Rotational Mechanics

After bounding, the next essential piece of the double-under is what Newman calls “rotational mechanics,” a term that refers to the positioning of the arms and hands. Poor hand positioning is one of the biggest causes of missed double-unders. As people get tired, their hands drift out from their body, which changes the shape of the rope.

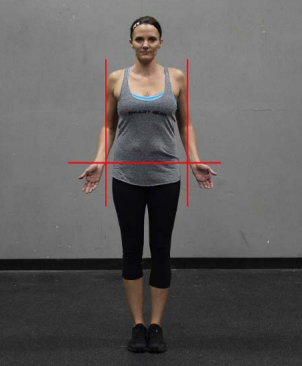

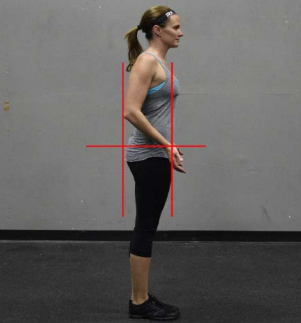

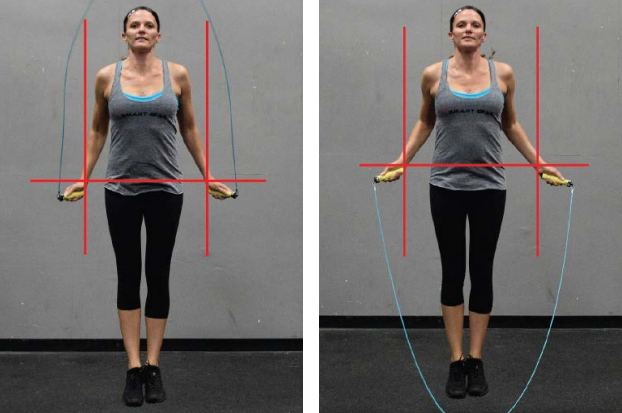

Ideally, the elbows should be by the athlete’s side and drawn back, with the palms forward. There should be about 4 to 6 inches between the hip crease and the wrist. If you were wearing a belt buckle—which is usually in the middle between the hip crease and hip bone—your wrists would be in line with the belt buckle.

“Without looking down, just using your peripheral vision, you should just see your hands wiggling,” Newman said.

“When you lose (sight of ) one or both hands, then your hands are out of position. When your hands are out of position, the spacing between you and the rope has just changed,” he said.

If your hands are too tight against your body, it creates a narrow rope shape. If the hands go too wide, the rope shortens. The ideal is a happy medium.

By using only the wrists to trace the PVC around the insides of the buckets, athletes can learn the correct rotational mechanics for double-unders.

The athlete should look at a spot on the ground about 10 to 15 feet in the distance. The goal is to have the rope hit the same spot each time, about 12 inches in front of your toes.

If your hands are too far forward, the rope is going to hit the ground farther out from the body, which causes the rope to rebound too quickly, Newman said.

“Those people are usually tuck jumpers—they have to get their feet out of the way,” Newman said.

“When their hands are too far out in front of them, they see the rope out in front of them and the rope keeps catching their feet, so they start raising their feet up to miss it. It’s counterintuitive for them to do the right thing, which is to pull the rope in closer to them so that the bottom-out point on the ground is closer to their feet,” he said.

Newman said he also sees people who “operate from the back seat.” These people jump with their hands too far back. In this case, the athlete uses more back and shoulder muscles, which is tiring, and the bottom-out point is too close to their toes.

The next element of rotational mechanics is wrist rotation.

“We want the wrist to do the swiveling,” Newman said. That means the wrist is disengaged from the arm. When the wrist is the swivel, the forearms and the grip can be relaxed.

“I can’t clench my fingers and have a really loose wrist,” Newman said. “If you lock down your wrist, that will promote a shoulder turn, which is not good.”

Newman said the movement is a snapping motion, like the one you’d do if you washed your hands and couldn’t find a towel. The snapping motion you’d use to dry your hands is the same type of movement you want in a double-under. The only difference is you are turning that snapping motion into a rotation. When it comes to rotational mechanics, the type of rope does make a difference.

Newman thinks a heavier rope helps the athlete feel the rhythm of the double-under.

“I don’t think beginners should use speed ropes,” Newman said. “They need to slow things down.”

Once the rope slows down, the athlete can make sure he is bounding off the toes and maintaining the correct hand positioning—from the first to the 50th double-under.

Comments on Double, Double Toil and Trouble

1 Comments

This is great! 🙌🏼🙌🏼 Thanks so much for posting! We do regular jumprope practice and this gives me some new things to try with our athletes!