Are overhead lifts dangerous for the shoulders?

Overhead lifts are challenging, not dangerous.

Efficient overhead lifts depend on muscular patterns that follow the “core-to-extremity” progression to optimize energy transfer from large to small body segments, and improve thoracic mobility.

Contrary to persistent myths about the risks of overhead lifting for the shoulder joints, studies and clinical observations show that, when performed with proper technique, overhead movements are safe and desirable for functional shoulder development. The overhead press, for example, is widely used in injury rehabilitation because it involves both anterior and posterior musculature, promoting joint balance and stability. Furthermore, moving in the scapular plane (between abduction and flexion) allows greater joint freedom and reduces the risk of mechanical impingement.

The Shoulders: The Role of the Scapula

The shoulder is not a single joint. It’s a complex structure made of five bones (clavicle, humerus, sternum, scapula + acromion), multiple muscles (rhomboids, teres muscles, infraspinatus, and trapezius), and four coordinated joints (sternoclavicular joint, scapulothoracic joint, acromioclavicular joint, and glenohumeral joint), which is why “shoulder complex” is the more accurate term. Highly mobile yet dependent on stability, it demands careful control, especially in overhead positions.

Dynamic stability comes from the coordinated work of stabilizing and mobilizing muscles. As the arm rises, the scapula (connected to the humeral head) must rotate and position precisely relative to the humerus. This scapulohumeral rhythm is driven by the serratus anterior and all portions of the trapezius, which rotate the scapula upward during abduction. That upward movement, along with a shrug, maintains subacromial space and promotes safe elevation.

The rhomboids and serratus anterior keep the scapula anchored to the rib cage, while thoracic extension from the spinal erectors aligns the trunk and arms. Biomechanically, the scapula’s role is to transfer and dissipate forces efficiently from the trunk to the arm.

For the overhead lift to work well:

- Serratus anterior and trapezius rotate the scapula upward, creating the subacromial space.

- Rhomboids and serratus anterior keep the scapula anchored to the rib cage.

- Adequate thoracic extension aligns the trunk and upper limbs.

Ensuring Safe External Rotation

When your athletes’ arms are overhead, teach them to externally rotate their shoulders while shrugging. If you see the elbows pointing forward, cueing athletes to point their armpits forward and to lower their elbows slightly works well and creates more subacromial space, protecting the tissues in the area. Otherwise, the athlete may experience pain due to a condition called subacromial impingement. Some symptoms include pain in the top arc of elevation or reduced overhead range of motion, especially when the athlete elevates the arm with internal rotation or a narrow grip. Visible compensation might look like excessive trunk lean or early elbow flare. If shoulder impingement symptoms persist even with rotation, you can test corrections with external rotation cues (“armpits forward”) or by having them widen their grip, which can help reduce the shoulder abduction angle and decrease the chance of humeral head-acromion contact.

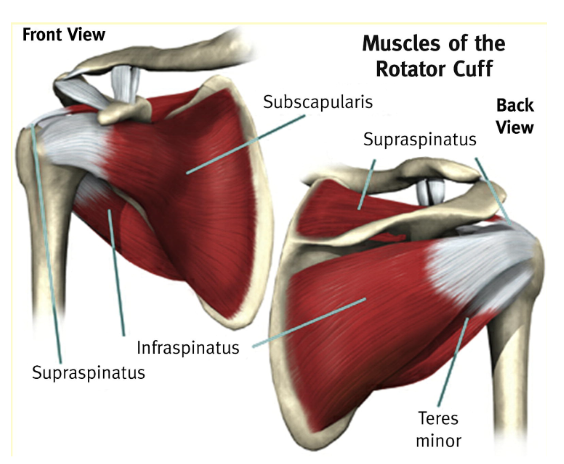

Additionally, to maintain a strong, stable overhead position with external rotation, the rotator cuff muscles (subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor) are critical for centering the humeral head and acting as active stabilizers to prevent joint translation. Scapular strength and control directly influence external and internal rotation mechanics because correct glenoid alignment preserves the optimal length-tension relationship of the rotator cuff.

Quick hits:

- Cue armpits forward, elbows slightly down

- Cue wider grip if there’s shoulder discomfort, specifically for the OHS

- If you see an early shrug, it may indicate poor serratus activation. Add some scapular push-ups to the warm-up.

- Promote a strong rotator cuff by keeping the humeral head centered. Rotator-cuff strength is developed through controlled external and internal rotation exercises, scapular-stability training (wall slides, serratus punches, Y-raises, T-raises), and progression to functional overhead stability drills such as landmine presses or Turkish get-ups. The key is gradual load progression and maintaining proper shoulder mechanics.

- Strong serratus muscles help to maintain the scapula working in harmony with the humerus. A good exercise for this is the floor-based scapular push-up.

Fixing the “Immature Trunk” on the OHS

According to the CrossFit Level 1 Training Guide, the overhead squat demands as much from midline control, stability, and balance as the clean and snatch do for power: the biomechanics require the load to remain aligned with the body’s frontal plane. When the bar drifts forward, the load on the hips and lumbar spine increases, compromising movement integrity and raising the risk of technical failure.

Conversely, athletes with an immature trunk will struggle to keep the bar aligned with the frontal plane. Limited ankle mobility (which restricts the knees’ ability to move forward) may be the underlying issue in this position. You will notice that the bar remains in the frontal plane, but at the cost of creating distance between the bar and the head and shoulders. This position can increase stress on the shoulders due to the increased torque. It may be worthwhile to perform an ankle screening test to assess mobility restrictions. From a half-kneeling position, with toes of the front foot 4.5 in (women) to 5.5 in (men) from the wall, attempt to push the front knee into contact with the wall without lifting the heel. If successful on both sides, mobility is unlikely to be the issue. If limited, add dorsiflexion drills.

The OHS requires greater core demand than the back extension or front squat, highlighting the trunk musculature’s stabilizing role. The trunk must resist the tendency to lean forward under load, requiring deep control from the spinal erectors, obliques, and transverse abdominis.

Unlike traditional floor-based abdominal exercises, the OHS develops upright postural control in a way that mirrors the demands of many other sports, making it superior for training deep trunk musculature because it provides a more functional and transferable stimulus.

Quick Tips To Improve Overhead Lifts

Given the technical and biomechanical demands of overhead lifts, a systematic approach to strength and mobility work is recommended. Priorities include:

- Rotator cuff strengthening, emphasizing exercises that promote glenohumeral stability and dynamic joint control. Use movements for external rotation (in multiple planes) and elevation in the scapular plane. These exercises can be incorporated into a warm-up or cool-down.

- Posterior shoulder capsule stretching is often associated with mobility restrictions that impair proper humeral positioning. Apply techniques such as the sleeper stretch and PVC pipe stretches.

- Thoracic and scapular mobility are essential for achieving a stable and safe overhead bar position. Lack of thoracic extension is a significant cause of technical failure in overhead lifts. The inability to achieve overhead arm positions with 180° of shoulder flexion is an indicator of limited thoracic mobility and/or restrictions in scapulohumeral rhythm. Look for rib flare or excessive lumbar extension, which can also be a helpful cue. Some exercises can be included in the warm-up or cool-down, such as foam-roller thoracic rotation, PVC pass-throughs, cat-cow, open book, or a lat stretch on the rig.

Without sufficient mobility, athletes may compensate by hyperextending the lumbar spine or forward-projecting the head. These limitations can be linked to tightness in the pectoralis minor or latissimus dorsi, and mobilizing these muscles can help achieve the ideal overhead position.

Conclusion

The overhead lifts are powerful tools for developing functional strength, joint mobility, and motor control. However, it requires precise technical preparation and attention to mechanics. Building adequate strength and mobility, reinforcing the shoulder complex, and regularly assessing thoracic and glenohumeral mobility form the foundation for safe, effective practice of these exercises.

Finally, it’s worth emphasizing that, contrary to some misconceptions, overhead movements are safe and beneficial when executed correctly. Overhead lifting contributes to greater mobility and a lower incidence of shoulder pain or injury, debunking the direct association between overhead movement and subacromial impingement. We encourage all of our athletes to learn and practice these movements, applying the concept of mechanics, consistency, and intensity to develop functionality and health.

In your next class, spend five minutes assessing your athletes’ overhead position and applying one of the corrections above. Minor adjustments can lead to significant improvements in stability and performance.