This 2011 review summarizes many of the biological correlates of major depressive disorder (MDD). The majority of the data presented illustrates associations between depression (and/or depression severity) and various biochemical markers. It therefore cannot determine whether depression causes the observed elevations and suppressions or is caused by them. Taken together, however, these data illustrate a clear biochemical basis for depression. They also suggest depression and its comorbidities — which include elevated risk of a variety of conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, and impaired immune function (1) — may be mediated by direct treatment of the relevant biomarkers.

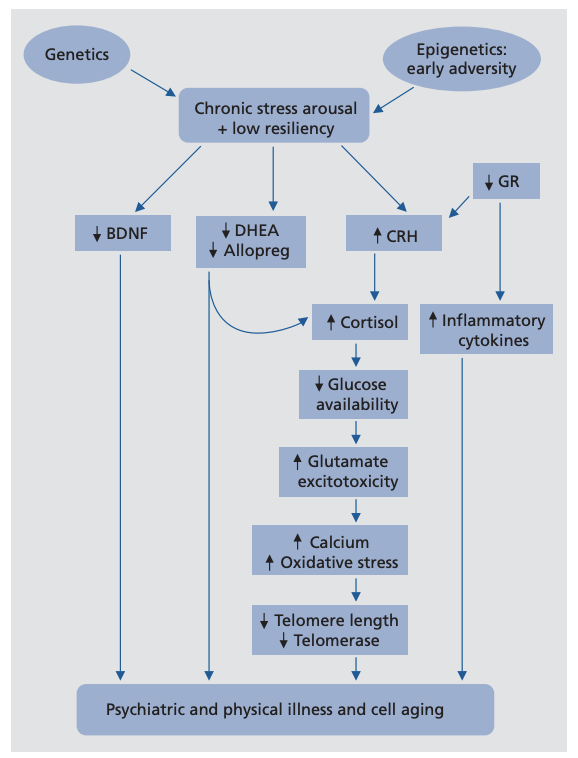

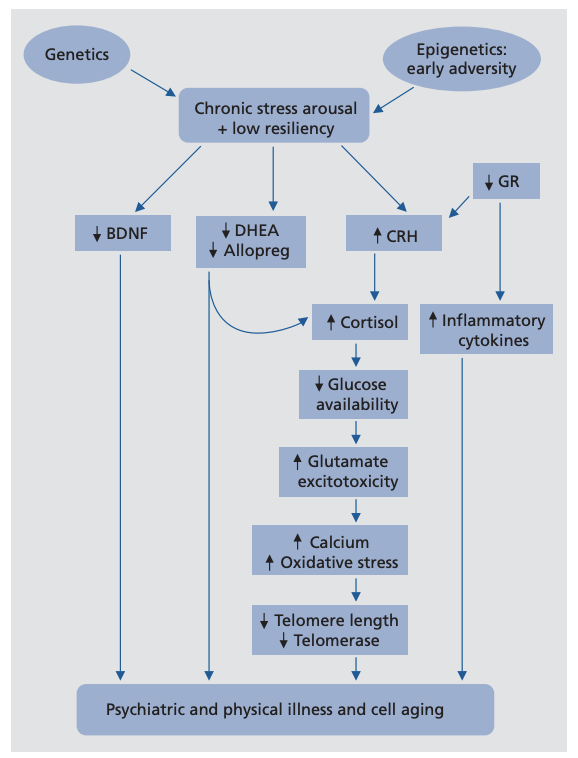

The authors propose a comprehensive disease model, illustrated in the figure below. This model links MDD to elevation or suppression of a variety of biochemical systems and outlines the extensive downstream effects of the chronic stress increase associated with MDD. As such, this model, which has been explored in previous publications, explains both how these biological factors can directly contribute to MDD and how MDD, via its biological effects, leads to its various comorbidities (2).

Figure 1: This model illustrates a variety of pathways associated with MDD that contribute to pathologies associated with depression and aging

The top of the figure represents hyperactivity of the LHPA axis, one of the two major moderators of the biological stress response (3). Psychological stress can clearly trigger a depressive episode (4), specifically when the psychological impact of a stressor exceeds the coping ability of the individual (5). Coping ability may itself have a biological basis, which was reviewed in previous literature (6). Early-life adversity may predispose an individual to LHPA axis hyperactivity and so increase sensitivity to initiation of this cascade (7). This model thus explains why childhood adversity has been frequently linked to a variety of conditions associated with impaired metabolism and aging (8). By increasing the sensitivity of the individual to stress, these experiences increase risk of exposure to the various metabolic defects described in this model.

A major downstream consequence of MDD is elevated glucocorticoid (the most important of these being cortisol) levels, which are present in the majority of depressed individuals but not all (9). High cortisol levels may be particularly harmful alongside elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines, which inhibit the action of cortisol by downregulating cortisol receptor activity (10). High cortisol levels may directly contribute to cell damage and death in a variety of cell types, including hippocampal cells, in part by impairing effective regulation of cellular glutamate (11).

Unmedicated depressives display low levels of neurosteroids, including GABA-A, DHEA, and allopregnanolone; treatment and remission of depression restores normal levels (12). Neurosteroids, in addition to directly modulating the LHPA axis, support healthy immune system activity and have antioxidant and neuroprotective effects (13). Under chronic stress, low levels of these neurosteroids could increase the vulnerability of the LHPA axis to dysregulation and increase individual sensitivity to external stressors (14). This is acutely apparent in the context of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), which includes severe physical and emotional symptoms correlated with a failure to elevate neurosteroid levels effectively in response to external stressors (15).

Insulin resistance and impaired glucose tolerance are frequently seen in individuals with MDD, especially those who are hypercortisolemic (16). These effects may be directly related to the effect of cortisol on glucose levels and glucose utilization; for example, one PET scan study showed cortisol directly inhibited hippocampal glucose utilization in otherwise healthy individuals (17). This suggests a major mechanism by which depression-induced hypercortisolemia leads to many of the comorbidities of MDD, including metabolic and neurodegenerative disease (18).

MDD is also associated with the elevation of a variety of inflammatory cytokines and elevated net inflammatory burden. These chronically elevated levels of inflammation can impair immune function and increase risk of serious comorbidities (19). Similarly, these elevated levels of inflammation may directly impair hippocampal function, as the hippocampus is rich in IL-6 receptors (20). Similarly, chronically elevated LHPA axis activity, as seen in MDD, increases oxidative stress, which, particularly alongside elevated inflammation, contributes to PTSD, stroke, neurodegenerative conditions, and other conditions typically associated with aging (21). Interestingly, many antidepressants have antioxidant effects (22).

Finally, according to the so-called “neurotrophic model,” depression results from impaired neurogenesis and neuroplasticity, itself the result of low hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) activity. Low serum BDNF levels are consistently observed in unmedicated depressives, and this theory is central to the mechanism of action of multiple prominent antidepressants (23). Similarly, direct BDNF administration acutely reverses depressive behaviors in mice, suggesting it has direct biological effects and is not merely a marker of disease (24). More recent research has begun to establish BDNF as a metabotrophin, with significant effects in the periphery; low BDNF levels, for example, are correlated with insulin resistance and impaired glucose tolerance (25). The low BDNF levels seen in MDD, therefore, may play a major role in moderating the relationship between MDD and Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, and other metabolically influenced conditions (26).

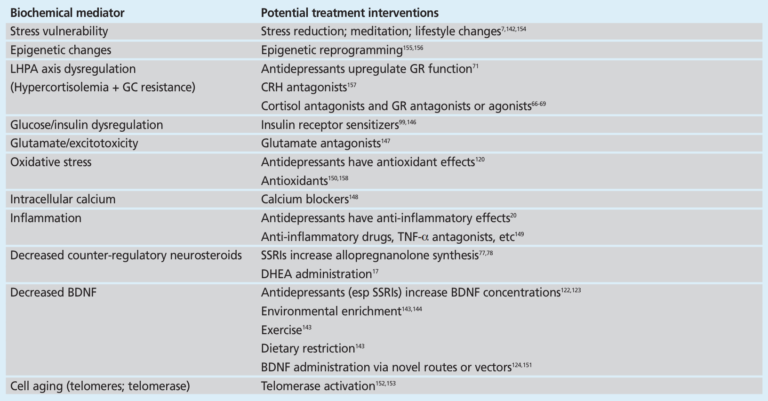

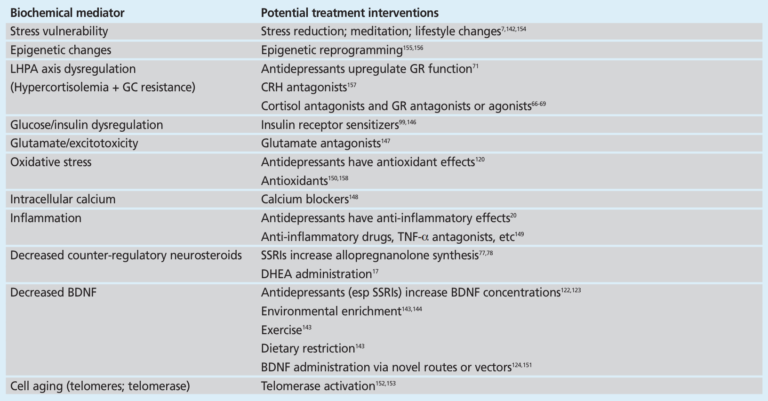

The authors of this review conclude by noting the implications of these findings. The majority of the relationships described are associations, and thus it is not clear to what extent MDD is the cause of these biochemical distortions and to what extent they contribute to the genesis, perpetuation, and/or exacerbation of MDD. The existence of these biochemical mediators, however, and the consistent links between them, depression, and its comorbidities suggest there is a clear biological basis for depression; furthermore, these findings suggest direct treatment of these biochemical distortions is a potential avenue to treat, manage, or even reverse MDD. As shown in the table below, many of the existing tools used to manage these mediators are lifestyle interventions related to diet, exercise, and general health and well-being. This biological framework suggests these and similar treatments have the potential to prevent and treat major depressive disorder and, at minimum, to reduce the comorbidity risks associated with depression.