In this 2018 review, Valter Longo et al. discuss the current evidence supporting the use of fasting and/or fasting-mimicking diets in cancer therapy.

A fasting-mimicking diet (FMD) is a three- to five-day diet of water, vegetable broths, soups, juices, bars, herbal teas, and supplements. The diet is designed to drive a metabolic response similar to starvation without requiring a water fast. In healthy subjects, the FMD leads to significant reductions in insulin and glucose levels, IGF-1, and leptin, as well as increased adiponectin and ketone levels. A minimum of 48 hours of fasting or FMD is required to achieve clinically meaningful effects, and the FMD allows these effects to be achieved more consistently than true fasting, which involves greater risk and a reduced probability of compliance. In healthy subjects, five-day FMD cycles are well-tolerated; preliminary feasibility studies in self-selected cancer patients suggest they do not induce any significant side effects and may improve quality of life.

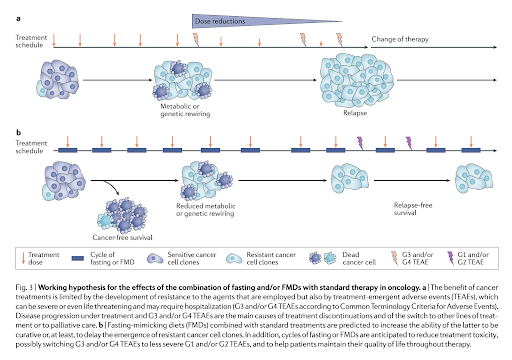

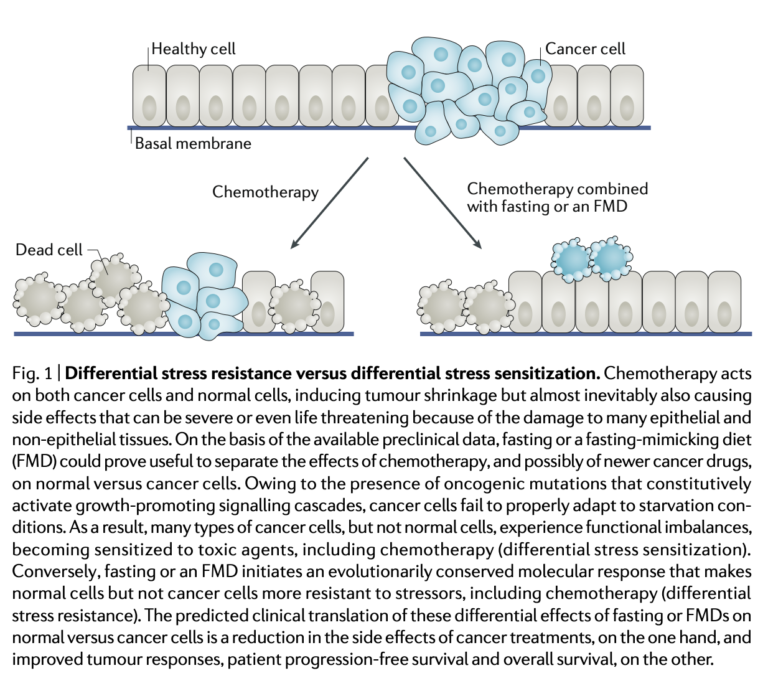

An FMD is unlikely to have a significant impact on cancer progression as a sole or primary therapy but may increase the effectiveness of other therapies when delivered simultaneously. The proposed general mechanism for this change is the differential stress response triggered by an FMD (see Figure 1 below). The FMD leads to a variety of metabolic changes (many downstream of the reduced IGF-1 activity it causes) that slow ribosome biogenesis and other proliferative activities within healthy cells, changes that increase cells’ resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs. Cancer cells, due to consistent deficiencies in their metabolic function, are unable to respond in this way and in fact often upregulate a variety of proliferative genes in response to fasting or an FMD. Reduced blood glucose availability also drives cancer cells to shift from aerobic glycolysis (as noted in the Warburg effect) to mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, which increases oxidative stress. Taken together, these effects simultaneously increase the impact of chemotherapy and radiotherapy on cancer cells and decrease their impact on healthy cells. Human data showing these effects is limited, but a variety of preclinical mouse studies collectively show that fasting and FMDs can potentiate chemotherapeutic damage and reduce tumor growth in mouse cancer models.

Figure 1