“You’ll never walk again.”

The neurologist’s declaration didn’t compute in Mary Lou Jensen’s mind. She’d been walking just fine a few days ago. A senior and retiree, she was more active than most people half her age. She did Pilates seven days a week and golfed six — and she hiked, biked, and danced with her husband in their free time.

The leg spasms started on Friday afternoon, Dec. 8, 2017.

“We went to Costco, and I felt like I was walking like a drunken sailor,” Jensen recalled.

When she awoke at 5 a.m. the next morning to use the bathroom, she had to crawl. A neighbor brought her to the emergency room, where she was checked for a stroke. All clear.

But around noon that day, she tried and failed to stand and walk. The diagnosis came one day later: neuromyelitis optica, a central-nervous-system disorder in which the immune system attacks cells in the optic nerves and spinal cord. It’s rare, its cause is largely unknown, and it can result in permanent blindness and/or paralysis.

In Jensen’s case, she was paralyzed from the second thoracic vertebra (T2) down.

“Walking one day and paralyzed the next,” she said.

No one would have blamed her had she accepted her paralysis as part of aging. She could always move into a nursing home.

“Oh my God, are you kidding?” Jensen said. “I don’t envision myself there at all. … That would’ve meant giving up and saying I’m old — I’m old, but I’m not that old that I don’t want to live my life.”

After a year of training with Joshua Nix (left), Mary Lou Jensen (right) had increased her core strength enough to squat with external loading.

“All We Do Is Fitness”

About six months after her diagnosis, Jensen rolled into Defiant Fitness with an attitude to match. The Minnetonka, Minnesota gym is home to CrossFit Hopkins and Fit 4 Recovery, an adaptive-fitness and neurological-rehabilitation program for individuals with neurological impairments. Owner Joshua Nix launched Fit 4 Recovery in early 2015 after the exercise-based rehabilitation center where he previously worked as a certified spinal-cord injury recovery specialist closed down.

Fit 4 Recovery is described as a program “focused on providing quality fitness-based training for adaptive athletes, individuals with neurological impairments, and anyone else who wants to get strong.” Nix and his training staff work with individuals of all ages and abilities, catering in particular to those with spinal-cord injuries, cerebral palsy, traumatic brain injuries, stroke, spina bifida, and more.

Fit 4 Recovery and CrossFit Hopkins athletes form one shared community at Defiant Fitness, regardless of ability.

But Nix isn’t just a spinal-cord injury specialist. A CrossFit Level 1 Trainer since 2012, Nix had dreamed for as long to open a CrossFit affiliate. So when his former employer closed its doors, he saw the perfect opportunity to meld his two passions: neuro-rehab work and functional fitness.

“It had so many parallels with what we do in CrossFit that I thought it would just make so much sense to combine the two under the same roof — the two communities will thrive together,” Nix said.

It took some time. Nix began by training his neuro-rehab clients on a yoga mat in the corner of the CrossFit gym where he’d been working as a part-time coach. Soon after, he moved to a 700-square-foot space in Eden Prairie, Minnesota, crammed with all manner of equipment: weights, parallettes, boxes, bands, barbells. In the mornings, Nix did CrossFit workouts there with his buddies before converting the tiny space into a rehab center, customizing its configuration for each Fit 4 Recovery client.

In 2020, Nix moved Fit 4 Recovery into the 5,000-square-foot space it calls home today, launching CrossFit Hopkins in the same space in January 2021.

“We have a small CrossFit community kind of built up and are starting to see the two worlds come together,” he said. “All we do is fitness, at the end of the day.”

Rewiring the Brain

So how exactly does neurological-rehabilitation-meets-CrossFit-training work? It’s all about neuroplasticity, or the brain’s ability to adapt on a neurological level to its environment and our own behavior; to literally change its structure in response to intrinsic and extrinsic factors. (Ever heard the term “muscle memory”? That’s neuroplasticity at work.)

In healthy individuals, neurons carry messages from the brain to the muscles via the spinal cord. Think of the nervous system like a highway connecting points A (the brain) and B (the muscle). Damage to the nervous system, be it a spinal-cord injury, traumatic brain injury, or other neurological condition, creates a roadblock on that highway.

“All of a sudden you have a 10-car pileup, and you have to navigate your way through that pileup — the signals don’t have a clear path through,” Nix said.

But as long as some signal remains, neuroplasticity makes it possible to chart a new path from point A to B. As it turns out, functional movement — especially when executed at high relative intensity — makes an excellent cartographer.

John Novicki sets a new 350-m row PR.

Much of the current research on how exercise affects the brain centers on cognitive disease and function. It’s been shown, for instance, that engaging in physical activity can reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia by 45% and 28%, respectively.

But exercise has also been shown to improve motor function — even a single session of aerobic activity can promote neuroplasticity in the motor cortex, the part of the brain in charge of planning, controlling, and initiating voluntary movement (in the study cited, a single session of aerobic activity lasted 15-30 minutes).

This isn’t news; physical rehabilitation has long been standard practice for individuals dealing with paralysis, full or partial. But less understood is how intensity affects neuroplasticity.

One animal study analyzed the effects of exercise intensity on dendrite complexity in rodents (dendrites are branch-like extensions with which neurons receive information from other cells). The study found “increased dendrite complexity” in rodents who ran on a treadmill, which has a greater musculoskeletal demand, compared with those who ran on wheels. And a 2017 study on humans with incomplete spinal cord injuries — those who retain some motor or sensory function below the point of injury — found that high-intensity training, indicated by heart rates at 70-85% of the subjects’ maximum heart rates, “elicited greater gains in selected locomotor performance and metabolic outcomes than low-intensity (locomotor training).”

As for Nix, he doesn’t have any studies to cite or data to prove that high-intensity exercise improves patient outcomes.

“I’m going off of my experience with my clients for that,” he said.

Intensity, as students of CrossFit know, is relative. The barbell weight one athlete requires to elicit “Fran cough” might be 50 lb more or less than another’s. But intensity among neuro-rehab patients can be even more nuanced. For many Fit 4 Recovery athletes, intensity is forged in the mind.

“You can have both mental intensity and physical intensity, and neuroplasticity is often triggered by higher-urgency focus,” Nix explained. This is not surprising, as high-focus mental states such as that of meditation have been shown to promote neuroplasticity and improve executive control, monitoring, and attentional processes.

“What I’m seeing is often while working with my clients, we have better results when the demand is such that it requires a maximum amount of focus,” Nix continued.

Raycer Frank works on assisted sit-ups with trainer Joshua Nix.

He compared Fran with a 1-rep-max snatch.

“Your intensity in Fran is extremely physical; you go into that pain cave and try to survive,” he said. Whereas with the snatch — “that visual that you run through before pulling the bar, the heightened focus as you (approach) the bar” — a lot of the intensity is between the ears.

“And I would say that’s similar for our clients with neurological impairment,” Nix said. “When it takes every ounce of your being to try to lift your arm up against gravity, that might be the intensity that we’re looking at.”

One way Nix helps his clients achieve that heightened state of focus is by taxing multiple areas of the body simultaneously, prioritizing “functional positions that allow us to work on increasing strength but also have a positive impact on range of motion and balance and coordination.”

Consider 17-year-old Raycer Frank. In April 2020, the International Series of Champions (ISOC) snocross champion suffered an injury to his C6 spinal vertebra during routine motocross practice. Though his spinal cord was not severed, doctors said it was unlikely he’d ever walk again.

Frank joined the Fit 4 Recovery program and began training with Nix in early 2021. And although he could not stand or walk, some evidence of signal — such as muscle twitches and spasms — remained in his adductors, hamstrings, and quads.

“Getting his body to do what we wanted was like trying to untangle a mess of tangled-up ropes,” Nix recalled.

Traditional therapy might have seen him do robot-assisted gait therapy. Nix taught him to crawl.

“Doing a lot of crawling work has helped to both build up his core strength as well as strengthen his hip flexors … which are tight and can restrict him from being able to stand upright,” Nix explained. “But then we’re also working on his shoulder health and range of motion throughout there as well as his balance and his proprioception.”

At the end of one July workout, Frank demonstrated another great intensity-generating combo: squats and pegboard ascents. With his legs strapped together at shoulder width and braced by foam padding at the front and a sandbag in the back, Frank gripped a notched peg in each hand, slowly pushing his hips back and down into Nix’s waiting hands.

With minimal assistance from Nix, Frank then used the pegs to pull himself up out of the squat, rising a little farther with every notch. After several reps, he swapped one peg out for a weighted version, alternating which arm took the heavier load.

The exercise looks a lot like a pull-up — or a transfer from Frank’s wheelchair to his truck.

“A lot of what we’re working on in here translates over to functional movements that my clients are going to have during their day but doing so in a way that taxes as many things as possible and gives us as much momentum as possible,” Nix said.

Squats and pegboard pull-ups help Raycer Frank build the strength he needs to get into his truck.

The training is beneficial even when it doesn’t look exactly like a client’s daily movements.

In 2015, Joe Hennen, now 34, hit his head after diving off a dock into a shallow lake. The C5-C6 motion segment in his neck fractured, resulting in a complete spinal-cord injury and permanent paralysis from the waist down.

But that doesn’t mean he skips leg day.

The first thing Hennen does when he trains is get out of his wheelchair. After he lies down on a pad, a trainer works Hennen’s legs, stretching and bending them and rotating and opening his hips and pelvis.

Why work muscles that don’t?

Although Hennen cannot voluntarily move his legs, enough neurological connection remains to cause spasticity, or involuntary muscle contractions. While not entirely a bad thing — spasticity means there’s some signal there — it can be painful. Working the spasms out in the gym helps increase flexibility and reduce muscle tightness.

Joe Hennen gets the “chair out of the body” with some seated row work.

In other words, it takes “the chair out of the body,” said trainer Mike Greenheck, borrowing a turn of phrase from Nix.

“When you’re seated, your hip flexors shorten as well as your hamstrings, and in turn, tightens certain things up and creates compression in the lower back,” Nix explained. “So working the chair out of the body is essentially elongating the tissue, counteracting the position that a lot of my clients are in a lot of the time, that seated position.”

“[That’s] really important even though he can’t use his legs in the way someone else can,” Greenheck continued.

Hennen agreed.

“When I get done, I almost can’t feel my body; it’s like a little relief,” he said. “All this helps so much with the circulation, nerve pain, and spasms and muscle tightness. It’s like that deep breath at the end. It feels great because I can’t feel anything.”

After they work out the leg spasms, Hennen and Greenheck focus on strengthening Hennen’s upper body. Leaning against an exercise ball and supported by his trainer, Hennen might work on rowing, pulling a weighted PVC pipe hooked to an elastic band. Then, he might strengthen his midline with some assisted sit-ups, gripping Greenheck’s hands and pulling himself up from a lying to a seated position.

The work has helped improve Hennen’s quality of life in ways many take for granted, such as when opening and closing doors or even adjusting his body position in bed or in his chair.

“It’s a mini Christmas,” he said of his weekly training sessions. “I love it.”

Once told she’d never walk again, Mary Lou Jensen drags 35 lb across the gym.

A Godsend

When Jensen started training with Nix, she was “just like a baby,” she said.

She lacked the core strength even to sit up in bed, her legs had become severely atrophied, and she’d dropped to a slight 104 lb at 5 foot 9.

Through a painstaking process of trial and error, fishing for neurological stimuli, and trying to get her body to “bite down” on even the tiniest signal, Jensen regained sensation. Then movement. Then strength — and she’s only gotten stronger.

Today, three and a half years after joining Fit 4 Recovery, Jensen can get in and out of bed independently. She can do weighted air squats. In July, she trekked several laps around the room at Defiant Fitness with the help of a walker, dragging a 35-lb plate leashed to her waist about 10 feet behind.

“I can walk a football field with my rollator,” she said.

Before joining Fit 4 Recovery, 67-year-old John Novicki, who has multiple sclerosis, could not cross his left ankle over his right knee.

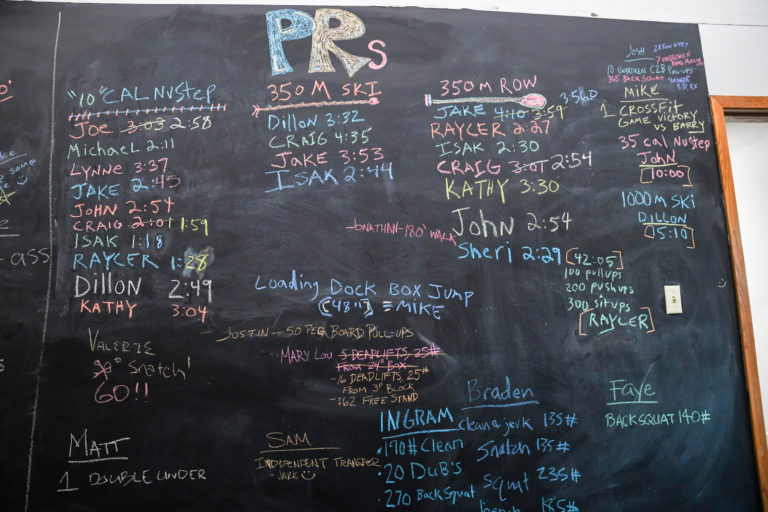

“I worked with Mike two times, and that became not an issue,” said Novicki, who also recently PR’d his 350-m row time at 2:44. “This has just been a godsend.”

As for Frank, while not yet fully recovered, he’s back on the track. And in that same summer pegboard training session, he crawled several laps of the room, did 35 sit-ups, and took his first steps on two feet since before his accident.

“If that’s not CrossFit, I don’t know what is,” Nix said.

Raycer Frank walks for the first time since his injury with support from the parallel bars.

All photos by Wendy Nielsen.

Comments on This Is Your Brain on CrossFit — How Functional Fitness and Intensity Improve Neural Function

5 Comments

Amazing - love what you are doing for people!

Simply fantastic work Josh, prayers for your continued success & your clients victories!

Wow.........

This is dope! Squatting with a pegboard is genius.

This is amazing and awesome!

(Wish I had the credentials to help people like this)