Circadian rhythms are moderated by two “clocks.” The first clock is a “master clock” that responds to daily dark-light cycles, is regulated in the hypothalamus, and regulates various circadian processes in the rest of the body via neuronal and hormonal signals (1). The second clock responds to meal times, and in particular to regular patterns of feeding and fasting (2). This second clock can override the impact of the master clock on organs and tissues if mealtimes and the duration between meals are deliberately manipulated (3).

Disruptions to circadian rhythm have been linked to impaired glucose and lipid metabolism, cancer, the metabolic syndrome, and immune system dysfunction; restoration of circadian rhythm has been linked to the prevention of these same conditions (4). Studies in which mice have been fasted overnight (5) have triggered improvements in a variety of metabolic pathways (6). This April 2020 trial built upon this preliminary evidence by surveying the effect of fasting on a variety of proteins and other biomarkers in young, healthy adults.

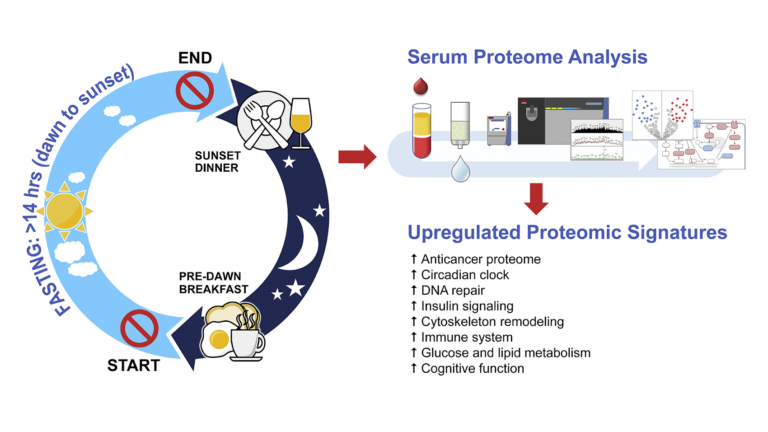

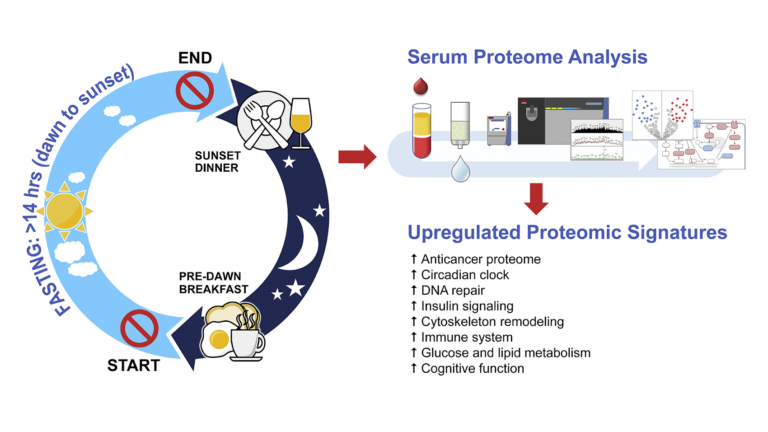

Fourteen subjects (13 men and 1 woman) free of chronic disease were recruited to follow a 30-day fasting program. Each day, fasting began after a pre-dawn breakfast and continued until a post-dusk dinner. In practice, this led to a daily fast exceeding 14 hours each day. Subjects ate their usual diets during non-fasting hours and were instructed to not reduce their total calorie intake. Proteomics were assessed prior to, immediately after, and one week after the fasting period.

Figure 1: An overview of the intervention

Fasting changed expression of a variety of proteins. Significantly, these changes included:

- Increased expression of LATS1, CFHR1, and COLEC10, all of which are downregulated in hepatic (liver) cancers (7);

- Reduced expression of RRBP1 and FM05, which are increased in colorectal cancers (8);

- Reduced expression of a variety of other proteins linked to increased cancer risk, including B4GALT1, ASAP1, TNSK2, HUWE1, ARHGEG28, PALB2, SMOC1, IRAk, and MUC20 (9);

- Increased expression of CEP164, which regulates DNA repair in response to UV damage (10);

- Changes to HOMER1, APP GP, and ARPP21 GP, indicating reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease and neurodegenerative disease (11);

- Changes to TMP3, TMP4, PLINK G4, CFL1, and PKM, indicating decreased risk of insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome (12).

There were no significant changes to traditional biomarkers such as weight or insulin resistance, which may be explained by the fact that subjects were healthy at baseline.

Overall, the researchers concluded intermittent fasting leads to changes in the proteome that are protective against cancer, inflammatory and immune disease, obesity, diabetes, the metabolic syndrome, and various pathological forms of cognitive dysfunction — even when applied to young, healthy humans. Proteomic studies such as this one are at best hypothesis-generating, but this study suggests fasting leads to significant shifts in protein expression that may reduce risk of disease, even in already healthy subjects who are not asked to change the composition of their overall diet. This suggests the use of fasting as a tool to improve metabolic health and lower disease risk, either independent of or alongside changes in overall diet, deserves further investigation.