On May 24, 2010, my wife drove me to our family doctor’s office and told me not to emerge without a diagnosis. Over the previous two or so months, I’d started to feel increasingly thirsty, and I’d not only started to drink water all day but I’d also started to pee all day. And all night. I was losing weight, my muscles were wasting away in a strange crackling ache, and I felt tired all the time. I even woke in the mornings feeling tired.

Since I am a doctor and a metabolic biochemist, I did what any doctor and metabolic biochemist would have done under those circumstances: I ignored the symptoms in the hope they’d go away. But my wife, who didn’t know better, drove me to the doctor’s office with orders not to emerge without a diagnosis.

Everybody reading this will have guessed my diagnosis, of course, and indeed my urine was full of sugar, as was my fasting blood (350 mg/dL; normal fasting range below 100), while my HbA1c was 13.3% (normal range below 5.7%). Once diagnosed, however, I was prescribed the usual drugs, to which my blood sugar levels responded appropriately, and all seemed well — until I was sent to the dietitians.

In those dark days, back in May 2010, Type 2 diabetics like me were given three pieces of dietary advice:

- We were told to eat frequently, at least five times a day. Breakfast was a particularly important meal.

- We were told to eat carbohydrates and avoid fat. Sugar was also to be avoided, but complex carbohydrates like porridge (oatmeal) or brown bread or potatoes or brown rice were very healthful.

- Alcohol was to be avoided.

I shall not address the whole gamut of this advice, for CrossFit has been in the forefront of exposing much of it, but I shall tell the story of breakfast; for after my condition had settled down, and after I’d adopted my newly recommended diabetic diet, I soon — thanks to my glucometer — made a dismaying observation. Well, two observations actually.

First, I was waking with quite high blood glucose levels of around 135 mg/dL. Those levels, I was to discover, were typical of Type 2 diabetics. But when I ate the breakfast I’d been recommended (porridge, aka oatmeal, without sugar or milk), my blood sugar levels rapidly spiked to over 200 mg/dL, which could only damage me. In short, the advice I’d been given was bizarre, for I was being told to eat carbohydrates on top of a high baseline blood sugar level. Even worse, I was being told to eat carbohydrates in the morning, which is the time of maximal insulin and glucose resistance.

We wake in the mornings because blood levels of cortisol spike. This spike wakes us up, but it also makes us insulin- and glucose-resistant. And since Type 2 diabetes can be described as a condition of insulin and glucose resistance, the advice I’d received to eat carbohydrates at a time of maximal insulin and glucose resistance can really be described only as weird. Were the doctors and dietitians actually conspiring against their patients?

Breakfast has a recorded history of over 3,000 years. The ancient Greeks ate breakfast (in both the Iliad and the Odyssey, Odysseus eats breakfast) as did the Romans, and from the surviving records we know that, in classical times, people breakfasted on bread, cheese, olives, nuts, raisins and polenta porridge. During the medieval period in Europe, though, members of the upper classes stopped eating breakfast. The peasants, needing to fuel their work in the fields, ate on rising in the mornings, so, to highlight their freedom from manual labor, smart people in that era of feudal class divisions would ostentatiously not eat until lunchtime. Today’s fashion for time-restricted eating (eating only lunch and dinner) has, therefore, a long and posh pedigree.

Breakfast made its social revival only after the breakdown of the feudal system, during the 16th and 17th centuries, when even smart people needed to engage with markets, which was hungry work. But as, during the 20th century, life became increasingly sedentary for people, they tended to revert to the old aristocratic pattern of eating less in the mornings. By the 1920s, the average American breakfast amounted to little more than a cup of coffee and perhaps a roll or a glass of orange juice, which concerned the cereal, bacon, and egg companies.

Breakfast has, over the millennia, generally been a light meal because many (not all, but many) people are simply not hungry in the mornings (in book 19 of the Iliad, Achilles, a breakfast-skipper, wants to attack Troy first thing in the morning; it’s Odysseus who insists on breakfasting first). This lack of morning hunger is probably an evolutionary defense against eating when insulin and glucose resistant, but whatever the reason, it has obviously impacted negatively on investors in the food industry, who have done everything they can to overcome it.

So, during the 1920s, the Beech-Nut Packing Company (a bacon producer) paid the leading PR operative of the day, Edward Bernays (Sigmund Freud’s nephew and the author of the 1928 book Propaganda, which was Joseph Goebbels’ bible), to mobilize 4,500 doctors to endorse big breakfasts (a later film by Bernays describing his persuading the doctors to endorse breakfast is still available on the web). But Bernays was pushing at an open door, because everybody “knew” breakfast was the most important meal of the day. And everybody “knew” we should breakfast like kings, lunch like princes, and dine like paupers.

The “discovery” that breakfast was the most important meal of the day was made in 1847 by Dr. William Robertson, who practiced medicine in Buxton, in the U.K., and who wrote in his Treatise on Diet and Regimen: “Breakfast should always be an important, if not the most important, meal of the day.” Why? Well, because “breakfast is very properly made to consist of a considerable proportion of liquids, to supply the loss of the fluids of the body during the hours of sleep.” Eh?

Robertson, you see, was a water physician, and Buxton was a water spa town, and Robertson believed Buxton waters could cure a host of diseases, including the terrible problem of night-time dehydration. This was a belief not far removed from Hippocrates’ belief in the four humors; or, to put it less politely, it’s garbage.

It is to Adelle Davis (1904-1974), an American dietitian, that we owe the mantra that we should eat breakfast like a king, lunch like a prince, and dine like a pauper. Why? Well Davis, who was no more scientific than Robertson, had been told that our blood sugar levels fall in the mornings unless we eat breakfast. Actually, nothing could be more healthful in the Western world today than falling blood sugar levels, for over half of all older people are pre-diabetic or Type 2 diabetic. But Davis supposed (with precisely zero evidence) that falling blood sugar levels were a problem, to which breakfast was the solution. We now, therefore, know the evidence Davis invoked to justify breakfast actually shows the opposite: To be healthy in a world of rampant Type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes, we should skip breakfast and rejoice in our blood sugar levels falling gently yet safely over the morning.

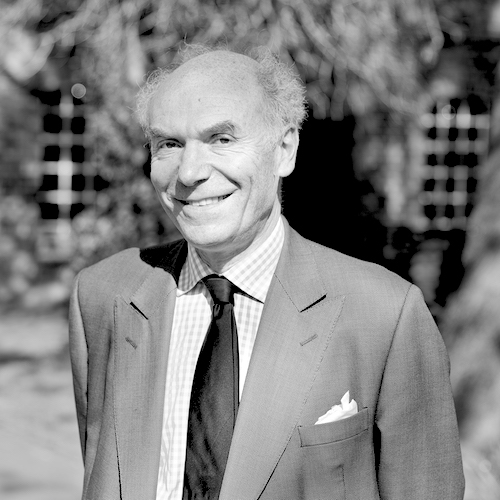

Terence Kealey was born in London, where he also went to medical school (Bart’s Hospital Medical School, University of London; in the U.K., most medical students start at the age of 18.) But he soon realized he wanted to do research, so after his house year (internship) he went to Oxford to do his D.Phil. (Ph.D.) in metabolism, where his supervisor (advisor) was Philip Randle. After some years at Oxford, he moved to Cambridge, where he lectured for many years in clinical biochemistry. He then moved as vice chancellor (president) to the University of Buckingham, which is the only university in the U.K. not to be funded directly by the state. After many years there, he moved to the Cato Institute in Washington, D.C., and though he has recently returned to the U.K., he remains an adjunct scholar at Cato.

Terence Kealey was born in London, where he also went to medical school (Bart’s Hospital Medical School, University of London; in the U.K., most medical students start at the age of 18.) But he soon realized he wanted to do research, so after his house year (internship) he went to Oxford to do his D.Phil. (Ph.D.) in metabolism, where his supervisor (advisor) was Philip Randle. After some years at Oxford, he moved to Cambridge, where he lectured for many years in clinical biochemistry. He then moved as vice chancellor (president) to the University of Buckingham, which is the only university in the U.K. not to be funded directly by the state. After many years there, he moved to the Cato Institute in Washington, D.C., and though he has recently returned to the U.K., he remains an adjunct scholar at Cato.

His research focused on the cell physiology of human skin (his group, for example, was the first to grow hair follicles, including human hair follicles, in vitro), but when, 10 years ago, he developed Type 2 diabetes, he resurrected his earlier training in biochemistry and medicine to show that the conventional clinical advice of the day for Type 2 diabetics was bizarre. In 2016 he published Breakfast Is a Dangerous Meal (4th Estate, London).