For decades, the war on heart disease had a simple villain: cholesterol. The marching orders were clear: fear saturated fat, keep your cholesterol low, and take the statin medication your doctor prescribes. It’s a narrative repeated so often that it’s perceived as truth: a fundamental rule of modern health where greasy foods clog your arteries, and a high cholesterol number is a direct threat to your life.

But what if this simple story has some significant plot holes? A growing body of scientific evidence and a chorus of skeptical researchers suggest that much of what we accept as fact is being re-examined. From the very definition of the “villain” to the effectiveness of our most prescribed drugs, the foundational pillars of the diet-heart hypothesis are showing signs of cracking. In Part 1, we examined the history of heart disease and its competing hypotheses. In Part 2, we took a deep dive into the many roles of Cholesterol itself. Here in Part 3, we’ll look at the world’s number one selling category of prescription drugs: statins.

Statins

The pitch is compelling: take a statin, lower your LDL-C, and you reduce your risk of dying from cardiovascular disease. But does the data support that promise? And what exactly are the costs?

To say the science of statins is controversial is a massive understatement. Some players are so enthusiastic about the benefits of statins that they think we should put them in the drinking water. Others are so pessimistic about the benefits and horrified by the risks, they’re publishing books with no-nonsense titles like “A Statin Free Life” and even more direct, “Fat and Cholesterol Do Not Cause Heart Attacks and Statins Are Not the Solution.” Each side views the other as a bad actor. One is framed as industry shills with no morals, on the take from big pharma, while the other is portrayed as crack-pot conspiracy theorists, “statin deniers,” putting millions of lives at risk.

It’s messy out there, but let’s try to unpack it.

The Discovery of Statins

Working from the framework of Ancel Keys’ lipid hypothesis and the idea that cholesterol in the blood causes heart disease, the story of statin discovery begins in the 1970s with a Japanese biochemist named Akira Endo. While working for the pharmaceutical company Sankyo, Endo screened thousands of fungal compounds in search of a substance that could inhibit the body’s internal cholesterol synthesis. He eventually isolated a compound called mevastatin (compactin) from the mold Penicillium citrinum. This discovery laid the groundwork for the development of more potent statins, including lovastatin, the first to be approved for clinical use by the FDA in 1987. Endo’s work launched a new era in cardiovascular pharmacology, one that would reshape both the treatment of heart disease and the pharmaceutical industry itself.

How Statins Work

Statins work by inhibiting an enzyme in the liver called HMG-CoA reductase, which plays a central role in a series of biochemical reactions in the body known as the mevalonate pathway. One outcome of this pathway is the creation of cholesterol. By blocking this enzyme, statins reduce the production of cholesterol, particularly within the liver, where much of the body’s cholesterol is made.

A Global Best-Seller

Statins are now the most widely prescribed class of drugs in the world. Since their debut in the late 1980s, statins have been marketed as revolutionary in the battle against heart disease. These drugs are designed to lower LDL cholesterol levels (specifically the cholesterol contained inside low-density lipoprotein particles, discussed in Part 2), thereby reducing the risk of heart attacks and strokes.

They go by names like Atorvastatin (Lipitor), Rosuvastatin (Crestor), Simvastatin (Zocor), Pravastatin (Pravachol), and Lovastatin (Mevacor, Altoprev).

The pharmaceutical industry has profited massively from this approach. Lipitor (atorvastatin) alone has generated more than $150 billion in sales for Pfizer Inc., making it the best-selling drug in history. Statins dominate prescription charts globally, with tens of millions of people taking them daily. Reports show 129 million prescriptions were written for atorvastatin in 2022 in just the U.S. alone. Pharmaceutical company revenue from the sale of statins is now in the hundreds of billions worldwide. Drug producers like Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Merck & Co., Eli Lilly, and Bristol-Myers Squibb are all publicly traded corporations with a fiduciary responsibility to return a profit to their shareholders. With so much money on the line, the financial and economic interests involved in the debate over statins cannot be understated.

What Are the Benefits?

In plain language, a patient would choose to take a statin because they are looking to:

- Reduce their chance of dying prematurely

- Reduce their risk of having a non-fatal heart attack or stroke that results in significantly impaired quality of life

To make an informed decision, a patient needs to know whether the drug will offer these benefits.

Will You Live Longer? How Much Longer?

When extracting what’s meaningful from mountains of data, death is the ultimate endpoint that matters. It’s hard to fudge or manipulate, and it’s the one that patients care about the most. In the research, it’s called “all-cause mortality,” meaning died of anything. We don’t just care about reducing our chances of dying of one thing; we care about reducing our chances of dying at all.

So when it comes to statins, how much longer can you expect to live if you take them? A large meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials published in the British Medical Journal examined this question. In primary prevention (those who have not had a heart attack), death was postponed by a median of 3.2 days. In secondary prevention trials (those who have had a cardiovascular disease event), the median postponement of death was 4.2 days. Yes, DAYS. That is not a typo. In the studies examined, patients were taking statins for between 2 and 6.1 years and only gained a few days of extra life. This led the authors to conclude, “Statin treatment results in a surprisingly small average gain in overall survival.”

Maybe the data was analyzed improperly, or the length of treatment examined wasn’t long enough? Another analysis published several years later in the Journal of General Internal Medicine used longer trials and a different statistical method. It found the median postponement of death was 10 days. The highest risk patients, who experienced the most benefit, gained just 17.4 days of extra life.

Surprisingly small average gain, indeed.

What About Reducing Heart Attacks?

Many large-scale trials on the use of statins to reduce cardiovascular events have been conducted on a variety of populations, on different specific drugs, and for varying lengths of time. Often-cited trials are JUPITER, 4S, HOPE-3, ALCOT, LIPID, and the Heart Protection Study.

In basic terms, trials are conducted using large groups of people randomly divided into two groups. One group receives the statin and the other receives a placebo pill. They are followed for a period of time (usually five years or more), and the incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events such as heart attack or stroke is observed. This is called a Randomized Controlled Trial. It is considered “double blind” if neither the patients nor the researchers know who is taking the drug and who is taking the placebo. These steps are put in place to reduce bias and confounding of the data.

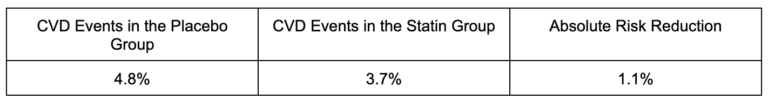

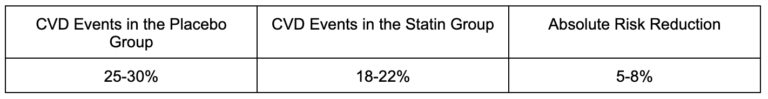

In Primary Prevention (treating people who have not had a heart attack or stroke), using HOPE-3 as an example, the results showed:

Stated in another way, among those taking the placebo (not taking statins), 95.2% did not have a heart attack. Among those taking the statin, 96.3% did not have a heart attack. Over 5.6 years, the difference in CVD events between taking the drug and not taking the drug is 1.1%. This is called the absolute risk reduction.

In secondary prevention (those who already have heart disease), amalgamation of results from trials like 4S, LIPID, and HPS shows more benefit for this high-risk population.

How to Lie With Statistics

If you’re like most people, a 1% risk reduction over five years sounds pretty underwhelming. We’re not going to sell a lot of drugs with numbers like that. This is where the marketing of these drugs comes in, and statistical chicanery that takes advantage of the poor understanding of math on the part of both the patient and the practitioner is used.

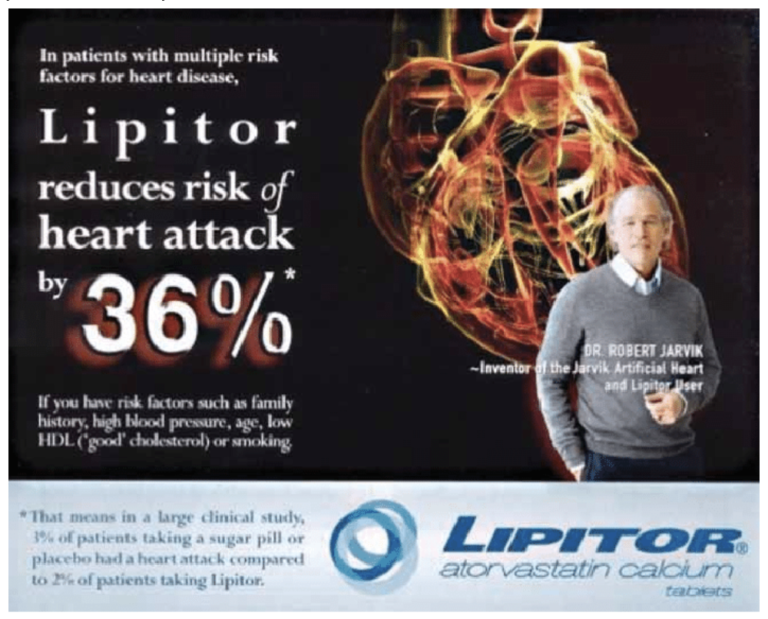

In this ad for the statin drug Lipitor, the small print states: “In a large clinical study, 3% of patients taking a sugar pill or placebo had a heart attack compared to 2% of patients taking Lipitor.” That’s a 1% absolute risk reduction. But what gets featured in the huge font in the center of the ad states “Lipitor reduced risk of heart attack by 36%”

How does 1% become 36%?

Enter: Relative Risk.

The drop from 3% to 2% is represented as a relative risk reduction of approximately one-third or 36%.

While this is technically correct, it is functionally very misleading. Ads like this cause many people to infer benefits from the drug, like, “If 1,000 people take Lipitor, we expect to prevent 360 heart attacks,” which is very, very far from reality. And it’s not just the general public either. Research shows that doctors are alarmingly bad at their understanding and interpretation of statistics, too.

Numbers Needed to Treat (NNT)

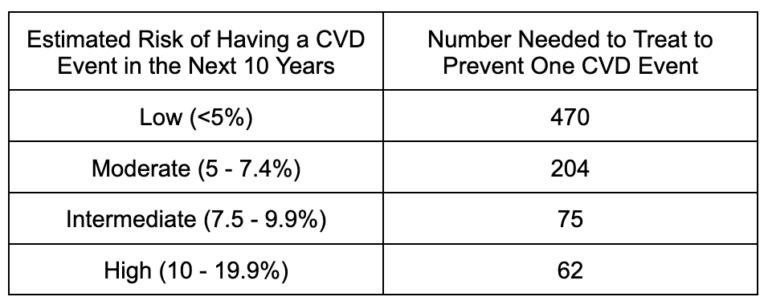

For doctors and patients to have meaningful conversations, both parties have to properly understand the risks and benefits of any treatment being considered. This is where the concept of Number Needed to Treat (NNT) becomes valuable. NNT refers to how many people need to take a drug for a given period of time to prevent one adverse outcome. It’s a method of representing numbers and statistics in a way that conceptually makes sense to the average person.

In the case of statins for primary prevention (people who haven’t had a heart attack or stroke), this analysis looked at the NNT for patients at low, moderate, intermediate, and high risk of having a fatal CVD event in the next 10 years. Methods like the SCORE model take into account a person’s age, sex, blood pressure, cholesterol (LDL, HDL, and total), and smoking status to estimate their risk over the next decade.

What this means is that for those in the <5% risk category, for example, 470 people need to take statins (usually for five+ years) to prevent one fatal CVD event. For every one person who benefits, 469 people will take the drug for years to decades and experience no measurable benefit at all (though they will certainly still be exposed to side effects). The NNT improves as the risk increases, with 62 people in the high-risk category taking statins to prevent one event, meaning 61 people take the drug with no benefit.

For secondary prevention (those who already have cardiovascular disease), the NNT also improves, often ranging between 30 and 50, depending on age, risk profile, and duration. Still, these numbers are less impressive than the public perception might suggest.

Note: To put these numbers in perspective versus the truly miraculous pharmaceutical drugs of the modern era, the NNT for antibiotics to treat bacterial pneumonia is two to five, and the NNT for Insulin in Type 1 diabetes is one.

What Are the Risks?

Of course, an informed patient must also evaluate the risks involved in any medical intervention. All drugs will have a multitude of effects. Some are desired effects, and some are undesired effects. The desired effects are why we take the drug, and the undesired effects are called “risks” or “side effects.” Whether the drug is worth taking is a decision based on the balance of benefits vs. side effects.

Statins are generally considered safe, but are known to have a multitude of side effects, mainly when prescribed over long durations.

Commonly reported side effects include:

- Muscle pain and weakness

- Fatigue and low energy

- Liver enzyme elevations

- Digestive disturbances

More serious risks include:

- Rhabdomyolysis — a severe form of muscle breakdown

- Increased risk of Type 2 diabetes — particularly in postmenopausal women or those with existing insulin resistance

- Cognitive issues — memory lapses or mood changes

The Undesired Effects

The story of statin side effects begins with the same pathway that makes the drug effective: the mevalonate pathway (mentioned above), which is the biochemical assembly line that produces cholesterol in your liver. Statins block the HMG-CoA reductase enzyme, which blunts the production of cholesterol and all other molecules downstream in the pathway. As we can see here, the mevalonate pathway also produces Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10), a critical molecule for antioxidant protection and mitochondrial energy production throughout the body.

Tissues that rely heavily on aerobic metabolism to meet high energy demand, such as the heart, skeletal muscle, brain, and kidneys, are particularly vulnerable to CoQ10 depletion. The result? Fatigue, muscle pain, and weakness. In rare cases, muscle fibers break down completely, releasing toxins that can damage the kidneys (that’s rhabdomyolysis). Although CoQ10 supplementation can reduce statin-induced muscle pain, it is not routinely recommended in standard practice.

The exact pathway also creates compounds called isoprenoids, which regulate insulin signaling and cell metabolism. When you disrupt those, you increase the risk of insulin resistance and Type 2 diabetes. This study followed nearly 9,000 men for six years and found a 43% increased risk of new-onset diabetes in those taking statin medication. An analysis of data from the Women’s Health Initiative found post-menopausal women to be hit the hardest, with a 48% increased risk of developing diabetes for those taking a statin versus not. This risk persisted across all types of statins and even after adjusting for BMI, physical activity, and diet. Across all populations, as the dose of statins increases, so too does the risk of developing diabetes.

As for the brain, cholesterol plays a significant role in maintaining neuronal membranes and synaptic function. Lowering brain cholesterol too much may subtly impair cognitive performance, leading to that foggy, forgetful feeling reported by some statin users. The effect is usually reversible by discontinuing the medication.

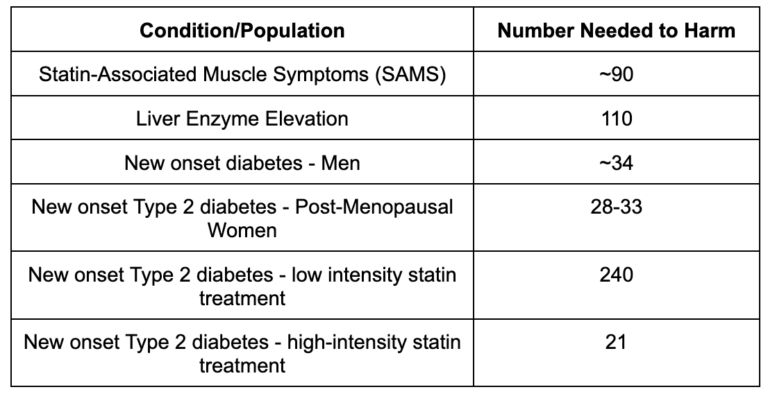

To evaluate risk, the sister number to NNT is called Number Needed to Harm (NNH) and reflects how many people have to take the drug for one person to experience harm from an adverse side effect. While a lower NNT is better (reflecting more patients benefiting from a drug), here a lower NNH is worse (reflecting a higher percentage of patients experiencing adverse side effects)

Now we have data to weigh the benefits and risks. For example, for a high-risk patient, one in 62 will benefit from taking a statin, while one in 21 will go on to develop diabetes (a risk factor for CVD in and of itself). For low-risk patients, one in 470 will benefit from taking a statin, while one in 240 will develop diabetes. Understanding these numbers allows patients to have meaningful conversations with their doctors and make fully informed decisions.

The Gap Between the Lab and the Real World

In industry-funded randomized controlled trials (the kind that get published in medical journals and used in guideline committees), statin side effects look impressively mild. Muscle pain, fatigue, or cognitive issues are usually reported in less than 1% of patients, and severe muscle injury (rhabdomyolysis) is described as “exceedingly rare.”

But when you observe actual patients, the numbers tell another story. Surveys of statin users consistently show that one in four people report muscle pain or weakness they attribute to the drug. In one extensive registry, 42% of current users and 63% of former users said they’d experienced at least one symptom while on a statin. Around one in five eventually stopped or switched medications because the side effects became intolerable.

Why such a massive discrepancy? Part of it comes down to trial design. Before most big statin trials officially begin, and before anyone is randomized to drug or placebo, there’s a quiet pre-trial stage called a run-in period. It sounds harmless, but what happens during this phase dramatically influences the results that follow.

In a typical run-in, every participant is given the statin (not a placebo) for several weeks or months. The purpose, according to study protocols, is to “ensure adherence and tolerance.” That means:

- Anyone who doesn’t take the pills consistently → excluded.

- Anyone who reports muscle pain, fatigue, sleep problems, digestive issues, or other side effects → excluded.

- Anyone whose liver enzymes or creatine kinase levels rise → excluded.

Only those who both tolerate the drug and comply perfectly move on to the actual randomized phase, where half receive the statin and half get a placebo. The result? By design, the trial population is pre-screened to include only the people least likely to experience side effects. This practice isn’t unique to statins, but it’s unusually common and consequential here because side effects are precisely what’s being debated.

By the time the official results are published, touting “no significant increase in muscle pain compared to placebo”, the data no longer reflect a real-world population. They reflect a handpicked, symptom-free subset.

To put numbers to it: in large statin trials like Heart Protection Study (HPS) and ASCOT-LLA, a staggering 30-40% of screened participants never made it past the run-in period. Some were excluded for lab abnormalities, some for non-compliance, and others for side effects. Those people simply disappear from the dataset. The irony is that these early dropouts represent the exact kind of patients who later show up in clinics complaining to their doctor of statin intolerance. They just never made it into the official statistics.

Another reason lab data does not match up with real-world experience is that trials also tend to recruit healthier, younger patients and exclude those with multiple medications or preexisting conditions, even though these are the exact people most likely to experience side effects in the real world.

Then there’s the simple fact that many side effects are subjective and easily dismissed. Complaints like “I feel tired,” “My legs ache,” or “I can’t think as clearly” rarely make it into a research paper. In older adults, aches, pains, fatigue, and subtle cognitive changes are often written off as “just getting older” and not flagged as potential drug-induced mitochondrial dysfunction.

What This Means

In reviewing the research, we can see that statins are neither a miracle cure nor exclusively bad. Certainly, people at the highest risk see the most benefit from these medications. For people who’ve already had a heart attack or stroke, although the side effects may be concerning, the absolute benefit is often significant enough to outweigh the risks. But for healthy individuals with low-to-moderate risk, the calculus isn’t so clear. The odds of meaningful benefit and meaningful harm are, at best, comparable.

The problem isn’t that statins never work; it’s that their benefits have been oversold with confusing statistics, their side effects underreported due to tricky study design, and patients have rarely been given the whole picture to make an informed decision.

Cardiovascular disease is not caused by a deficiency of statins or an excess of cholesterol alone. Decades of focus on lowering LDL-cholesterol have made the number itself the enemy. But cardiovascular disease is not caused by a single biomarker. It’s a complex, metabolic, inflammatory process driven by diet, lifestyle, and environment. When treatment success is measured by changes on a lab report rather than by improvements in human health and survival, we risk mistaking biochemical control for genuine healing.

For too long, we’ve treated the lab result instead of the person. Statins may lower a number, but they don’t build stronger hearts, cleaner arteries, or fitter humans. When lifestyle changes like quitting smoking, sound nutrition, strength training, metabolic conditioning, restorative sleep, and elimination of ultra-processed foods can drastically reduce cardiovascular risk without the need for medication, we should ask whether the true preventative medicine is found in the prescription pad or through the doors of any one of 10,000 CrossFit affiliates worldwide.

About the Author

Jocelyn Rylee (CF-L4) and her husband David founded CrossFit BRIO in 2008, starting in a modest 1500 sq ft space and focusing on personal training. Her dedication to excellence has also earned her a position on CrossFit LLC’s Level 1 Seminar Staff, a role that allows her to share her passion and expertise with aspiring coaches. Jocelyn holds specialties in Endurance, Gymnastics, Competition, and Weightlifting and is also a certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist through the NSCA. As a Level 2 Olympic Weightlifting Coach and a Level 3 referee, she has been deeply involved in the sport, even serving as a board member of the Saskatchewan Weightlifting Association for five years. Her achievements include being Saskatchewan’s top-ranked female Olympic Weightlifter from 2012 to 2015, during which she held provincial records in the Snatch, Clean & Jerk, and Total in her weight class. With an MS in Human Nutrition, Jocelyn loves sharing her knowledge on nutrition and performance through her blog and Instagram as “The Keto Athlete,” where she delves into the science of nutrition and its impact on athletic performance.

Jocelyn Rylee (CF-L4) and her husband David founded CrossFit BRIO in 2008, starting in a modest 1500 sq ft space and focusing on personal training. Her dedication to excellence has also earned her a position on CrossFit LLC’s Level 1 Seminar Staff, a role that allows her to share her passion and expertise with aspiring coaches. Jocelyn holds specialties in Endurance, Gymnastics, Competition, and Weightlifting and is also a certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist through the NSCA. As a Level 2 Olympic Weightlifting Coach and a Level 3 referee, she has been deeply involved in the sport, even serving as a board member of the Saskatchewan Weightlifting Association for five years. Her achievements include being Saskatchewan’s top-ranked female Olympic Weightlifter from 2012 to 2015, during which she held provincial records in the Snatch, Clean & Jerk, and Total in her weight class. With an MS in Human Nutrition, Jocelyn loves sharing her knowledge on nutrition and performance through her blog and Instagram as “The Keto Athlete,” where she delves into the science of nutrition and its impact on athletic performance.