Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide.

This year alone, an estimated 17.9 million people around the globe will die of a heart attack or other cardiovascular event. That’s more than the number of people who die from natural disasters, car accidents, plane crashes, and all types of cancers combined — a truly catastrophic loss of life.

And it’s not just the fatal events we need to worry about either. Each year, millions of people suffer a non-fatal heart attack. These events often leave survivors with significantly reduced cardiovascular capacity, persistent fatigue, and a lifelong need for medication and monitoring. Quality of life can be profoundly affected, with many unable to return to work, hobbies, sports, or their previous level of independence.

Most people think heart disease is something that happens later in life, a problem for seniors and the elderly. But in reality, the process begins decades earlier. Atherosclerosis (the gradual buildup of plaque in the arteries) can even begin in childhood. By the time symptoms like chest pain or shortness of breath emerge, the damage has been underway for decades. That means prevention must begin early, long before most people realize they’re at risk.

This series will explore the origins and drivers of cardiovascular disease through the lens of biology and biochemistry to better understand the disease. What is really going on inside the body as heart disease develops? When was heart disease first documented, and how did it rise to become the world’s number one killer? Most importantly, what choices are within our control to reduce risk, improve outcomes, and preserve our long-term health?

In this first installment, we’ll look at the history of heart disease and competing theories on its origins. In Part 2, we’ll examine cholesterol and its relevance to heart disease. In Part 3, we’ll examine the risks and benefits of the pharmaceutical approach to heart disease treatment, focusing on statins.

A Look Back Through History

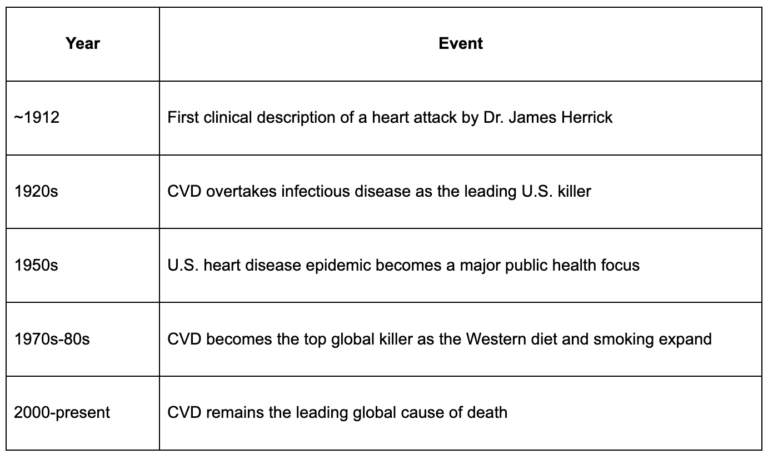

It may surprise you to learn that heart disease is a brand-new phenomenon of the modern era. The first clear clinical description of a heart attack in the medical literature didn’t occur until 1912, when Dr. James Herrick published a paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association describing “obstruction of the coronary arteries” as the cause of angina (chest pain) and sudden death. At that time, such cases were rare and mysterious.

Through the 1920s and 1930s, heart disease rose to become the No. 1 cause of death in the U.S, overtaking infectious diseases (like tuberculosis and pneumonia) as sanitation improved and antibiotics became widespread.

By the 1950s, heart attacks had reached epidemic proportions, especially among middle-aged men. CVD became the leading global cause of death by the 1970s-1980s, as urbanization, industrialized food systems, smoking, and sedentary lifestyles spread across developing nations.

What Is An Atherosclerotic Plaque?

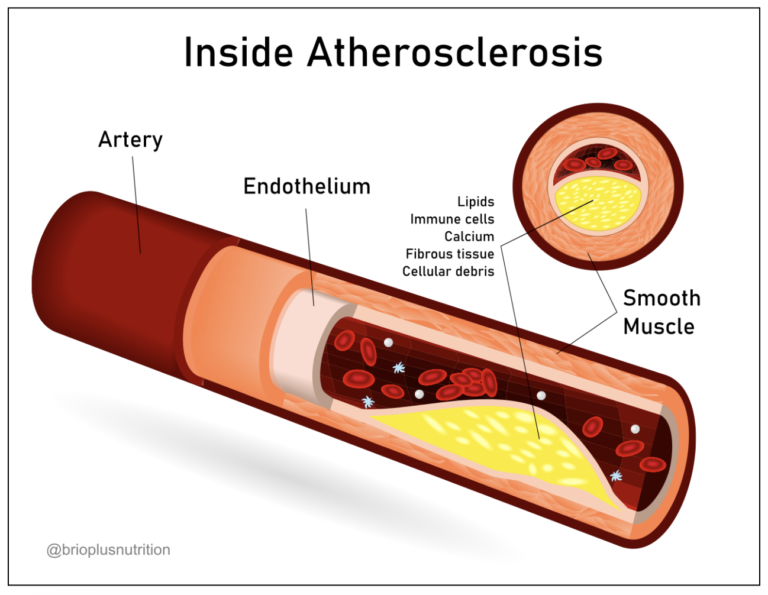

An atherosclerotic plaque is a complex, multicellular structure that forms within the walls of arteries. It begins when the endothelium (the thin inner lining of blood vessels) is damaged by various factors, including high blood pressure, environmental toxins (such as smoking or air pollution), oxidative stress, or elevated blood sugar. In response to this injury, the body initiates a healing process, and part of that process involves the recruitment of lipid-carrying particles like low-density lipoproteins (LDL). These particles are drawn to the site of damage to help repair the vessel wall. However, once LDL particles enter the damaged area, they are susceptible to oxidation. Oxidation is a chemical reaction that occurs when molecules are exposed to oxygen, the same process that causes metal to rust, walnuts to go rancid, and apple slices to turn brown. In the body, this process alters LDL particles, making them more inflammatory and damaging to tissues.

The immune system recognizes oxidized LDL as a threat and responds by sending white blood cells (particularly monocytes, which become macrophages) to the site. The macrophage (literally meaning big eater) engulfs and digests the oxidized LDL, and becomes a foam cell in the process. Foam cells accumulate and form the fatty streaks that are the earliest stage of plaque development.

As the plaque grows, it contains a mix of inflammatory cells, smooth muscle cells, cholesterol, calcium deposits, and fibrous tissue. Over time, the plaque can become hardened and calcified, narrowing the arterial opening and restricting blood flow. Alternatively, the fibrous cap of the plaque can rupture, triggering the formation of a thrombus (blood clot). If the clot significantly blocks blood flow to the heart or brain, it can result in a heart attack or stroke.

In this way, plaque doesn’t simply “clog” the arteries; it initiates a chronic, inflammatory process that compromises blood flow and sets the stage for acute cardiovascular events.

What Changed?

By the 1950s, heart attacks had exploded into an epidemic, claiming the lives of middle-aged men in particular and becoming a top health priority in the Western world.

How did a previously unheard-of disease rise to become the number one killer in just a few decades?

The modern era brought about a combination of environmental and lifestyle shifts that set the stage for a heart disease epidemic:

- Food quality declined: Traditional diets, which were based on home-cooked meat, fish, eggs, natural fats, and seasonal fruits and vegetables, were displaced by ultra-processed foods loaded with refined sugars, enriched flours, and industrial seed oils.

- Physical activity decreased: Automation of labor, the rise of office jobs, and widespread automobile use reduced daily movement.

- Smoking became widespread: Cigarette consumption increased dramatically during and after the World Wars. By the 1940s and 1950s, smoking was deeply ingrained in American culture, with over 40% of U.S. adults regularly smoking cigarettes. It was even promoted by doctors in advertisements and widely accepted in workplaces, airplanes, and homes.

Theories of Heart Disease

In 1955, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower suffered a massive heart attack while in office, bringing the issue of cardiovascular disease into the national spotlight. His illness underscored the urgency of addressing heart disease and helped accelerate public awareness and research funding. Scientists raced to identify the cause (never mind that he was known to smoke 4-6 packs a day).

The Lipid Hypothesis, proposed by physiologist Ancel Keys, suggested that dietary saturated fat raised blood cholesterol levels, which contributed to the development of atherosclerosis and heart attacks. Keys first gained prominence through his “Seven Countries Study,” an epidemiological investigation that claimed to show a strong correlation between saturated fat intake and heart disease mortality. However, critics later pointed out that Keys had access to data from 22 countries but chose to cherry-pick only the seven that supported his hypothesis, ignoring the others that contradicted it.

Keys was known for his assertive and combative personality. He dominated the scientific discourse of his time, aggressively dismissing dissenting voices, most notably that of British physiologist John Yudkin, who implicated sugar rather than fat as the primary dietary culprit of heart disease.

In 1972, Yudkin published a book, “Pure, White, and Deadly,” and laid out the case that sugar, not fat, was the real driver behind rising rates of obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. He warned that excess sugar consumption was silently harming public health. He argued that it promoted insulin resistance and chronic inflammation, both of which are now understood to play central roles in cardiovascular disease. In 2025, metabolic health is at the center stage in the discussion around the chronic disease epidemic, meaning Yudkin was right. At the time, though, his warnings were largely ignored.

Industry Meddling in “The Science”

In 2016, a paper was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) revealing documentation that in the 1960s, the sugar industry paid prominent Harvard scientists to publish papers downplaying the risks of sugar and instead shifting the blame for heart disease onto saturated fat. One such paper, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1967, was funded by the Sugar Research Foundation (now the Sugar Association) and failed to disclose the conflict of interest. This strategic manipulation of scientific literature pushed public health policy and consumer behavior away from sugar reduction and toward low-fat diets. As early as 1954, internal documents revealed that the sugar industry knew if Americans shifted toward a low-fat diet, it would result in an estimated 30% increase in consumption — and therefore sales — of sucrose. This shift has no doubt contributed to the meteoric rise in obesity and metabolic disease since that time.

The influence of Keys (and the meddling of the Sugar Industry) shaped decades of dietary guidelines and public health messaging, even as the evidence for his theory remained incomplete and highly contested. The lipid hypothesis oversimplified a complex disease process by framing cholesterol as a harmful substance rather than a vital component of human biology, and it offered no precise mechanism for how cholesterol could cause such harm. Despite these weaknesses, the Lipid Hypothesis rose to dominate the public and medical discourse for decades, and remains pervasive to this day.

Next up, in Part 2, we take a deep dive into understanding cholesterol.

About the Author

Jocelyn Rylee (CF-L4) and her husband David founded CrossFit BRIO in 2008, starting in a modest 1500 sq ft space and focusing on personal training. Her dedication to excellence has also earned her a position on CrossFit LLC’s Level 1 Seminar Staff, a role that allows her to share her passion and expertise with aspiring coaches. Jocelyn holds specialties in Endurance, Gymnastics, Competition, and Weightlifting and is also a certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist through the NSCA. As a Level 2 Olympic Weightlifting Coach and a Level 3 referee, she has been deeply involved in the sport, even serving as a board member of the Saskatchewan Weightlifting Association for five years. Her achievements include being Saskatchewan’s top-ranked female Olympic Weightlifter from 2012 to 2015, during which she held provincial records in the Snatch, Clean & Jerk, and Total in her weight class. With an MS in Human Nutrition, Jocelyn loves sharing her knowledge on nutrition and performance through her blog and Instagram as “The Keto Athlete,” where she delves into the science of nutrition and its impact on athletic performance.

Jocelyn Rylee (CF-L4) and her husband David founded CrossFit BRIO in 2008, starting in a modest 1500 sq ft space and focusing on personal training. Her dedication to excellence has also earned her a position on CrossFit LLC’s Level 1 Seminar Staff, a role that allows her to share her passion and expertise with aspiring coaches. Jocelyn holds specialties in Endurance, Gymnastics, Competition, and Weightlifting and is also a certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist through the NSCA. As a Level 2 Olympic Weightlifting Coach and a Level 3 referee, she has been deeply involved in the sport, even serving as a board member of the Saskatchewan Weightlifting Association for five years. Her achievements include being Saskatchewan’s top-ranked female Olympic Weightlifter from 2012 to 2015, during which she held provincial records in the Snatch, Clean & Jerk, and Total in her weight class. With an MS in Human Nutrition, Jocelyn loves sharing her knowledge on nutrition and performance through her blog and Instagram as “The Keto Athlete,” where she delves into the science of nutrition and its impact on athletic performance.