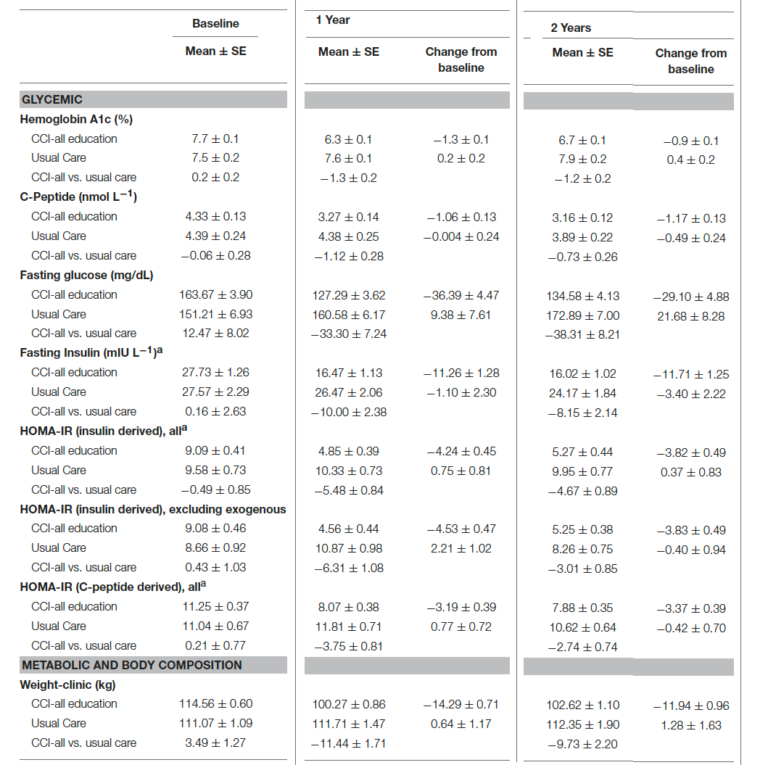

Diabetes is understood as a global disease, but there is no escaping the primacy of blood glucose and the effectiveness of dietary reduction. In some sense, there is nothing surprising about Hallberg et al.’s results, which are consistent with much work in the literature; they represent a breakthrough in their clear demonstration of point 1 of our review:

Point 1. Hyperglycemia is the most salient feature of diabetes. Dietary carbohydrate restriction has the greatest effect on decreasing blood glucose levels.

When Drugs Are not Enough

Drug advertisements or the insert in the package are likely to advise using the medication “when diet and exercise are not enough.” The idea that diet — or frequently, “lifestyle” changes — constitute the first approach to treating diabetes appears to be followed as much in the breach as in the observance. Critical is the implication that all dietary or lifestyle changes are the same, because this idea suggests little effort will be put into finding the limits after which drugs should be introduced. Point 11 from our review is relevant here:

Point 11. Patients with Type 2 diabetes on carbohydrate-restricted diets reduce and frequently eliminate medication. People with Type 1 usually require lower insulin.

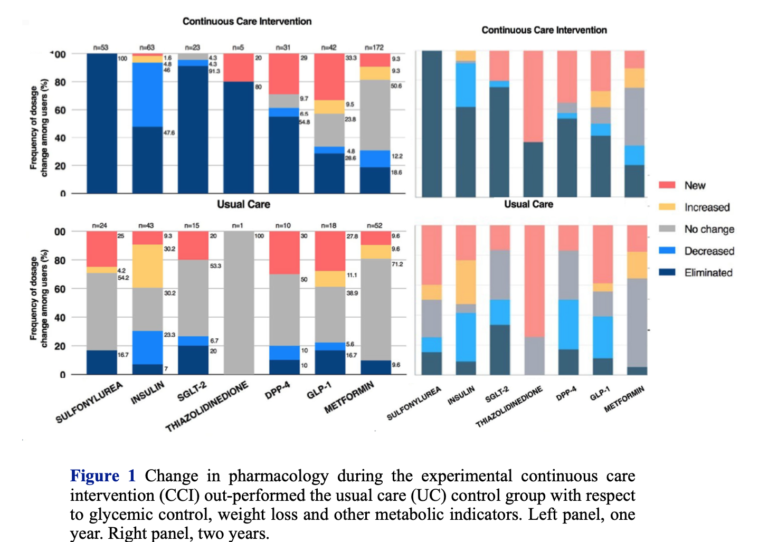

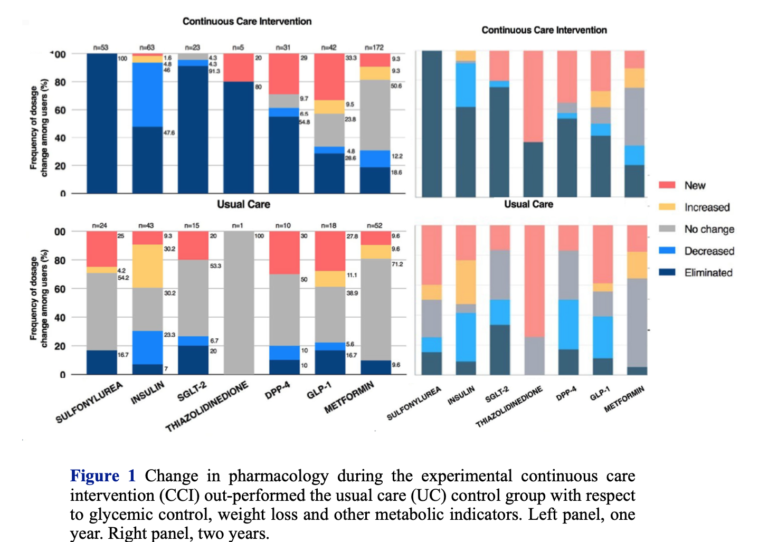

Drugs remain the mainstay of diabetes treatment, and despite the benefits, not needing a drug is always a sign of progress. Hallberg’s study (2, 3) shows that not all lifestyle changes are the same; overall, the low-carbohydrate/keto groups used half as many drugs as the control. A majority of the CCI participants (53.5%) met the criteria for diabetes reversal (meaning they were using only metformin). Another 17.6% achieved remission (i.e., requiring no medication). Of particular importance is the observation that 95% of people on insulin reduced or eliminated use.

Weight Loss

The resistance of the medical orthodoxy to the principle of carbohydrate restriction remains incomprehensible. In fact, one has to face the bizarre paradox that diabetes drugs are designed to reduce blood glucose in any number of ways while nutritional approaches and weight loss are considered primary, notwithstanding the universally accepted observation that many people with Type 2 diabetes are not fat and many overweight people do not develop diabetes. The insistence on weight loss is one of the objectionable aspects of traditional advice: It is, after all, not easy to lose weight, and emphasizing weight rather than glycemic control ensures lower probability of adherence and success. As point 3 of our review states:

Point 3. The benefits of dietary carbohydrate restriction do not require weight loss.

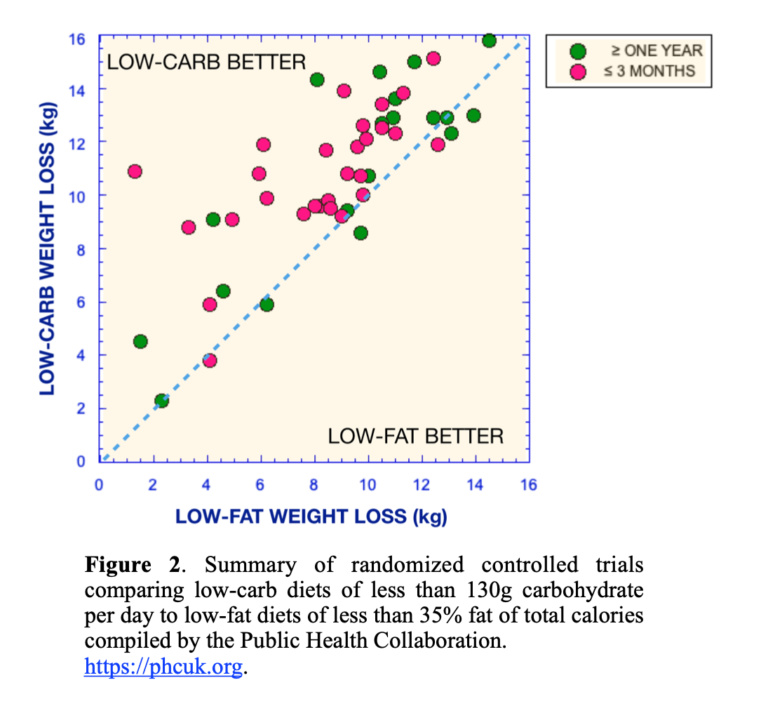

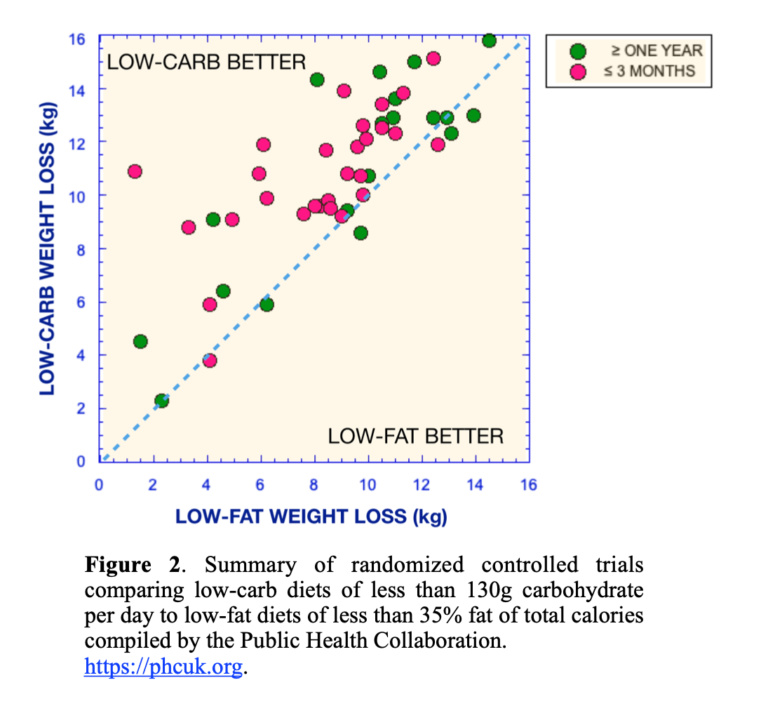

Weight loss protocols are usually designed to restrict calories across the board, which, because they usually start from high-carbohydrate baselines, de facto leads to reductions in carbohydrate. In any case, while the mechanisms are hotly debated, experimentally, low-carbohydrate diets almost always outperform low-fat diets, the usual alternative. A tabulation of RCTs in which the low-carbohydrate arm was under 35% of calories was published by the Public Health Coalition (Figure 2).

The mantra of nutritional medicine is that low-carbohydrate diets are better than low-fat diets in the short term but they are the same at one year. In a professional boxing title match, in the case of a draw, the champion maintains his crown. It is doubtful whether the low-fat diet is any kind of champion, but in fact, Figure 2 shows the argument against the low-carb diet is incorrect: While low-carbohydrate arm diets do better in the short term, they also do better after one year. The explanation of why this is not always seen is obvious and occasionally even stated explicitly. Adherence decays because of the looseness of the experiment protocol and the inability to monitor patient performance. The continuous care intervention of Hallberg et al., which takes advantage of telemedicine and personal counseling, dramatically increases persistent results, although there is some reduction in effects. Nonetheless, increasing adherence brings out the superiority of carbohydrate restriction. The principle, from point 4 in our review, is still:

Point 4. Although weight loss is not required for benefit, no dietary intervention is better than carbohydrate restriction for weight loss.

The ADA Vs. Science

“Low‑carbohydrate diets might seem to be a logical approach to lowering postprandial [after a meal] glucose,” said the American Diabetes Association (ADA) in a 2008 position statement (4). The comment was not meant as a guide to action. The statement continued: “However, foods that contain carbohydrate are important sources of energy, fiber, vitamins, and minerals and are important in dietary palatability. Therefore, these foods are important components of the diet for individuals with diabetes.” The confusion of carbohydrate, the nutrient, with foods that contain carbohydrate is deceptive and, in fact, odd in that energy is what the ADA always wants us to reduce. In any case, it is not just postprandial glucose. Improvement continues as long as dietary carbohydrate is kept low, which is perhaps why carbohydrate restriction, historically, was the recommended diet before the discovery of insulin.

Despite continued demonstrations of the expected efficacy of carbohydrate restriction, the 2018 ADA Standards of Care (5) indicated:

… a variety of eating patterns are acceptable for the management of diabetes (51, 53). The Mediterranean (54, 55), Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) (56–58), and plant-based diets (59, 60) are all examples of healthful eating patterns …

The references the ADA cited were to summaries or reviews, but these did not include our 12 points of evidence review (1) or the “eating patterns” directly targeting blood glucose. Nor did the list include any low-carbohydrate or ketogenic approaches. There is no real explanation for this bizarre fear of carbohydrate restriction, but it remains widespread. The ADA holds unique responsibility for discouraging people from carbohydrate restriction, though the practice is pervasive. The Mayo Clinic, for example, offers the following recommendation:

Contrary to popular perception, there’s no specific diabetes diet. However, it’s important to center your diet around:

-

- Fewer calories

- Fewer refined carbohydrates, especially sweets

- Fewer foods containing saturated fats

- More vegetables and fruits

- More foods with fiber

A registered dietitian can help you put together a meal plan that fits your health goals, food preferences and lifestyle. He or she can also teach you how to monitor your carbohydrate intake and let you know about how many carbohydrates you need to eat with your meals and snacks to keep your blood sugar levels more stable.

Targeting sweets and “refined” carbohydrates is considered a step forward.

The ADA in 2019 and the Looming Dietary Guidelines

The ADA’s guidelines for 2019 received approbation for offering low-carbohydrate diets as one of the options (6). Some of us were not impressed. We found it scientifically inaccurate, rife with ambiguous language, intellectually lacking, tedious, repetitive, and full of empty, trivial statements. And, of course, there was no explanation as to what was wrong before. Hallberg and colleagues provided their own perspective on the lack of rigor (7), but there are numerous concerns. For instance, the guidelines claimed:

For people with type 2 diabetes or prediabetes, low-carbohydrate eating plans show potential to improve glycemia and lipid outcomes for up to 1 year (62–64, 86–89).

“Potential” is inaccurate and dishonest. Point 1 applies: Dietary carbohydrate restriction has the greatest effect on decreasing blood glucose levels.

Despite their inadequacy, like much current medical writing, the consensus statement in the ADA’s 2019 guidelines is self-congratulatory:

The authors of this report were chosen following a national call for experts to ensure diversity of the members both in professional interest and cultural background, including a person living with diabetes who served as a patient advocate.

And despite all this expertise:

An outside market research company was used to conduct the literature search and was paid using ADA funds.

Whose Diet Is This?

The 12 points of evidence in our review (1) made the case for carbohydrate restriction as the thing to try first. We were clear that the data were “proposed as the most well-established, least controversial results.” We continued: “We feel that these points are sufficiently strong that the burden of proof rests on critics. The points are, in any case, intended to serve as the basis for improved communication on this topic among researchers in the field, the medical community, and the organizations creating dietary guidelines.”

Oddly, although the ADA did not identify us by name, the 2019 guidelines seemed to have assumed there was somebody out there trying to insist on their own way of doing things and this somebody did not understand that different people might have different needs. The intro to the 2019 consensus statement (6), in its typically verbose way, pointed out:

Evidence suggests that there is not an ideal percentage of calories from carbohydrate, protein, and fat for all people with or at risk for diabetes; therefore, macronutrient distribution should be based on individualized assessment of current eating patterns, preferences, and metabolic goals. (my emphasis)

It is not clear that evidence can suggest there is not an ideal, only that the ideal hasn’t been found, but again, nobody claims there is an ideal amount of carbohydrates. The word “individualized” appears 18 times in the consensus report (6), simultaneously suggesting there are autocrats out there and relieving the ADA from making real recommendations. In fact, however, the novelty of Hallberg et al. (2, 3) lies in that it:

… utilizes continuous care through intensive, digitally enabled support including telemedicine access to a medical provider (physician or nurse practitioner), health coaching, nutrition and behavior change education and individualized care plans, biometric feedback, and peer support via an online community. (my emphasis)

With Hallberg et al.’s continuous care intervention:

Participants were provided individualized nutrition recommendations that allowed them to achieve and sustain nutritional ketosis with a goal of 0.5–3.0 mmol L-1 blood BHB. Participants were encouraged to report daily hunger, cravings, energy, and mood on a four-point Likert scale. These ratings and BHB (beta-hydroxybutyrate) concentrations were utilized to adjust nutritional guidance. (my emphasis)

Where Are We Now?

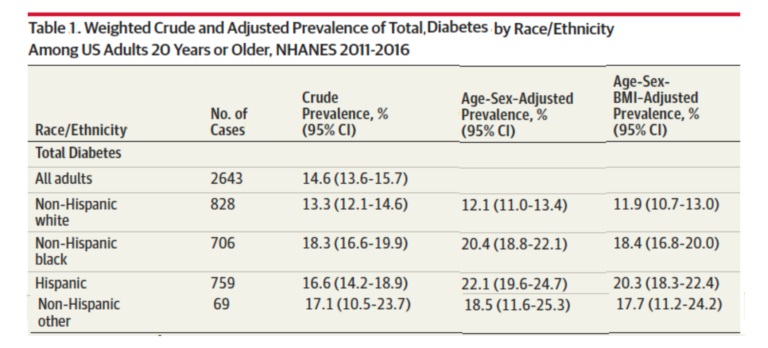

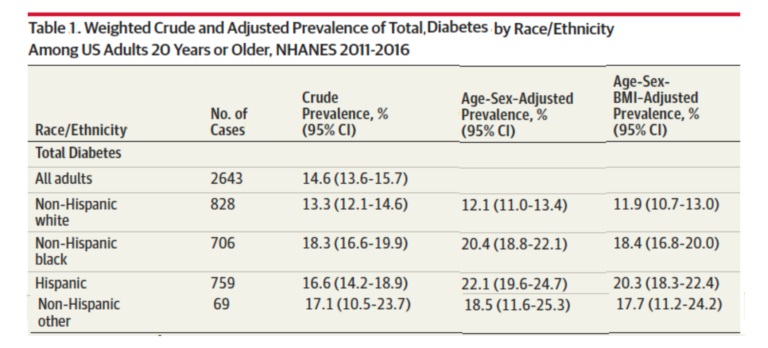

According to the Dec. 24 issue of JAMA (8), total diabetes (combined Types 1 and 2, diagnosed and undiagnosed (HbA1c > 6.5 %)) in the United States rests in the range of 14-22%, with significant differences based on race and ethnicity (Table 1 from reference 8). While described as an epidemic, the severity of the diseases appears to remain underappreciated, and public concern elicits nowhere near the same level of public response as diseases from infective agents (e.g., HIV or SARS).

Political pressure for reduction in the cost of drugs appears frequently, and there is particular outrage at the idea that people could die by virtue of not being able to afford insulin. While the drugs have varying degrees of efficacy, lip service at least is given to the importance of controlling dietary carbohydrate and, as noted above, proscriptions against sugar and “refined” carbohydrate are not likely to be useful if fear of fat prevails.

In the end, patients are on their own. Private and government health agencies continue to hold substantial power and, in some sense, the 12 points of evidence might be said to constitute articles of impeachment. Whether those in power will meet their critics remains to be seen.

Additional Reading

Richard David Feinman, Ph.D., is a professor of cell biology at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn, where he has been a pioneer in incorporating nutrition into the biochemistry curriculum. A graduate of the University of Rochester and the University of Oregon, Dr. Feinman has published numerous scientific and popular papers. He is the founder and former co-editor-in-chief (2004–2009) of the journal Nutrition & Metabolism. He is currently researching the application of ketogenic diets to cancer.

Richard David Feinman, Ph.D., is a professor of cell biology at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn, where he has been a pioneer in incorporating nutrition into the biochemistry curriculum. A graduate of the University of Rochester and the University of Oregon, Dr. Feinman has published numerous scientific and popular papers. He is the founder and former co-editor-in-chief (2004–2009) of the journal Nutrition & Metabolism. He is currently researching the application of ketogenic diets to cancer.

References

- Feinman RD, Pogozelski WK, Astrup A, et al. Dietary carbohydrate restriction as the first approach in diabetes management: critical review and evidence base. Nutrition 31(2015):1–13.

- Hallberg, S.J., McKenzie, A.L., Williams, P.T. et al. Effectiveness and Safety of a Novel Care Model for the Management of Type 2 Diabetes at 1 Year: An Open-Label, Non-Randomized, Controlled Study. Diabetes Ther. 9(2018): 583–612

- Athinarayanan SJ, Adams RN, Hallberg SJ, et al. Long-term effects of a novel continuous remote care intervention including nutritional ketosis for the management of Type 2 diabetes: A 2-year non-randomized clinical trial. Front. Endocrinol. 10(2019): 348.

- American Diabetes Association. Nutrition recommendations and interventions for diabetes – 2008. Diabetes Care 31. Suppl 1(2008): S61-S78.

- American Diabetes Association. Chapter 4. Lifestyle management: Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2018. Diabetes Care 41. Suppl. 1(2018): S38–S50.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes. Chapter 5: Lifestyle management. Diabetes Care 42(2019): S46-S60.

- Hallberg SJ, Dockter NE, Kushner JA, Athinarayanan SJ. Improving the scientific rigour of nutritional recommendations for adults with type 2 diabetes: A comprehensive review of the American Diabetes Association guideline-recommended eating patterns. Diabetes Obes Metab. 21(2019): 1769–1779.

- Cheng YL, Kanaya AM, Araneta MRG, et al. Prevalence of diabetes by race and ethnicity in the United States, 2011-2016. JAMA 322.24(Dec. 24, 2019): 2389-2398.

Richard David Feinman, Ph.D., is a professor of cell biology at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn, where he has been a pioneer in incorporating nutrition into the biochemistry curriculum. A graduate of the University of Rochester and the University of Oregon, Dr. Feinman has published numerous scientific and popular papers. He is the founder and former co-editor-in-chief (2004–2009) of the journal Nutrition & Metabolism. He is currently researching the application of ketogenic diets to cancer.

Richard David Feinman, Ph.D., is a professor of cell biology at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn, where he has been a pioneer in incorporating nutrition into the biochemistry curriculum. A graduate of the University of Rochester and the University of Oregon, Dr. Feinman has published numerous scientific and popular papers. He is the founder and former co-editor-in-chief (2004–2009) of the journal Nutrition & Metabolism. He is currently researching the application of ketogenic diets to cancer.