During the safety brief before a flight departs the runway, there is always a line to the effect of “put your own mask on first before helping those around you.” I always smile at the elegance of that instruction and its appropriateness as a framework for developing virtuosity in coaching.

Although perhaps not intended to be, that line is wonderful life advice. It is such a natural human instinct to want to help others, but our best intentions are entirely undermined if we haven’t first sorted out our own health and fitness. The harsh truth is that a coach will be somewhat useless in improving others if they can’t improve themselves first. I would go so far as to say that the mess the fitness industry found itself in before CrossFit was primarily due to a culture of trainers and coaches failing to “walk the walk.”

CrossFit brought sanity to the fitness industry by challenging the theoretical and embracing only what worked in practice. We understand you learn by doing and that firsthand experience is the pathway to virtuosity. Only when you “put your own mask on first” can you truly understand how to coach others. There is no room to be a theoretical coach within CrossFit; you must lead by example.

2005, Nicole Carroll, and the Zone

I have been doing CrossFit since 2005, and although there have been many lightbulb moments that have improved my life, the paradigm shift in nutrition was by far the most profound.

Like many, I started CrossFit by throwing myself into the workouts and ignoring what I was eating. In those early days, I had no understanding of the profundity of the statement “nutrition is the foundation of the pyramid.” I mirrored the same flawed approach as I started training clients, pouring heart and soul into teaching movement and driving intensity with little regard for changing their nutrition habits. Initially, my clients and I found improved fitness despite ignoring nutrition — everyone gets a honeymoon period, but soon, improvements started to plateau.

In the wise words of strength coach Dan John:

“Everything works … for about six weeks.”

In 2007, Nicole Carroll challenged me to do the Zone diet for at least six weeks and then retest my workout performance. At the time, I thought I had a good understanding of the Zone, but it was a theoretical understanding based only on what I had read. Despite not having tried it, I arrogantly thought I knew enough about it to think it wouldn’t work for me. This is a common mistake made by coaches: the tendency to eliminate things before trying them. My most significant error in thinking was that the Zone Diet, and weighing and measuring in general, was just for people who wanted to lose weight. Nicole motivated me to do the Zone by telling me that my performance would improve — and she knew it would because she had done it herself. So I agreed to do it to prove her wrong.

After six weeks, I had to eat humble pie.

My performance on some pre-selected benchmarks had improved dramatically. I had significantly more energy. Perhaps the most surprising finding was that weighing and measuring was more straightforward than I thought. This was the beginning of the realization that nutrition is vital and that there are many subtleties and nuances to coaching that can only be realized through firsthand experience.

The Zone diet became a staple for me and those I coached from then on. That experience also spurred me to look to nutrition as the primary intervention I needed to focus on when people entered the gym. I had unlocked a big piece of the puzzle: The ability to positively influence nutrition habits was the driver for success — inside and outside the gym. Whenever a client struggled to make progress, nutrition became the area to focus on first.

Since that first Zone challenge, I have probably weighed and measured my food at least twice a year for at least 30 days. And before every nutrition challenge I ran at my gym, I completed the challenge myself to collect data. This is a critical part of my coaching confidence. By doing what I preach, I have confidence that what I prescribe works. It also gives me great insight into the emotional experience and a road map for potential implementation pitfalls.

2021, the Rise of Apps, and the 30-Day Challenge

In 2021, we released the CrossFit Nutrition I Course. The Zone diet is no longer the recommendation (although we do accommodate it for those like myself who have a strong preference for it), but the underlying principles have remained the same: Eat meat and vegetables, nuts and seeds, some fruit, little starch, and no sugar in quantities that support exercise but not body fat.

And now we have apps that make implementing our recommendations and adhering to the foundational principles that CrossFit has always taught — eat real food (quality) and match your intake to your needs (quantity) — even easier.

In the course, we also provide many more options for people to scale into our recommendations. We know that individualizing the approach is essential. And we know that weighing and measuring are done on a continuum for each individual, from all the time to a few times a year to a one-time experience. Despite this, the course is still consistent with our belief in quality and quantity, and at a deep level, not much has changed.

A key recommendation in the course is that everyone undertake a 30-day challenge to put the theory into practice. This challenge consists of eating quality food only and weighing and measuring intake. If I still had my 2007 coaching mindset, I would think this challenge only applied to my clients. After all, I am fit and don’t need to lose weight. I already know the content in the Nutrition I Course intimately. I played a role in creating the course, and given the hours I have spent immersed in the content creation, I think I could almost recite the Training Guide from memory. Surely I get a pass, right? Not at all. I have learned the lesson Nicole taught me very well. So, as soon as the course was complete — and before it launched — I had to do the challenge to experience it firsthand. There is no other way to lead as a coach.

Now, let me take you through what I did and what I learned.

3, 2, 1 … go!

My challenge started by working out how much and what to eat. Even though I had done this many times before, I resisted the temptation to default to what I had done previously with the Zone diet. This is important because I wanted to test the nutrition course precisely as it is written. I also wanted to embrace the learning experience and understand the similarities and differences between our current recommendation and what I have done before.

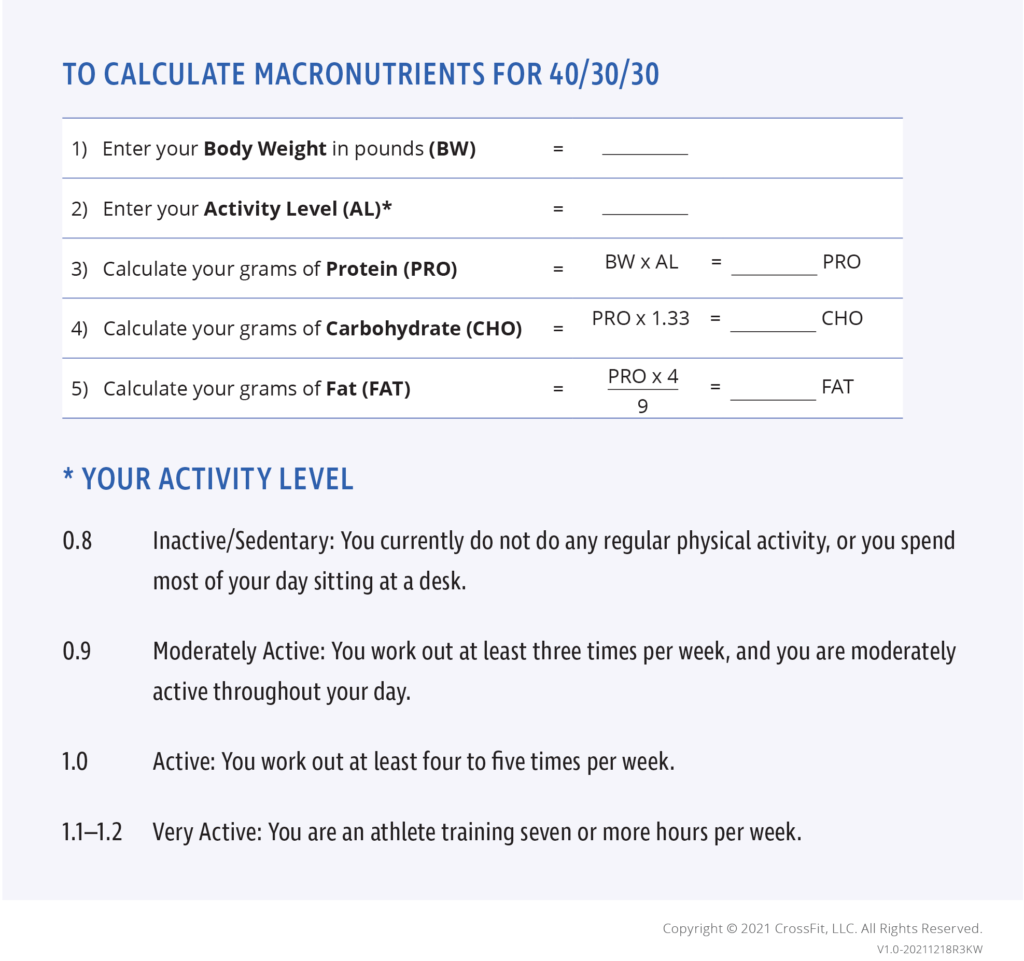

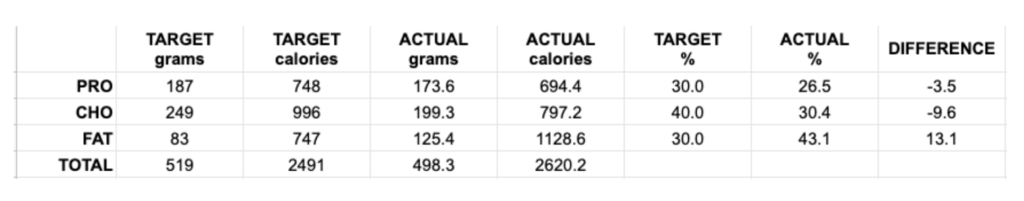

The reality of human nature is that we tend to hide behind what we already know; therefore, trying new things has to be a conscious and determined effort. So, instead of calculating Zone blocks, I followed the new process outlined in the course to the letter. Using the formula provided, I set my goal weight at 187 lb (85 kg) and used that to calculate my protein, carbohydrate, and fat ratios. Then, based on a 30 P/40 C/30 F ratio as a starting point and allowing 1 g of protein per lb of body weight based on being active, my target macronutrients worked out to 187 g of protein, 249 g of carbohydrate, and 83 g of fat per day. This equated to 2,491 calories per day.

As an interesting comparison, previously I would have started with 18 blocks on the Zone diet, which would have worked out to:

- 126 g of protein (compared to 187 g)

- 162 g of carbohydrate (compared to 248 g)

- 54 g of fat (compared to 83 g)

- for a total of 1,638 calories (compared to 2,491 calories)

Part of this discrepancy is that there are hidden calories in Zone blocks that aren’t accounted for, but also due to the history of the Zone diet and its role in addressing metabolic disease, the diet was calorie restrictive by design and intentionally created a deficit. This is why an athlete on the Zone diet doubles and triples fat once they lean out too much. There are not enough calories prescribed to account for the activity levels of CrossFit athletes who follow the Zone diet, so fat blocks were increased to make up the caloric deficit and keep insulin resistance in check. This is an interesting discovery, but the critical point is that this only became clear to me as a coach through my personal experience with both diets. Once again, I learned by doing.

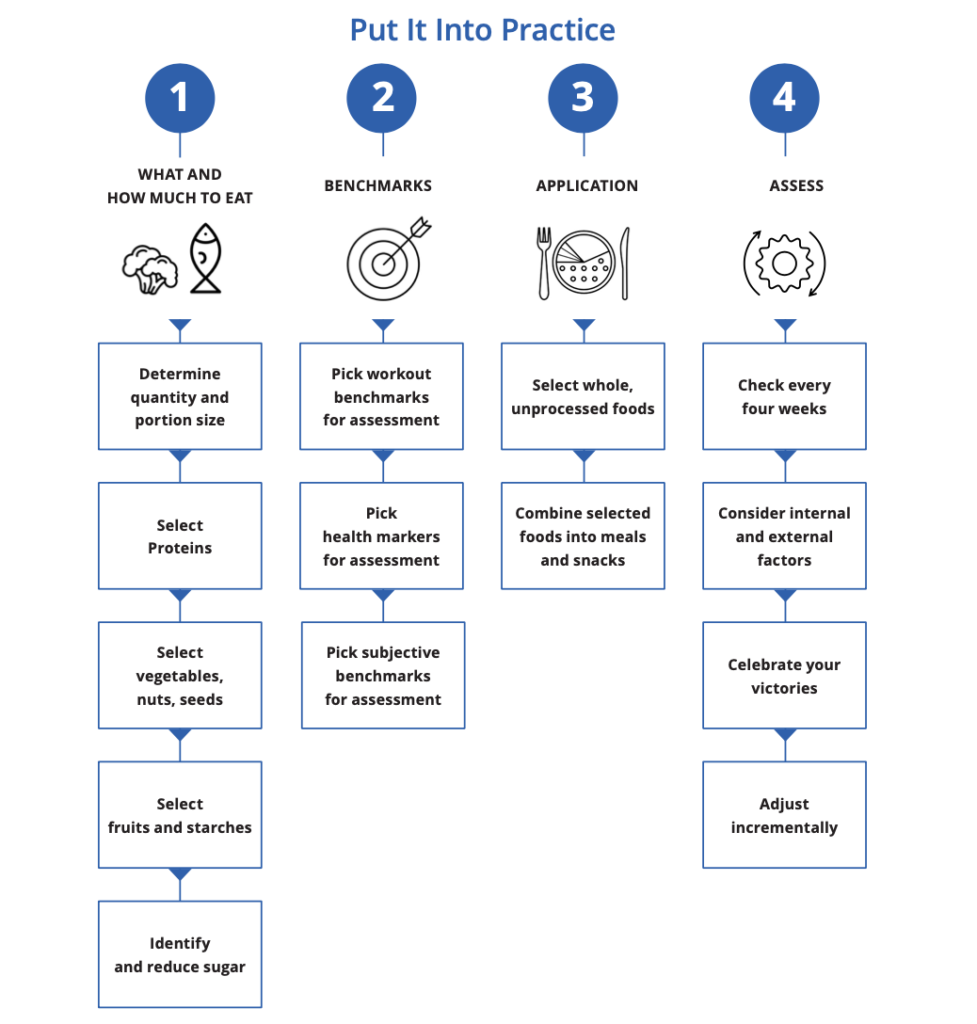

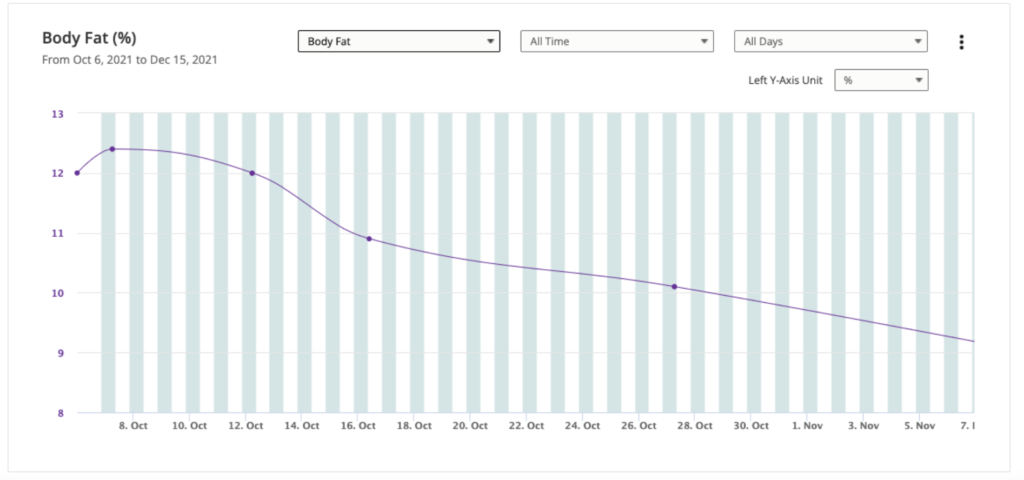

Once I determined what and how much to eat, I decided on some basic benchmarks to measure my improvement. First, I chose two physiological markers — body weight and body-fat percentage. Since retiring from CrossFit competition in 2018, both of these have drifted up, so one outcome I was hoping for was to bring them down to match where they were when I was competing. In addition to these two, I chose a modified version of a workout from crossfit.com that was cardiovascularly demanding and in which skill was not a limiting factor: 3 rounds for time of a 15-calorie row, 12 dumbbell snatches (32 kg), and 9 burpees (modified slightly from a barbell power snatch to a dumbbell snatch). This is a workout in which improvement comes from having the energy to push harder. So I decided to keep it very simple, and mostly I was interested in my general feeling of well-being and energy level, which are subjective markers. If I were doing this challenge with a client, I would include additional clinical markers (such as triglycerides and blood pressure) and a balance of workout benchmarks as per what we recommend in the Nutrition I course.

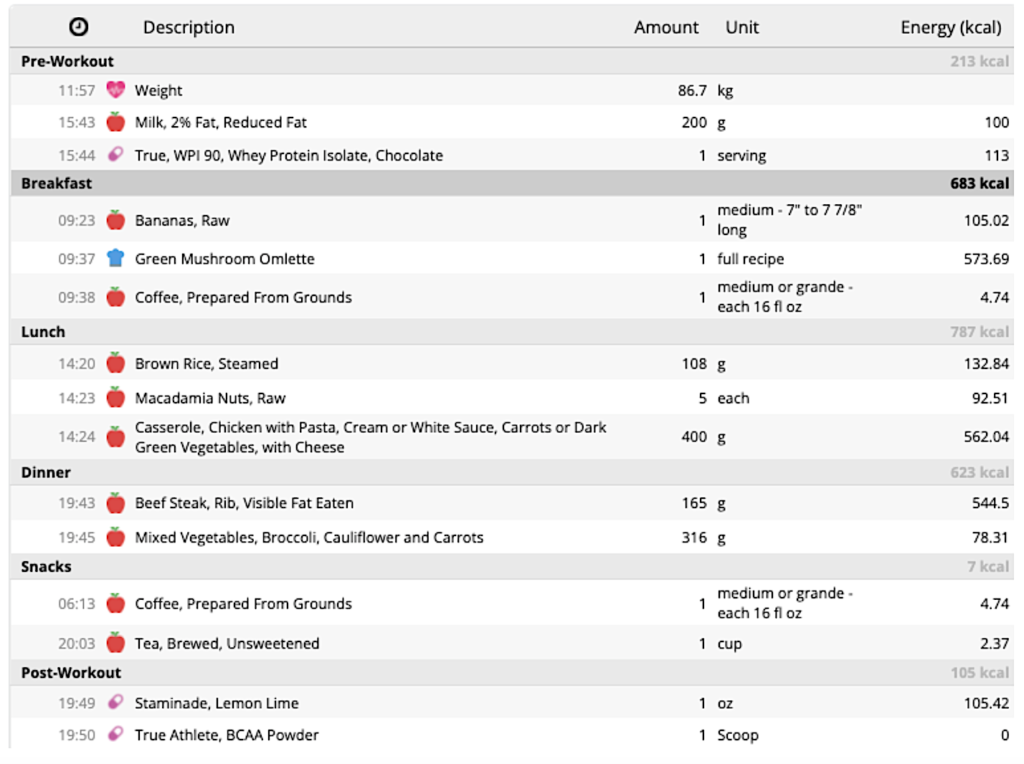

Once I had my benchmarks set, I followed the process in the course for meal planning. I settled on three main meals, one snack, a small pre-workout meal, and a post-workout meal. A typical day looked like this:

In addition to weighing and measuring my macros, I also decided to test the intermittent-fasting protocol we recommend. I signed on to a 12-hour fast every day. Based on what was most manageable with my lifestyle and career, my fasting window would be from 9 p.m. to 9 a.m. Working remotely on U.S. time, I usually start work around 4 a.m., so this fasting window meant I could clear all of my morning meetings and then enjoy breakfast. Then, to track my intake, I settled on an app called Cronometer.

I blew the dust off my kitchen scales, committed to 30 days of weighing and measuring everything I ate, and set about building meal options and recipes. I planned to balance every meal according to a 30 P/40 C/30 F ratio with an overarching goal of hitting my macronutrient targets at the end of each day. Most importantly, I also committed to eating only real food in line with the starting point in the course. This didn’t require much change because I have followed “meat, vegetables, nuts and seeds, some fruit, and no sugar” for a long time now. I don’t drink alcohol, and even when I am eating poorly, I am mostly avoiding processed food. I tend to overeat quality food rather than processed food. Because of this, it was easy for me to commit to quality and quantity in the challenge and be precise with weighing and measuring. I can throw myself hard at a challenge like this without worrying about it setting me up for failure. This approach, however, may be way too much for anyone who is not eating well to start with. For the average client, starting with just a quality-based challenge and then dialing in quantity in a second challenge could make more sense and align with our general recommendations.

30 Days: Leaner, Healthier, Fitter

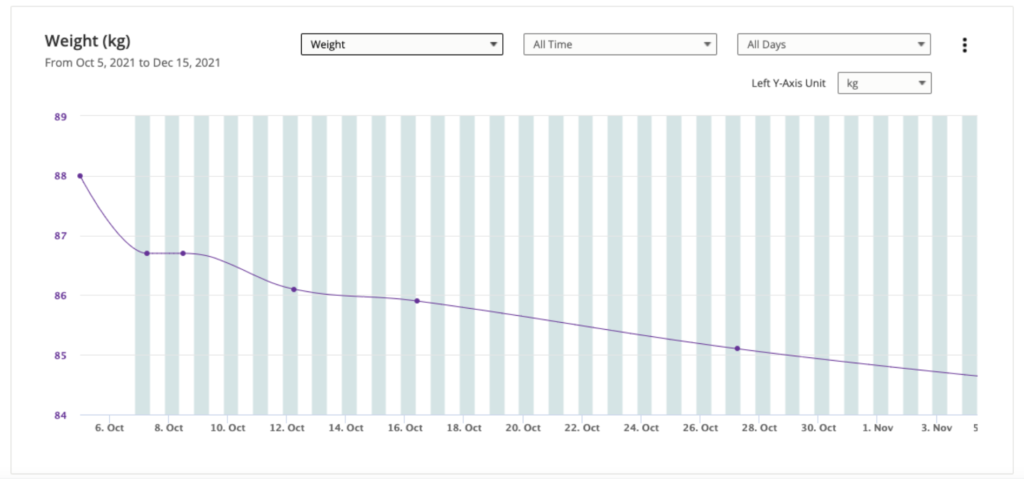

I pulled the trigger on Oct. 5, didn’t miss a day, and was 100% compliant. This is what happened:

I was astounded by three things I couldn’t have predicted:

- The rate at which I leaned out was dramatic and significantly faster than what I had experienced on the Zone diet, yet I wasn’t in any significant calorie deficit.

- I didn’t experience any cravings in the first two weeks, which had been my previous experience on the Zone diet every time I dialed it in.

- Using the app made the whole process straightforward, and it didn’t require very much willpower.

Overall, the results after a month were well beyond my expectations. My performance on the benchmark workout improved by 35 seconds and felt a lot easier, my body weight dropped from 88 kg to 84 kg, and my body fat dropped from 12.4% to 9.1%. Within a week and a half, I started to feel energized, and most noticeable was that I found myself wanting to work out more.

Although I initially set out to experience the course firsthand, I came away from the challenge very pleased with the physical changes I experienced. Yet again, a short bout of eating quality food and managing quantities precisely had dialed my health and fitness back to where they should be. But, most importantly, I now had direct evidence that what we recommend works.

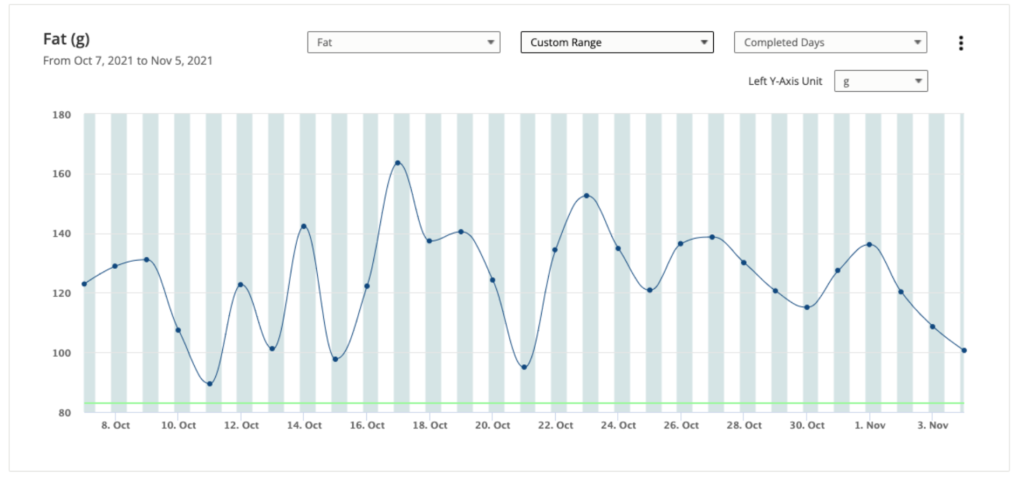

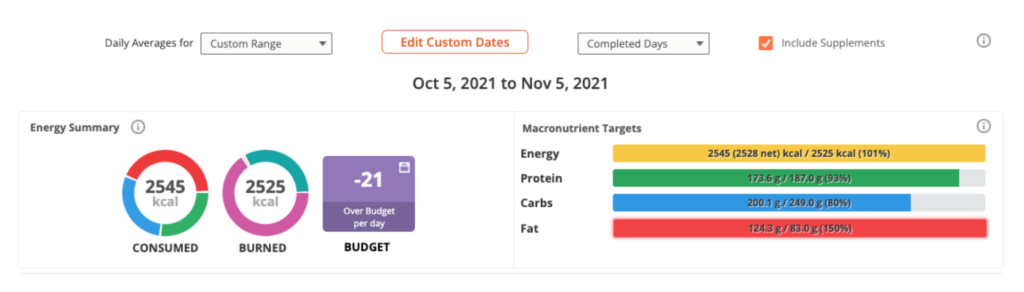

There were also some surprising coaching lessons. First of all, I found it very hard to get my protein and carbohydrate levels to the daily target without feeling like I was overeating, and I didn’t realize the degree to which I was using fat to make up for the carbohydrate shortfall. This was something I would not have picked up on if I weren’t using an app to track intake. I ended up making adjustments to my macronutrient ratios based on what felt balanced for each meal rather than being a slave to the starting ratio. This experience was a good reminder that our recommended ratios are simply a starting point, and individual experimentation is key to finding what works in practice. This is what my intake ended up looking like after 30 days:

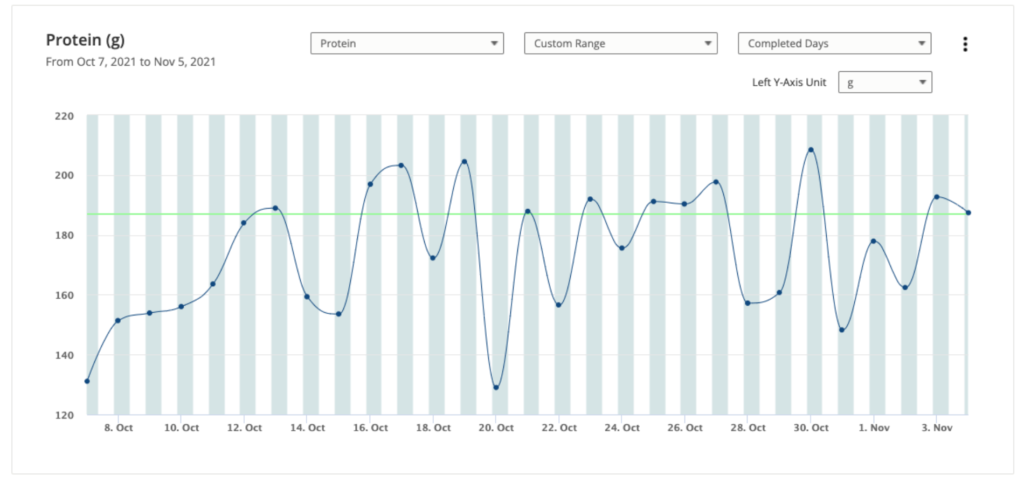

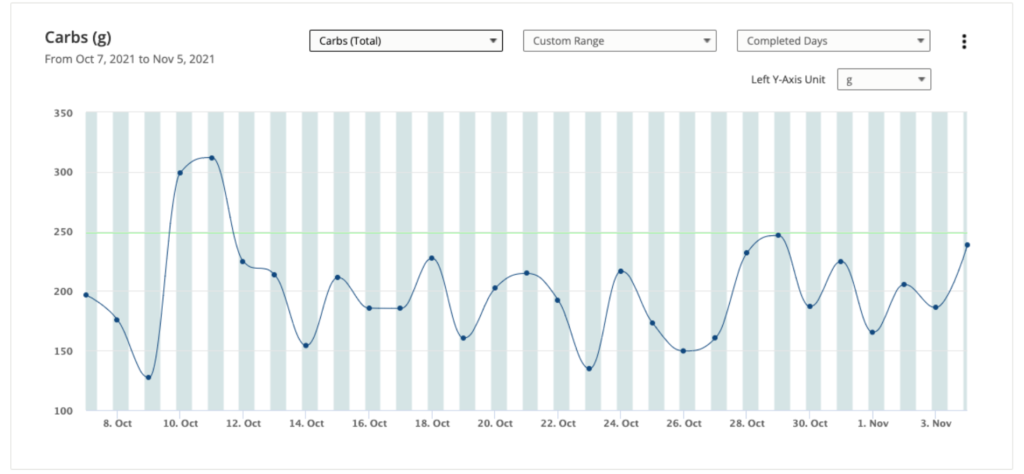

This is the variability in actual intake of the three macronutrients, even though I was working hard to try to keep it consistent each day: