As previously noted in Part 1 of this series, my life changed at the end of June 1981 when I received a letter from a 46-year-old female runner of 108 lb. who had experienced never-before-described symptoms during the 56-mile Comrades Marathon.

She told me that late on the afternoon of June 1, 1981, she fell into a coma and was admitted to a hospital following her participation in that year’s marathon. Twelve miles from the finish, she failed to recognize her husband, who had come to assist her. He convinced her to stop running and drove her to the medical facility at the race finish. There, she received 2 liters of fluid, administered intravenously for treatment of “dehydration” that was then—and continues to be now—the expected cause of all complications that occur during prolonged exercise (1).

Her husband, noting that her condition worsened after she received the intravenous fluids, decided to take action. He wanted her to be admitted to a hospital in Durban, South Africa, where the race had started. But on the drive back to Durban, the runner suffered a grand mal epileptic seizure and lapsed into a coma. She was admitted to the hospital, where blood testing found her serum sodium concentration to be reduced to 115 mmol/L; a chest X-ray indicated the presence of “water in the lungs” (pulmonary oedema), confirming a diagnosis of exercise-associated hyponatremic encephalopathy (EAHE), the first such known case. Treated very conservatively, her serum sodium concentration returned to the normal range, and she regained consciousness on the fourth day in hospital. She was discharged from the hospital, fully recovered, a further two days later, six days after she had begun the Comrades Marathon in perfect health.

When this runner wrote to me, she asked, “What happened?” I answered that I had no idea but would investigate.

By 1985 we had made some progress in the investigation. We reported her story and another three similar cases in a paper entitled ‘‘Water intoxication: a possible complication of endurance exercise” (2). Even then, we observed (without direct measurement), “the etiology of the hyponatremia in these runners was due to overhydration.” We concluded with the admonition that “the intake of hypotonic fluids in excess of that required to balance sweat and urine losses may be hazardous in some individuals” (2).

The following year, two doctors who had developed EAHE during the Chicago 80/100-km ultramarathon described their experiences (3). Notably, these doctors had been advised to drink 300–360 mL at each aid station placed 1.6 km apart on the 10-km lap course on which the race was held. They also noted, “In addition, athletes are instructed to drink more than their thirst dictates, since thirst may be an unreliable index of fluid needs during exercise. Runners, as a group, are taught to ‘push fluids.’” As a result, each drank in excess of 20 liters of fluid during the eight to 10 hours they ran. The authors became aware of our earlier study only after their original manuscript had been accepted for publication. Their identical conclusions were developed independently of our own: “The two runners consumed such large quantities of free water during the race that apparent water intoxication developed. … It seems likely that the hyponatremia was caused primarily by increased intake and retention of water and contributed to the sodium loss.”

In a historic coincidence, the senior physician in that report received intravenous hypertonic (3%) saline for the treatment of his EAHE. His serum sodium concentration increased from 118 mmol/L to the normal range (135 mmol/L) within eight hours of hospital admission. He returned to his home in Atlanta the following morning, resuming his medical practice that same afternoon. But his junior colleague was less fortunate. Treated with the less concentrated, normal (0.9%) saline solution intravenously, he remained semi-comatose for 36 hours while his serum sodium concentration remained low. He was discharged from the hospital only on the fifth hospital day, four days later than his senior colleague.

Hence, the first “controlled” clinical trial comparing the effects of isotonic and hypertonic saline in the management of EAHE was completed, by chance, already in 1983 and reported in 1986, antedating by 22 years the conclusion that hypertonic (3-5%) saline solutions are the most appropriate therapy for this condition (4) and the use of less-concentrated saline solutions is absolutely contraindicated (5).

Thus, by 1986 a body of evidence showed:

(a) EAHE is caused by excessive fluid consumption during exercise;

(b) athletes who drink to excess during exercise usually do so on the well-meaning advice of others, including race organizers; and

(c) the condition responds hardly at all to treatment with 0.9% normal saline, whereas recovery is rapid when hypertonic (3–5%) saline solutions are used. It would take almost another 20 years before this wisdom would be universally applied (5).

After 1985, it became apparent to us that EAHE was becoming increasingly common in 56-mile Comrades Marathon runners. Sixteen athletes were admitted to the hospital with EAHE after the 1987 race. Accordingly, we decided to follow the fluid and sodium balance during recovery of all runners admitted to the hospital for the treatment of EAHE after the 1988 Comrades Marathon. We specifically hoped to determine whether the initial conclusions from the first case reports were correct.

The report of that study, published in 1991 (6), came to the following unambiguous conclusion:

This study conclusively resolves this issue (of what causes EAHE). It shows that each of eight athletes who collapsed with hyponatremia of exercise (mean plasma sodium concentration of 122.4 mmol/L) was fluid overloaded by an amount ranging from 1.22 to 5.92 liters. These fluid volumes are conservative because no allowance was made for insensible water losses during recovery. The subjects conservatively estimated that their fluid intakes during exercise ranged from 0.8 to 1.3 L/h, compared with maximum values of 0.6 L/h in normonatremic runners. We also found that the subjects’ sodium losses (153 mmol) were not larger than those of runners who maintained normonatremia during exercise.

Thus, it was concluded that “the hyponatremia of exercise results from fluid retention in subjects who ingest abnormally large fluid volumes during prolonged exercise.”

In our youthful naivety, we assumed this would be the end of the matter—that these definitive findings would be universally embraced and preventive actions based on our conclusions would be enacted immediately around the world, with the result that EAHE would disappear as quickly as it had emerged.

With minimum resources and little direct funding, including none from the sports drink industry, my colleague Dr. Dale (Benjamin) Speedy took up the challenge of testing our findings in a series of studies of New Zealand Ironman triathletes. Whereas we had been able to study just tens of athletes in competition, his team chose to study many hundreds. By applying simple but relevant measurements to large numbers of subjects in a series of groundbreaking studies, Dr. Speedy’s team confirmed that EAH and EAHE had become common in Ironman finishers; that female athletes are especially at risk; and that the cause is fluid retention from excessive fluid consumption during events lasting more than four hours (7-11).

What is more, his team was able to show that simply by (a) advising the athletes not to overdrink during competition and (b) restricting fluid availability during the cycling and running legs of the race, the number of cases of EAHE requiring hospital admission was reduced from 14 in the 1997 New Zealand Ironman to three the following year. There also was no evidence that this advice increased the number of athletes requiring medical care because they drank too little during exercise and had become “dangerously dehydrated.” Instead, as is usually found, the most “dehydrated” triathletes usually won these races.

Discovering the Cause of EAH and EAHE Did not Prevent an Increase in These Conditions in the U.S. Military in the 1990s

Just as these successes were occurring, the incidence of EAH and EAHE was increasing dramatically in the U.S. military, with 125 cases of EAHE requiring hospital admission between 1989 and 1996 (12). In addition, there were at least six recorded deaths (13-15).

Of these 125 cases, 40 occurred at a single training facility: Fort Benning in Georgia. Evaluation of these 40 cases showed, “(1) all were associated with excessive water intake; (2) the training cadre often mistook hyponatremia for dehydration, and; (3) afflicted trainees were not given (appropriate) medical care in a timely manner” (13).

Suitably alarmed, the U.S.military correctly concluded that the introduction of their novel drinking guidelines, as I described earlier (16), were at fault. As a result, revised guidelines were introduced in April 1998. These new guidelines set upper limits of fluid consumption at 1–1.5 quarts per hour (909–1364 mL/h) and 12 quarts (10.9 liters) per day. The impact was immediate. The incidence of hyponatremia in the U.S. Army fell in 1998 and 1999, with most of the reduction occurring as a result of the immediate adoption of these new guidelines at Fort Benning.

However, a report published in March 2018 (17) shows that cases of EAH and EAHE still are happening at Fort Benning. In the words of Maj. (Dr.) Meghan Galer:

In an effort to prevent heat stroke, we have this culture of drink water, drink water, drink water. But if you drink too much water, you basically dilute the electrolytes in your body, specifically the sodium. When that happens, fluid shifts in your body, specifically in your brain, and your brain swells, and because of your skull, it has nowhere to go. This condition is known has hyponatremia and can be caused by someone over-hydrating.

To prevent Emergency Medical Service (EMS) personnel from giving potentially life-threatening intravenous fluids to collapsed soldiers with EAH or EAHE, Galer added the crucial first step that we had proposed as the standard of care in 2005 (5): Specifically, before anyone who collapses during prolonged exercise (more than three hours) is given intravenous fluids, it is essential that their blood sodium concentration be measured to rule out EAH or EAHE. Galer insisted: “Our medics, or anyone at the scene, are not allowed to give more than one liter of ice-cold fluid until they know what the patient’s sodium is.” As a result, Fort Benning EMS personnel must now carry with them an iStat machine, which provides a real-time measurement of the patient’s blood-sodium concentration. It is worth noting that these Fort Benning changes also occurred in response to CrossFit’s hydration conference and its proposed strategies for avoiding EAH and EAHE.

Of course, a simpler precaution would be simply to prevent the condition from happening in the first place by telling the soldiers to “drink to thirst.” There has never been any evidence that drinking any amount of fluid—either too little or too much or just the right amount—prevents or causes heatstroke. In fact, we have reported the only known case in the world in which a soldier died from the combined effects of heatstroke and EAHE (18). Tragically, the overdrinking that caused this soldier’s EAHE did not prevent his fatal heatstroke.

The evidence that excessive fluid replacement cannot prevent heatstroke is reviewed fully in Waterlogged (19), first published in 2012.

The American College of Sports Medicine Ignores These Findings, With Predictable Outcomes

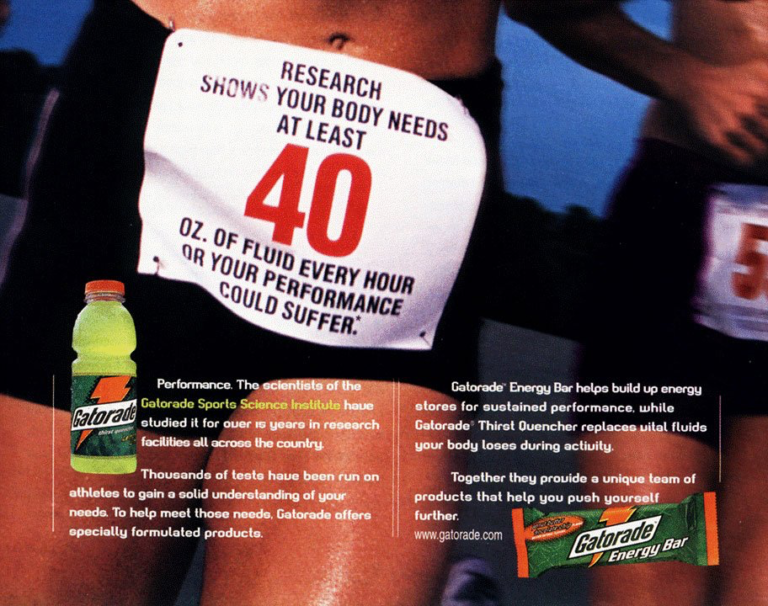

In 1996, the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM), an organization whose only two “platinum” sponsors at the time were Gatorade and the Gatorade Sports Science Institute (GSSI), produced its modified Position Stands, which promoted the concept that subjects should drink “as much as tolerable” during exercise (20, 21). This was linked to an extensive marketing campaign, directed by the sports drink industry through the GSSI (22), to promote this new advice.

d