Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, or BDNF, is a group of proteins that plays a crucial role in nervous system function, development, and upkeep (1). Multiple lines of research have linked impairments in metabolic health to decreased levels of BDNF and vice versa, leading some to describe BDNF as a “metabotropin” (2). The relationship between BDNF and metabolic impairment seems to be bidirectional. Mouse studies have shown that artificially lowering BDNF levels leads to increased food intake and obesity (3), while BDNF infusions in humans have been tested to reduce body weight and improve glucose control (4). Individuals with diabetes and the metabolic syndrome, as well as those eating diets high in both fat and carbohydrate, have lower BDNF levels than healthy controls (5). Exercise and caloric restriction have independently been shown to increase BDNF, and with it, some measures of cognitive function (6).

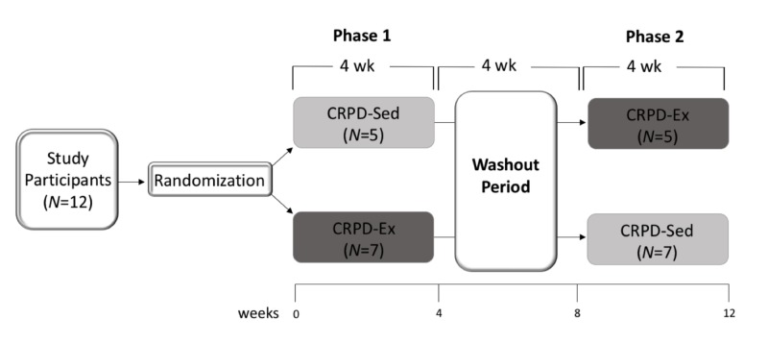

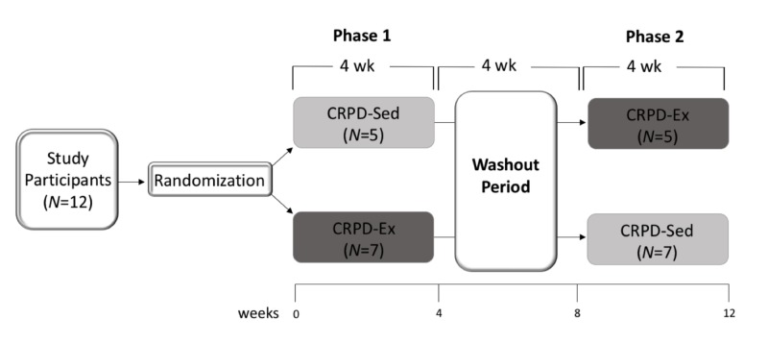

This trial tested specifically whether the beneficial effects of diet and exercise on BDNF and other measures of cognitive function are additive in metabolically unhealthy individuals. Four men and eight women (mean age: 40.9) were recruited, all of whom had metabolic syndrome. Subjects were placed on two four-week interventions in random order, separated by a four-week washout period. In both phases, subjects followed a low-carbohydrate paleolithic diet, which discouraged processed foods, dairy, and most grains and emphasized meat, certain vegetables, fruit, and nuts while limiting total carbohydrate intake to less than 50 grams per day. Subjects were not told to deliberately change total calorie intake. In one phase, subjects were told to remain sedentary. In the other phase, they were placed on a HIIT (high-intensity interval training) regimen that involved 10 60-second cycling bouts with 60 seconds of rest between rounds. The exercise aimed for approximately 90% maximal heart rate and occurred three days each week.

Figure 1: Trial design schematic

Subjects were compliant with the prescribed diet, reporting significant reductions in carbohydrate and total calorie intake (7). The reporting was supported by moderately elevated ketone levels in all subjects. Calorie intake decreased by approximately 800 calories per day from baseline, which is similar to what has been observed in previous studies testing carbohydrate-restricted diets in free-living subjects (8).

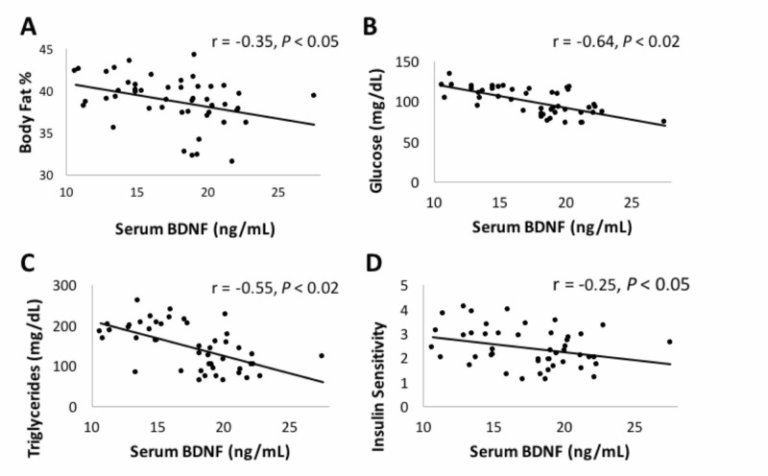

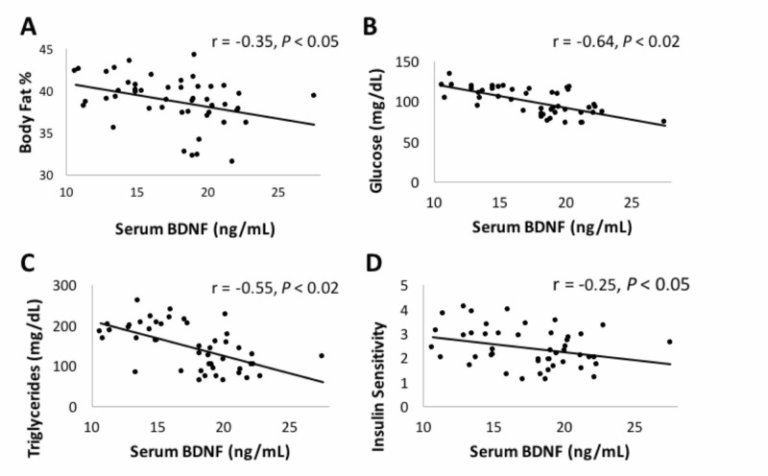

Both interventions led to significant increases in BDNF compared to baseline. The addition of HIIT led to significantly greater BDNF elevations than a change in diet alone (38% and 20% increases from baseline for the HIIT and sedentary interventions, respectively). Similar effects were seen in other measures of cognitive function, with both arms improving cognitive speed and flexibility (as assessed by Stroop test) as well as cognitive function (as assessed by MOS-CFS). Again, the diet-plus-HIIT intervention led to significantly greater changes than diet alone. Subjects showed improvements in body fat, fasting glucose, fasting triglycerides, and insulin sensitivity as a result of these interventions, and the degree of improvement in these metabolic measures was weakly, but significantly, correlated with changes in serum BDNF. This suggests carbohydrate and/or calorie restriction and high-intensity exercise have significant and additive beneficial effects on multiple measures of cognitive function and performance. Note, however, that because subjects significantly decreased the number of calories they consumed, this study cannot determine to what extent carbohydrate restriction or calorie restriction specifically affects BDNF levels.

Figure 2: Changes in multiple metabolic markers were correlated with changes in serum BDNF levels.

Previous studies have indicated caloric restriction improves BDNF levels and a variety of measures of cognitive function (9). Exercise alone has been shown to improve cognitive function, potentially via beneficial effects on BDNF levels (10). These effects have been shown to be intensity-dependent, with higher-intensity exercise leading to greater improvements. This may be due to direct links between muscular contraction and increased BDNF levels (11). The cognitive impairments observed in individuals with insulin resistance and/or the metabolic syndrome may be similarly mediated by reduced BDNF levels in these individuals, which suggests the metabolic improvements seen in these subjects may have directly influenced their BDNF levels (12).

Overall, these results indicate both diet and exercise lead to significant improvements in cognitive function and performance in metabolically unhealthy individuals. Previous research consistent with these results suggests the specific intervention used here — a combination of carbohydrate and calorie restriction alongside high-intensity exercise — may be maximally effective in improving cognitive function and performance.