Being able to teach a movement effectively revolves around two main elements: knowledge and communication. As a starting point, a coach should know the movement’s primary points of performance, the musculature involved, potential faults, and corrective strategies for those faults. However, being knowledgeable (or even a great athlete) does not ensure you will be effective at teaching a movement to others, because at the end of the day, coaches need to be able to communicate effectively with their athletes.

A great coach knows how to take their large body of knowledge and distill that down into simple and understandable teaching points, which brings us to our second component of effective teaching: communication. In my own experience as a coach, I have many examples of how I failed to do this.

In the Beginning

In my initial days of coaching, I used a lot of complex terms and would over-explain points of the movement to a level where my athletes were bored, overwhelmed, and confused as to what they were expected to do. As a matter of fact, the first time I taught the push jerk to someone, they left ‚— and never came back again! This helped me realize I needed to change my way of teaching. Simply being knowledgeable about the movement was not enough.

CrossFit Affiliate Summit – CrossFit Advantage – 10/17/2021

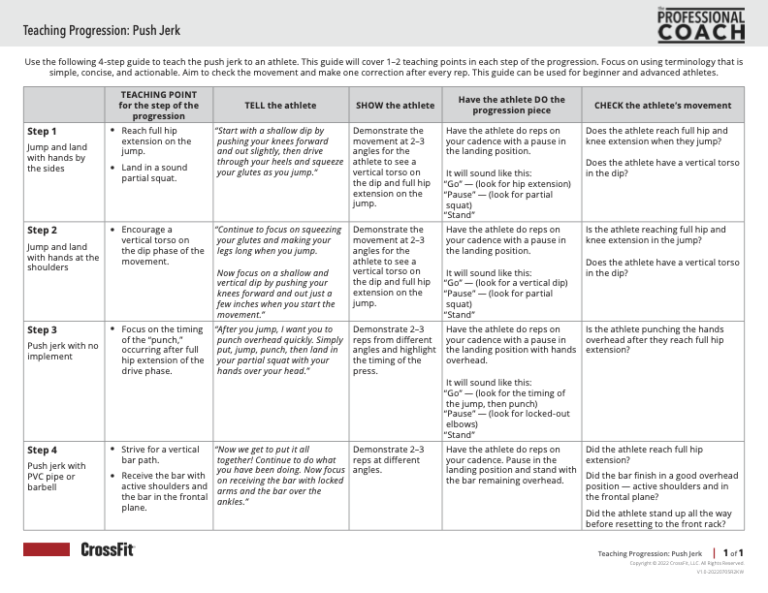

At my CrossFit Level 2 Certificate course, I learned a teaching progression for the push jerk. It involved having athletes start by jumping and landing with their hands by their sides, then jumping and landing with their hands on their shoulders, followed by doing a push jerk with no implement, and finally doing a push jerk with the PVC pipe or empty barbell. I initially scoffed at this progression as it seemed too simple. However, when I gave it a shot with my clients, I was shocked as to how well this progression got them performing the movement.

Finding Success in a Progression

My experience with the push-jerk progression changed the way I started to teach all movements to athletes. I started focusing on creating three- to five-step plans that covered one or two points at a time and progressed to the full movement while using terminology that was simple, concise, and actionable. With each step, I would focus on maintaining a habit of telling athletes what I wanted them to do, demonstrating it, having them do the movement, and then checking their movement to assess mechanics (tell-show-do-check).

Here is a breakdown of this in action with the aforementioned push-jerk progression that includes the important teaching components of each phase of the progression. Print out this sheet and use it as a resource when teaching athletes. You can use this same structure to create a progression to teach any movement.