A growing body of evidence suggests added sugars play a role in the development and/or progression of fatty liver disease. This 2018 trial, led by Miriam Vos (Emory) and Jeffrey Schwimmer (UCSD), considered whether removing sugar from the diet could improve fatty liver disease in children.

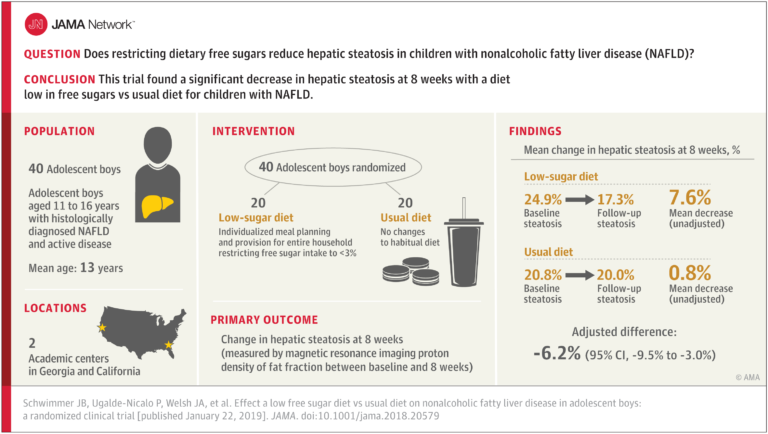

Forty adolescent boys were randomized to one of two diets for 8 weeks. Members of the control group continued to eat their usual diet. The treatment group was instructed to eat less than 3% of total calories from free (added) sugars. Investigators provided substantial support to help the subjects achieve this goal. First, study staff went to each participant’s household and replaced all sugar-containing foods with low-sugar or sugar-free substitutes (no artificial sweeteners were allowed). Each week, the family would then receive two shipments containing a complete diet, produced in a metabolic kitchen. They were instructed to eat no foods except those provided by the study staff. Eighteen out of 20 subjects successfully reduced free sugar intake to <3% of their total calories; by comparison, the control group consumed, on average, 10% of its calories from added sugars, which is in line with population averages.

The authors note:

Reduction of free sugars involves decreasing a number of dietary sugars including glucose, fructose, and sucrose commonly consumed in sweetened foods and beverages and in naturally sweet fruit juices. Biologically, fructose and fructose-containing sugars such as sucrose and high-fructose corn syrup appear to be of greater importance in elevating risk of liver fat accumulation than glucose, but both are sources of excess calories. Fructose increases hepatic de novo lipogenesis in a dose-dependent fashion and de novo lipogenesis has been shown to be abnormally unregulated in patients with NAFLD.

There was no difference in total calorie intake between groups, though the treatment group lost 2.0 kg on average. The treatment group also saw a mean reduction in liver fat from 25% to 17% (-6.23%), as well as significant improvements in secondary markers of liver health. Individual-level data shows changes in markers of liver health were small and inconsistent in members of the control group, but the majority of subjects in the treatment group saw improvements.

The authors conclude, “In this study of adolescent boys with NAFLD, 8 weeks of provision of a diet low in free sugar content compared with usual diet resulted in significant improvement in hepatic steatosis.” In other words, the trial showed that simply restricting sugar for 8 weeks in adolescent boys reduces liver fat content.

This trial must be seen as preliminary. Most of the subjects were Hispanic boys, and these results may not replicate in other populations. Additionally, the trial was too short to determine whether the benefits will continue to accumulate or plateau with continued sugar restriction—while the treatment led to improvements, all subjects still met the criteria for NAFLD when the trial was over. Finally, the highly-intensive intervention used here is unlikely to scale to larger clinical trials, let alone general practice.

These results should, however, be viewed in light of the fact that there is no existing pharmaceutical treatment for NAFLD. The current prescription for children with NAFLD—exercise, calorie restriction, and weight loss—is inconsistently effective for various reasons including compliance challenges. It is easier for adolescents to remove sugar from their diet than it is to sustainably reduce all calories, however. If larger trials were to replicate these results in the future, it would suggest sugar restriction could be a safe, effective tool to reverse NAFLD in adolescents.