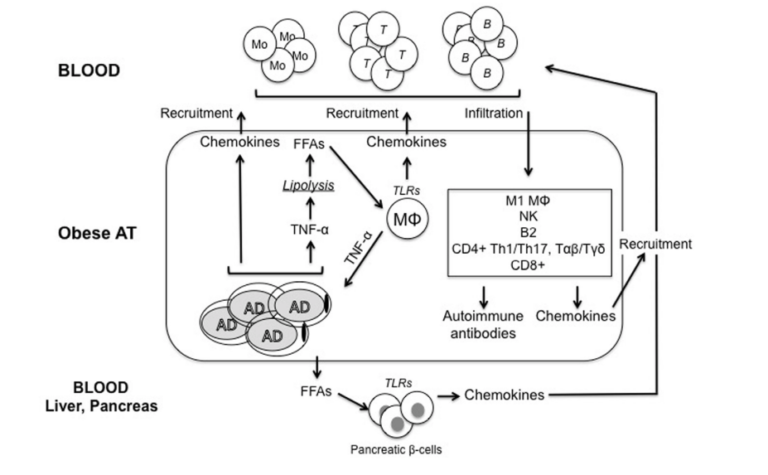

As fat mass increases, the cells of the adipose tissue (fat tissue) expand. Adipose tissue hypertrophy leads to a local inflammatory state and later release of cytokines and adipokines into circulation. This process is briefly summarized in the figure below. Hypertrophic adipose tissue releases TNF-a into circulation. As the fat cells continue to expand, areas become hypoxic (i.e., deprived of oxygen and nutrients), which further increases cellular stress and cytokine release. Over time, this expanded adipose tissue will be infiltrated by immune cells, which stimulate yet further release of cytokines and chemokines (2). Elevated cytokine levels then contribute to insulin resistance, exacerbating an inflammatory state that impairs the responsiveness of other insulin-sensitive tissues such as the muscle, liver, and pancreas (3). Simultaneously, fatty acid release into the bloodstream is increased in inflamed adipose tissue, further heightening insulin resistance by contributing to lipid accumulation in these same insulin-sensitive tissues (4). Over time, insulin resistance impairs the ability of the pancreas to moderate blood glucose levels by releasing insulin (5). The pancreas responds by increasing pancreatic cell mass and insulin release, which stresses the beta cells over time and eventually leads to beta cell failure (6). Through these mechanisms, increased adiposity (i.e., fattening) directly contributes to insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, inflammation, and the variety of diabetic comorbidities that follow from these factors (7).

Figure 1: Adipocytes (AD) secrete inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which lead to immune cell infiltration, which further increases inflammatory release. Simultaneously, inflamed adipose tissue releases free fatty acids into circulation, contributing to insulin resistance in insulin-sensitive tissues, including the pancreas. Over time, these and other downstream effects contribute to insulin resistance in fat and other tissues, a systemic inflammatory state, and damage to organs and other systems associated with poor metabolic health.

The authors of this review provide two specific examples: arthritis and dementia. Obese patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have poorer therapeutic responses to treatment and generally a more severe condition than RA patients who are not obese (8). The relationship between obesity and RA may be underappreciated given the cachexia associated with RA; RA patients often have lower lean body mass than their peers and therefore may be more obese at the same BMI (9). RA is known to be an inflammatory disease, so the adipose-tissue-mediated inflammatory state described above contributes to its development and progression; adipokines (cytokines secreted directly from adipose tissue, including leptin and adiponectin) have further been directly linked to RA progression and RA-related tissue damage (10). Osteoarthritis (OA) is similarly correlated with obesity due to mechanisms that may be related to obesity-mediated reductions in activity levels and inflammation-mediated impairments to tissue regeneration and repair (11).

Finally, the authors note preliminary evidence suggests adipokines, which can cross the blood-brain barrier, may explain the link between metabolic disease and increased risk of dementia (12).

The paper outlines multiple mechanisms by which obesity, via its downstream effects on insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and inflammation, can contribute to conditions associated with metabolic disease and diabetes. These arguments suggest tools to moderate obesity and reduce obesity-related inflammation may prevent or reduce the severity of these comorbidities.