This 2020 trial evaluated correlations between various physiological/performance measures and total time to complete Murph (1).

Researchers recruited 11 subjects from various CrossFit boxes. All had done CrossFit two or more times weekly for at least six months; mean CrossFit experience was four years. All subjects were male and between the ages of 21 and 31.

Subjects were weighed, and body composition was measured via DEXA. Performance benchmarks were then assessed as follows:

- Muscular strength: 1-rep-max bench press and back squat

- Muscular endurance: Number of bench presses completed at 50% of 1-rep max

- Anaerobic power: 30-second Wingate test

- Aerobic capacity: Treadmill test of V02 max

No fewer than 72 hours after these assessments were done, participants returned to the research site to perform Murph for time. Participants did not wear a weight vest.

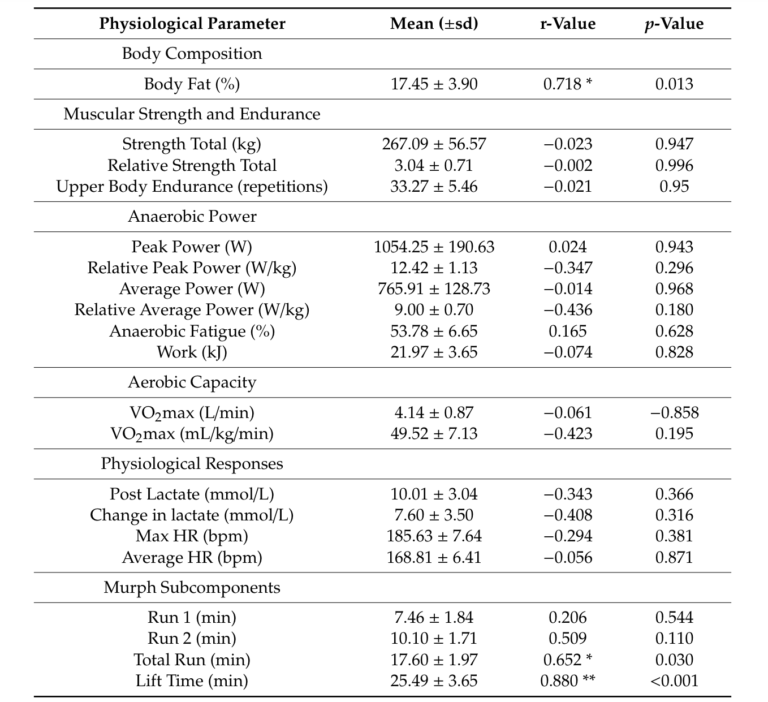

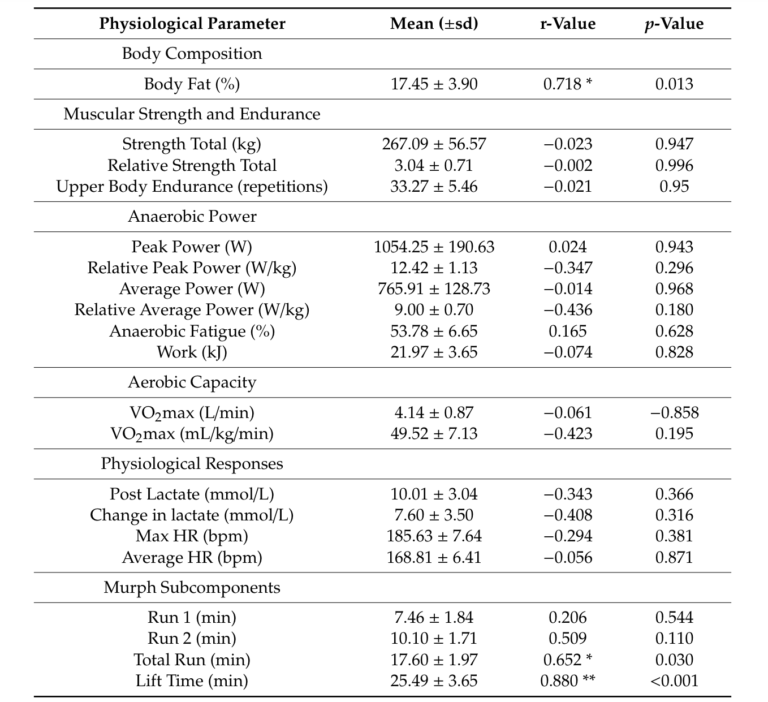

Participant characteristics are summarized in the tables below.

Table assessing participant physiological parameters and physiological responses to Murph, respectively. R-values indicate correlation with overall Murph time, and p-values indicate the significance of these associations.

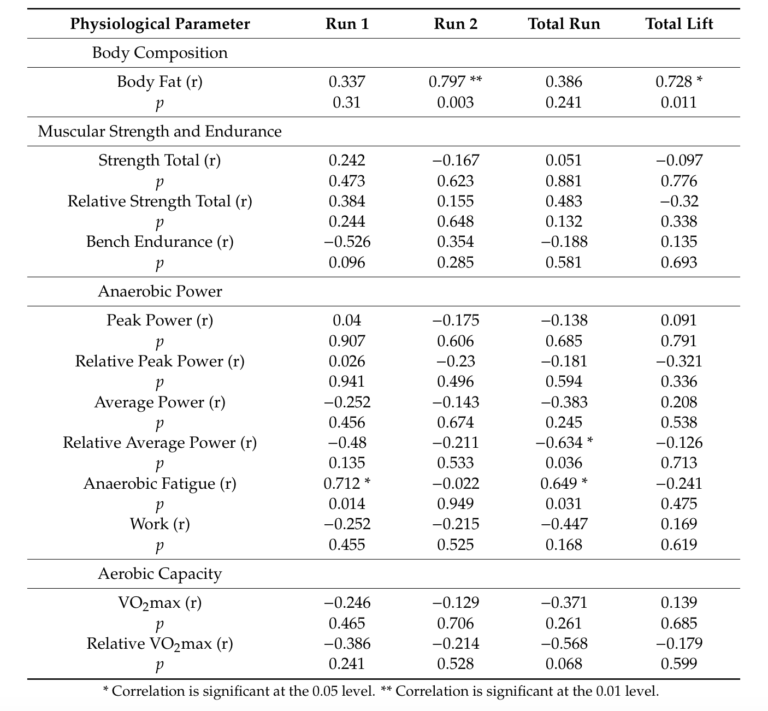

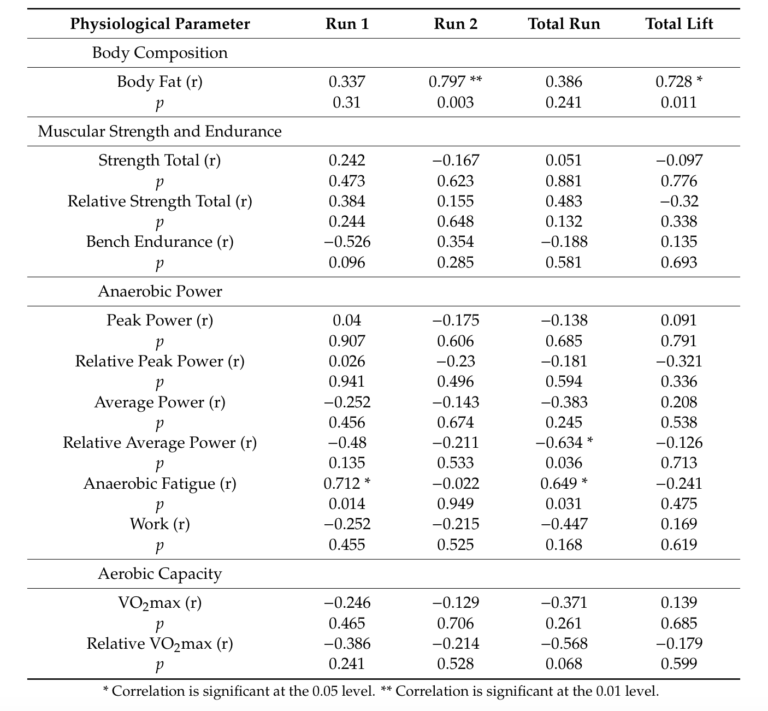

Correlations between physiological parameters and individual Murph components

Post-Murph lactate averaged 10.01 mmol/L. Max heart rate averaged 185.63 bpm, and mean heart rate averaged 168.81 bpm. Mean Murph completion time was 43.43 minutes, ranging from 36.56 to 54.21 minutes. Neither heart rate nor lactic acid levels correlated with total Murph time.

Lower body fat percentage significantly predicted lower total Murph time. On average, 58% of total time was spent on the push-ups, pull-ups, and squats; and 42% was spent on the two runs, with time to complete the middle section a stronger predictor of total Murph time than time to complete the run sections.

Interestingly, neither muscular strength nor muscular endurance predicted total time to complete Murph or time to complete the middle section. Similarly, VO2max did not predict either total Murph time or time to complete the running sections.

Researchers assessed tolerance of anaerobic fatigue as the rate of decrease in power during the 30-second Wingate test; higher performance in this measure correlated with significantly reduced time to complete the two runs. Increased anaerobic — not aerobic — power similarly correlated with a lower Murph run time.

Taken together, these results suggest body fat content and tolerance of anaerobic fatigue are the clearest determinants of Murph time within this small sample. Previous research across varied exercise disciplines has found a correlation between reduced body fat and increased performance (2). It is reasonable to expect this relationship to be even stronger within the context of Murph, given it consists entirely of body-weight exercises.

The researchers noted with surprise that VO2 max did not correlate with either overall Murph time or time to complete the run sections. Previous literature has shown, however, that measures of anaerobic fatigue, such as those tested here, correlate with performance in endurance-trained athletes (3). This suggests training programs that improve lactate tolerance may improve performance in high-intensity endurance tests like Murph; the high mean heart rate levels and high lactic acid levels reported suggest significant demand on anaerobic metabolism throughout the exercise period.

Overall, this study somewhat surprisingly found that neither muscular strength, muscular endurance, nor aerobic capacity correlated with Murph performance. Conversely, reduced body fat and increased tolerance of anaerobic fatigue predicted better times. These subjects were moderately trained. Therefore, these results may not predict results within either untrained or elite athletes. However, they may serve as a useful guide to the factors governing performance in many CrossFit athletes.

Comments on Physiological Predictors of Performance on the CrossFit Murph Challenge

6 Comments

As a mathematician / statistician I love to see the numbers. Beyond that, as a CrossFitter, it's great to see researchers looking at Murph as a measure of fitness and something worth analyzing. There's still a lot we don't know...

Résumé/traduction en Français

Prédicteur physiologiques de la performance sur Murph

Question : Quelles métriques physiologiques et de performances peuvent prédire un temps sur Murph

Conclusion rapide :

Dans ce petit sample, le pourcentage de masse grasse était le seul prédicteur du temps d’un athlète sur Murph.

La mesure de la fatigue anaérobique (et pas la capacité aéro bique) a prédit le temps pour compléter la portion de course de l’entraînement.

____

11 sujets de différentes boxs Tous ont fait du CrossFit 2 ou 3 fois par semaine pendant au moins 6 mois avec comme expérience moyenne 4 ans.

Tous des hommes entre 21 et 31 ans

Les sujets ont été pesés et la composition corporelle ont été mesurées.

Force musculaire : 1 rep max bench press et back squat

Endurance musculaire : Nombre de rep au bench à 50% de la rep max

Puissance anaérobique : 30 sec Wingate test

Capacité aérobic : Test treadmill V02max

Moins de 72 heures après ces tests, les participants ont fait Murph sans gilet lesté.

Rythme cardiaque max: 185bpm Moyenne du rythme cardiaque : 168bpm

Moyenne du temps au murph : 43 minutes (36-54min)

Ni le rythme cardiaque ni le niveau d’acide lactique étaient corrélés avec le temps total du Murph.

En revanche un taux de masse grasse plus faible a prédit de manière significative un temps plus rapide au Murph.

En moyenne 58% du temps a été passé sur la gym et 42% sur la course.

Le temps passé sur la gym était un meilleur prédicteur du temps au murph.

De manière intéressante, ni la force musculaire ni l’endurance musculaire n’ont pu prédire le temps total sur Murph ou le temps complété sur la section de gym. Similairement, la v02 max n’a pas pu prédire le temps total au murph et le temps pour compléter la course.

Une capacité anaérobique supérieure était corrélée avec un temps plus rapide au Murph.

Mis ensemble, ces résultats suggèrent que la masse grasse et la tolérance à la fatigue anaérobique sont des déterminants du temps au Murph pour ce sample.

La V02 max n’a eu aucune corrélation avec le temps total au Murph.

Cela suggère qu’un programme d’entraînement qui améliore la tolérance lactique pourrait améliorer la performance sur des testes d’endurance à haute intensité comme Murph.

Une moyenne élevée du rythme cardiaque et un niveau d’acide lactique élevé montre qu’il y a une demande significative sur le métabolisme anaérobique pendant cette période d’exercice.

Ces sujets étaient modérément entraînés et ces résultats ne sont donc surement pas des prédicteurs d’athlète non entraînés ou élites mais ils peuvent servir de guide permettant de déterminer la performance chez les athlètes de CrossFit.

Really great study. I just completed 30 days of Murph. I'm 50, would consider myself an average crossfitter. 5'11 and 185lbs...

throughout the 30 days my weight stayed exactly the same.. nutrition didn't really change apart from Protein intake and water consumption... both increased of course. Your average times across all athletes, are pretty close to mine throughout the duration of 30... times ranging from 38mins to 52 mins... Most significant for me was doing Muprh on memorial day alone with a vest unpartitioned took 58 mins.. (this was a week before my 30 days started) and then the last Murph of the 30 days again with a vest, unpartitioned, BUT with 8 others in a gym setting, took 44 mins... partly increased physical fitness, and partly collective suffering.. that latter making the biggest impact for sure during the 30 days. significant improvement in pull up ability over the 30 days of course made a huge impact... at the start, I struggled to comfortably string 5 pull ups. at the end, sets of 10 were no challenge. would have been good to do a more scientific study over the time... Body fat %, body composition etc... will try to sort that for the next challenge... Thanks for the study.

Interesting article to read...

Mike - 30 days of Murph - that's a lot...what prompted this experiment?

Hi Nuno,

I Turned 50, wanted a physical and mental challenge.

Well done. Wouldn't recommend it but its a strong challenge :D