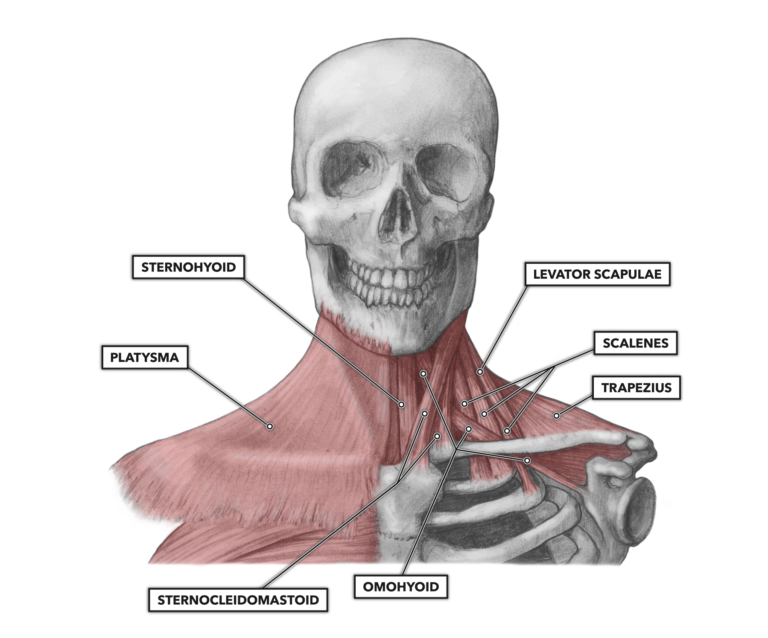

The cervical vertebral skeleton serves as an attachment for a large number of muscles that create a complex set of moving connections between the skull, vertebrae, scapulae, clavicles, sternum, and ribs.

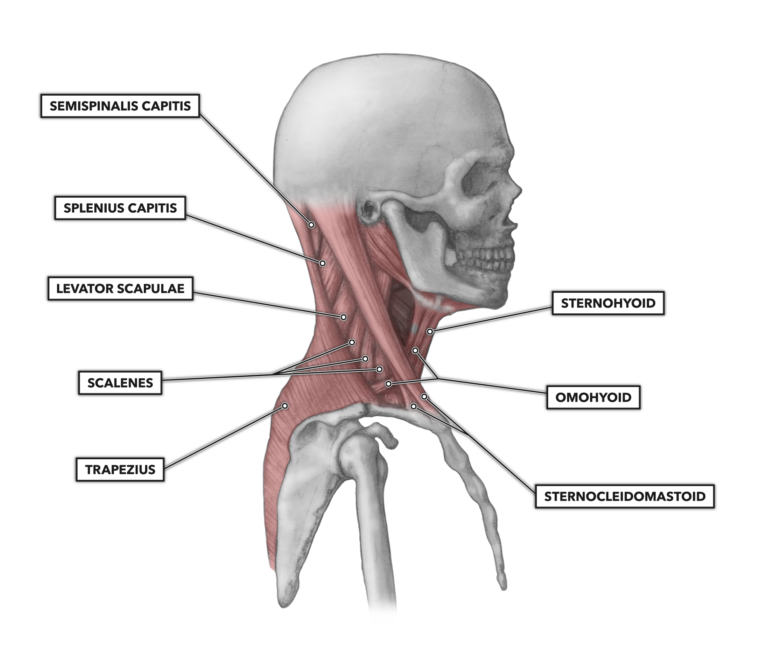

Figure 2: Lateral view of the cervical musculature

Sternocleidomastoid – This pair of muscles creates the characteristic v-shape rising from the top of the sternum to the rear jawline. The sternocleidomastoid muscle attaches to both the superior sternum and clavicle near the sternoclavicular joint and runs upward. It attaches to the mastoid process just posterior to the acoustic meatus (behind the ear).

This pair of muscles is relatively pronounced in powerlifters who do heavy bench presses routinely, as the muscle is recruited to elevate the chest in order to shorten the distance between the chest and lockout position at the top of the movement.

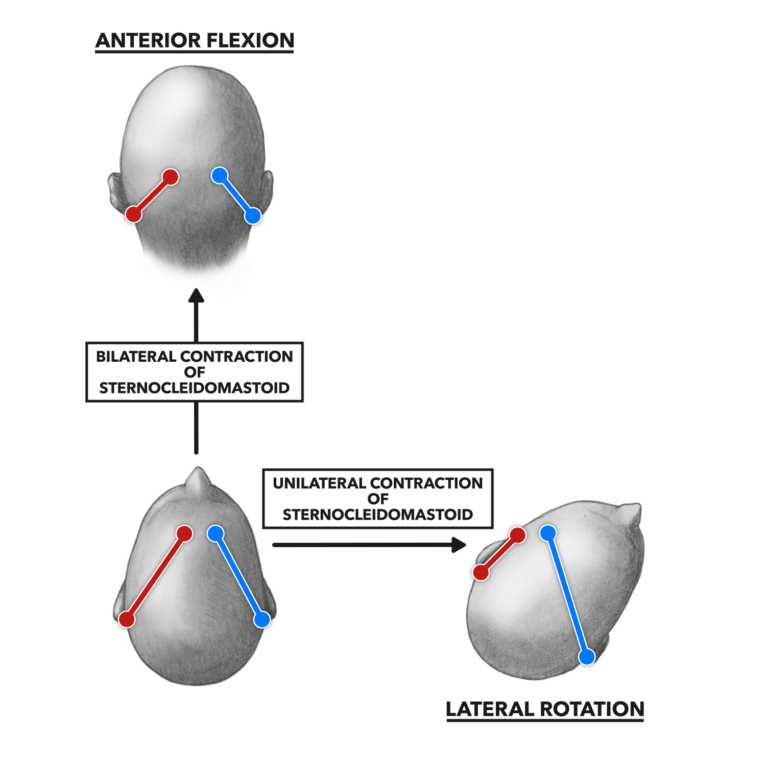

When recruited unilaterally, the sternocleidomastoid tilts the head toward the activated side of the muscle and can rotate the head so it faces the opposite side. When recruited bilaterally, it flexes the neck or raises the sternum (whichever end is held most stable). This latter action contributes to forced inspiration (voluntarily taking as big a breath as you can). Together, the two sides of the muscle produce movements such as nodding and turning the head.

Scalenes – There are three individual scalenus muscle segments: anterior, medius, and posterior. These segments are attached to the transverse processes of the second through seventh cervical vertebrae and the first two ribs.

The scalenes lie along the anterior-lateral aspect of the neck and assist in lateral flexion of the head against resistance (tilting the head to the left or right). The scalenus anterior and medius, when contracted, elevate the first rib or rotate the neck to the opposite side of the body (i.e., the left scalenus rotates the head to the right). The scalenus posterior elevates the second rib or tilts the head to the same side of the body.

Platysma – This muscle pair attaches to the skull at the inferior border of the mandible. It also attaches to the fascia over the lower face, as well as skin fascia lower on the body (over the neck, chest, and shoulders). It pulls the mandible down (opening the mouth) and deforms and wrinkles the skin of the lower face, mouth, and neck (grimacing).

Levator scapulae – This pair of muscles attaches to the transverse processes of cervical vertebrae 1 through 4. Distally, it attaches to the medial border of the scapula. When the head is held stable and the muscle contracts, it raises the medial aspect of the scapula. If the scapula is held stable, the head will be tilted laterally.

Sternohyoid – This is a medial pair of muscles, attached to the hyoid bone and located inferior to the lateral, posterior, superior aspect of the manubrium of the sternum. The primary action of the sternohyoid is to depress (pull down) the hyoid bone and thus the larynx.

Omohyoid – This pair of muscles arises medially from the inferior aspect of the hyoid bone and attaches distally to the superior and lateral scapula, posterior to the coracoid process. It carries out the same function as the sternohyoid — to depress the hyoid bone — but it is a relatively unique muscle with two muscle bellies separated by a central tendon.

Movement

The vertebral column is capable of considerable movement, owing to the extensive number of joints it contains. The cervical vertebrae display the greatest range of movement due to the structure of the atlas and axis under the skull. Combined, the cervical vertebrae are capable of flexion, extension, lateral flexion, and rotation. The musculature here occurs in bilateral pairs, which means the cervical muscles are structured symmetrically across either side of the vertebral column. For example, you have a sternocleidomastoid on the left side of the neck and you have a sternocleidomastoid on the right side of the neck, forming a bilateral pair. This bilateral arrangement, along with separate innervations to each muscle of the pair, allows these muscles to act both together (bilaterally) to produce symmetrical motion and individually (unilaterally) to produce asymmetric movement.

Figure 3: The sternocleidomastoid muscle provides a good example of the separate and combined effects of the muscle pair’s contraction. The two sides of the muscle can provide symmetrical and equivalent support in normal cranial posture, provide bilateral contractile force and flex the cervical vertebrae, or contract unilaterally to rotate the head.

Analysis of what vertebral muscles do is fairly simple. Muscles attaching on the anterior surface of the column will cause flexion. Muscles on the posterior surface cause extension. Muscles used unilaterally produce lateral flexion. Selected recruitment of opposing and complementary individual anterior and posterior muscles will produce rotation. Often you will find that simultaneous contraction of muscle pairs does not produce any motion; rather, it produces joint stabilization through isometric force production.

To learn more about human movement and the CrossFit methodology, visit CrossFit Training.