This 2005 review argues an exercise-induced increase in IL-6 reduces the harmful effects of inflammation and the anti-inflammatory properties of exercise may explain the link between activity and health.

Low-grade, chronic inflammation (i.e., increased systemic levels of C-reactive protein, or CRP, and some cytokines) is associated with a variety of metabolic conditions, including the metabolic syndrome, Type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (1). Elevated levels of TNF and CRP have more specifically been associated with aging, diabetes, insulin resistance, and general and cause-specific mortality (2). Some of this same research has argued these associations point to a causal link and these same metabolic conditions may be exacerbated or outright caused by inflammation. TNF, specifically, has been found to directly inhibit insulin signaling and increase insulin resistance (3).

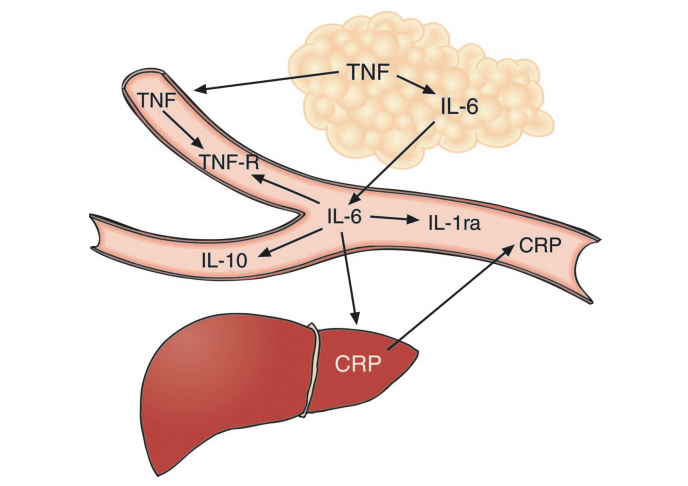

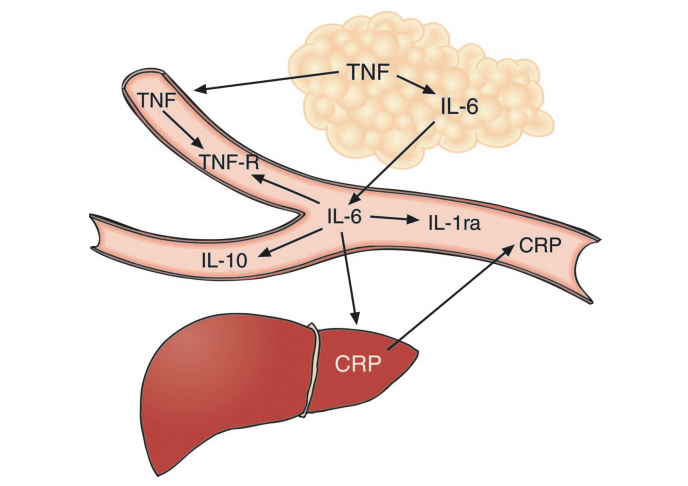

Figure 1: The authors illustrate the relationship between various cytokines. Increased TNF, derived from adipose tissue, leads to increased levels of IL-6 and other cytokines.

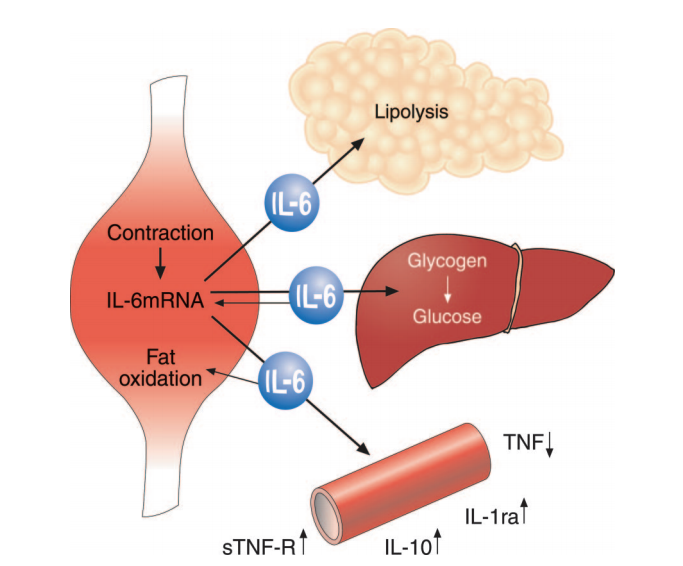

Individuals with chronic inflammation often have elevated IL-6 levels, which has led many to conclude IL-6 is a contributor to these same conditions. However, the authors of this review argue IL-6 is merely downstream of TNF and is itself primarily anti-inflammatory in its actions. As shown in the figure below, elevated TNF levels — which are primarily derived from adipose tissue (4) and so are a consequence of increased adiposity — lead to increased IL-6 production. Direct studies of IL-6, however, have consistently shown benefits favoring metabolic health. Rodent, human, and in vitro studies suggest IL-6 enhances lipolysis and increases fat oxidation (5). Genomic studies have found individuals with increased production of TNF and reduced production of IL-6 have an increased risk of diabetes and the metabolic syndrome, suggesting differential roles for TNF and IL-6 (6). This preliminary evidence indicates IL-6 may be beneficial; it may only be present at high levels in metabolically unhealthy individuals because it is downstream of TNF.

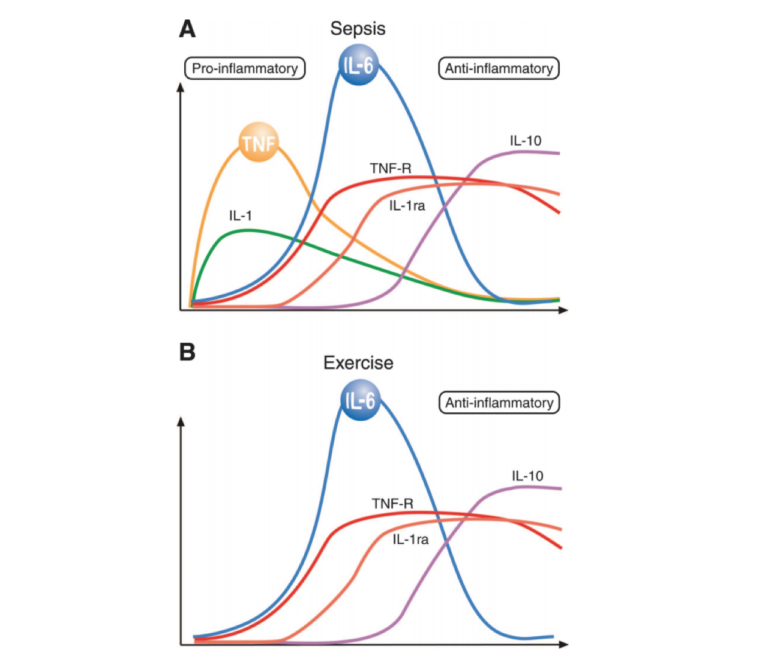

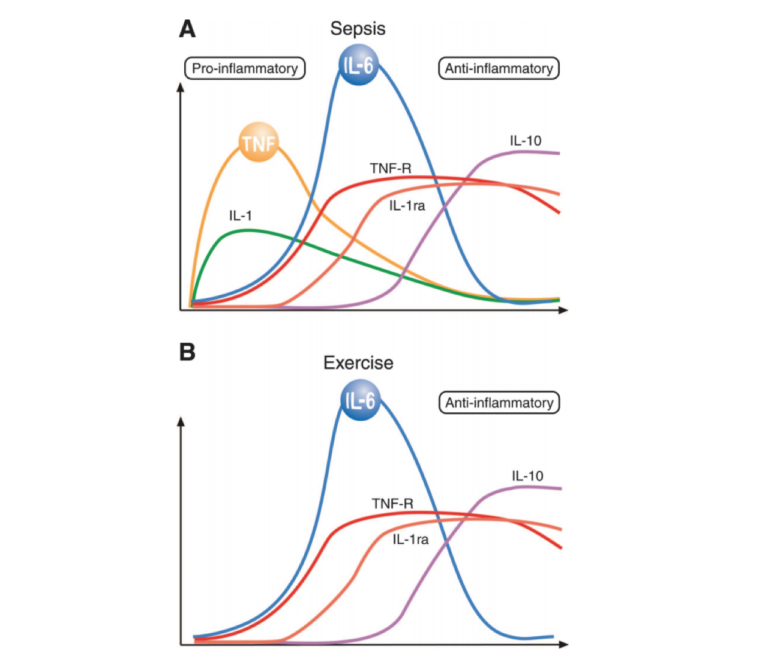

Exercise leads to a selective cytokine response. As shown in the figure below, and in direct contrast to the broad inflammatory response associated with sepsis (the classical model of inflammation), the distinguishing cytokine response to exercise is a rapid, dramatic (100-fold) increase in IL-6 followed by smaller elevations in other cytokines downstream of IL-6 (7). As the review authors note, the finding that exercise elevates IL-6 levels without muscle damage is “remarkably consistent” throughout the literature. Intensity, duration, muscle mass recruitment, and training level do seem to moderate IL-6 response (8). Carbohydrate suppresses the exercise-induced IL-6 response, and low muscular glycogen levels increase the response (9). These elevated IL-6 levels — when generated in the context of exercise, without an adipose-derived elevation in TNF levels — inhibit TNF production and reduce TNF levels, as shown in multiple in vitro and mouse studies (10).

Figure 2: A comparison of the cytokine responses of sepsis and exercise. Exercise does not lead to a significant elevation of TNF; instead, the distinguishing response is a dramatic increase in IL-6 followed by increases in other cytokines downstream of IL-6.

These authors have demonstrated the exercise-induced elevation in IL-6 suppresses TNF activity. In a previous paper (11), subjects were injected with a low dose of E. coli toxin at rest or during exercise. As expected, the toxin led to a two- to three-fold increase in TNF levels in resting subjects; in exercising subjects, however, the TNF response was entirely blunted. Mouse models that overproduce TNF are normalized via exercise (12). Elevated epinephrine levels during exercise may further suppress TNF, though the mechanism of these effects is not yet clear (13).

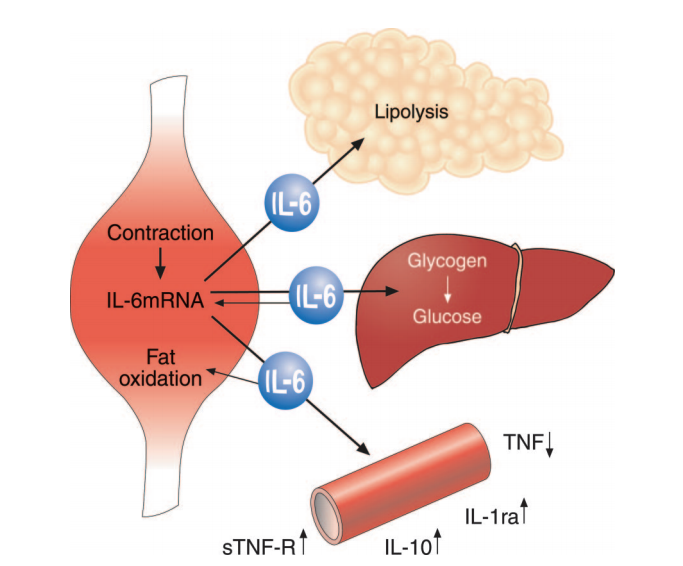

Figure 3: Muscular contraction increases IL-6 production, which stimulates lipolysis, supports glucose regulation during exercise, and suppresses production of pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF.

Taken together, these observations lead the authors to conclude exercise-induced IL-6 elevation produces an anti-inflammatory state by inhibiting production of TNF. These elevated IL-6 levels will simultaneously stimulate lipolysis and fat oxidation, reducing the excess adiposity that contributes to TNF overproduction. The authors argue IL-6 and other cytokines produced as a result of muscular exertion — which they collectively term “myokines” — may thus explain the relationships between increased levels of activity and metabolic health, increased activity and reduced inflammation, and sedentary behavior and metabolic disease (14). Further research could explore how the acute IL-6 response induced by exercise affects chronic inflammation levels and how different exercise programs specifically affect the chronic inflammatory state.