In recent years, research on CrossFit has grown significantly, with numerous studies highlighting its effectiveness in improving a wide range of physical fitness characteristics (Schlegel 2020). This evidence supports what we see daily in affiliates: CrossFit delivers life-changing health and fitness outcomes for athletes.

A recently published article in the Journal of Physical Education and Sport aimed to review this growing body of research and provide insights into optimal training strategies. At first glance, it appears to provide a helpful summary of current scientific understanding. While the author, Dr. Ferdinando Cereda, acknowledges many of CrossFit’s physiological benefits, the article repeatedly emphasizes injury risk, often citing studies that are either irrelevant or misrepresented. In several instances, data appears unsupported, raising concerns about the article’s accuracy.

This pattern of errors echoes past challenges in CrossFit research, including those at issue in the CrossFit v. National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) litigation. In that case, a federal court ruled that the NSCA published false and fabricated data on CrossFit injury rates and awarded millions of dollars to CrossFit in sanctions for various discovery abuses, including perjury, evidence destruction, and concealment, highlighting the importance of scientific rigor. While there is currently no evidence linking Cereda’s study to similar intent, the inaccuracies in his article warrant scrutiny to ensure fair representation of CrossFit. Let’s take a closer look.

The article, “CrossFit®: A multidimensional analysis of physiological adaptations, psychological benefits, and strategic considerations for optimal training,” aims to summarize peer-reviewed findings on CrossFit to guide safer and more effective training methods. It offers some insights, such as improvements in cardiorespiratory function and community benefits, but its errors and omissions, particularly regarding injury risks, compromise its reliability.

Challenges in Studying CrossFit

Studying CrossFit with scientific reliability is inherently difficult due to its unique structure. The program’s constantly varied workouts, diverse participant demographics, and lack of standardized programming across affiliates make it challenging to design consistent studies. Small sample sizes, short study durations, and variable coaching strategies further complicate research, as noted in our broader analysis of exercise science. Cereda acknowledges these limitations but does not fully address their impact, leading to errors that skew the narrative. Highlighting these challenges can guide future research toward greater rigor and protect against the publication of misleading or poorly constructed studies.

Claim #1 – CrossFit Has Concerning Injury Rates

The word “injury” appears 38 times in the article, often framed like this: “Critics highlight concerns about injury rates, particularly among novices who may lack proper technique when performing complex lifts like snatches or muscle-ups. Studies report shoulder, knee, and lower back injuries as common, often linked to poor form or excessive volume (Hak et al., 2013; Weisenthal et al., 2014).”

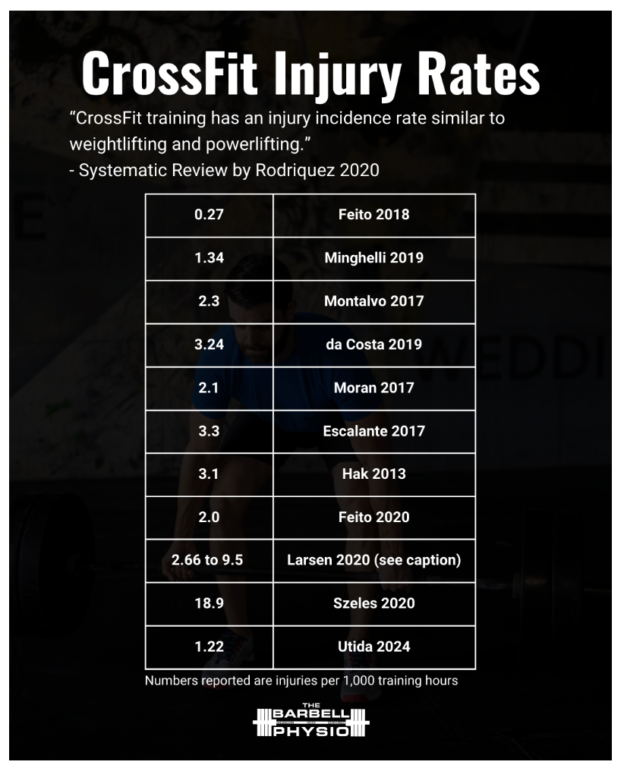

Given Cereda’s emphasis on injury risk, one would expect a thorough review of injury rate data. However, outside of this single reference, the article provides little discussion of such data. Notably, the cited study by Hak et al. (2013) supports CrossFit, finding an injury rate of 3.1 injuries per 1,000 training hours — a figure comparable to many recreational sports. This study, along with others, has led to two systematic reviews concluding that CrossFit’s injury risk is comparable to that of Olympic weightlifting, distance running, track and field, rugby, football, ice hockey, soccer, or gymnastics (Klimek 2018, Rodriguez 2022). Cereda’s article cites Hak et al. (2013) but omits this key finding, creating an unbalanced narrative. Responsible research requires presenting all relevant evidence, even when it challenges the author’s perspective.

The article notes: “The scientific literature exhibits significant methodological limitations—small sample sizes, inadequate controls, and insufficient longitudinal data—compromising the validity of both supportive and critical research positions.” While this is true, it does not justify omitting supportive data, such as Hak et al. (2013) and many others.

Claim #2 – CrossFit’s Advanced Methods Introduces Risk

Claim: “The democratization of high-intensity training has created unprecedented access to advanced training methodologies, yet simultaneously introduced risks for populations previously excluded from such protocols.”

Response: This argument, often raised by CrossFit critics, suggests Olympic lifts, box jumps, and rig-based skills are inherently risky. However, it overlooks CrossFit’s approach to scaling every workout to match an individual’s capacity, ensuring the same relative workout stimulus. Through CrossFit’s Level 1-Level 4 trainer curriculum and ongoing coach education, its coaches are taught how to modify any workout to accommodate any age, ability level, or limitation. CrossFit coaches customize workouts every day for every client who walks through the door. They deftly apply constantly varied, functional movements executed at high intensity through a lens of its charter — mechanics, consistency, and then intensity.

Later, Cereda acknowledges: “CrossFit®’s scalability allows athletes to tailor workouts to their fitness levels, fostering a sense of autonomy. For example, a beginner might substitute ring rows for pull-ups, while an advanced athlete adds weight to thrusters.” This contradiction highlights an inconsistent narrative, thereby undermining the clarity of the claim.

Claim #3 – Repetitive Overhead Lifts and Squatting Lead to Injuries

Claim: “Tibana and de Sousa (2018) identified rotator cuff strains and patellar tendinopathy as common issues, often linked to repetitive overhead lifts (e.g., snatches) and high-volume squatting.” It also states: “Muscle damage, quantified by creatine kinase (CK) levels, remains elevated for 48–96 hours after competitions (Tibana et al., 2018). CK levels >5,000 U/L indicate significant myofibrillar disruption, common in workouts emphasizing eccentric contractions (e.g., box jumps, kettlebell swings).”

Response: This claim is a shocking misrepresentation that casts a shadow over the article’s credibility. Tibana et al. (2018) examine lactate, heart rate, and perceived exertion in CrossFit workouts, with no mention of rotator cuff strains, patellar tendinopathy, CK levels, or myofibrillar disruption. To pin specific injuries and biomarkers on snatches and squats — core CrossFit movements — without evidence seems reckless, especially in a peer-reviewed journal. Such distortions could alarm athletes and coaches, eroding trust in CrossFit’s proven safety profile, as evidenced by Rodriguez (2020) and others. The complexity of studying CrossFit’s varied programming makes precision essential; however, this claim appears to fabricate data, undermining scientific integrity.

Claim #4 – CrossFit Leads to Burnout

Claim: “CrossFit®’s high-intensity model places participants at risk of Burnout and Overtraining Syndrome (OTS), characterized by prolonged fatigue, performance plateaus, and hormonal imbalances (e.g., suppressed testosterone, elevated cortisol). Drum et al. (2017) reported that 35% of CrossFitters experienced burnout within two years, with Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scores averaging 17/20 during peak training phases.”

Response: Drum et al. (2017) did not study burnout or report a 35% rate, nor did they mention RPE scores of 17/20. Ironically, Cereda elsewhere notes that CrossFit’s camaraderie “buffers against workout monotony and reduces dropout rates, which hover around 15% in CrossFit® compared to 50% in traditional gyms,” contradicting the burnout claim.

Claim #5 – The Movements Used in CrossFit Lead to Injuries

Claim: “CrossFit®’s emphasis on high-volume, high-intensity movements—particularly Olympic weightlifting and gymnastics—exposes participants to unique biomechanical risks. The snatch, clean-and-jerk, and overhead squats generate significant shear forces on vulnerable joints. For instance, during the snatch, the shoulder undergoes extreme external rotation and abduction under load, increasing the risk of rotator cuff impingement or labral tears (Rios et al., 2024). Similarly, the thruster… places compressive forces of up to 6× body weight on the knee joint… contributing to patellar tendinopathy (Tibana & de Sousa, 2018).”

Response: Rios et al. (2024) assessed cardiovascular responses to the CrossFit workout Isabel, with no discussion of shoulder biomechanics or rotator cuff risks. Tibana et al. (2018), which includes thrusters in Fran, does not mention knee joint loading or patellar tendinopathy. While biomechanical risks exist, these citations are inaccurate.

Claim #6 – Novices Get Hurt Too Often

Claim: “Novices are particularly vulnerable, as 60% of injuries occur within the first six months of training (Tibana et al., 2018). Poor technique—such as ‘loose elbows’ during cleans or inadequate hip engagement in snatches—amplifies joint stress.”

Response: This claim is a blatant fabrication that unfairly targets CrossFit’s accessibility. Tibana et al. (2018) do not discuss injury rates or novice athletes, rendering the 60% statistic a baseless invention. Such a claim could scare off new participants, a vital demographic for CrossFit’s inclusive, scalable model, which carefully tailors workouts to beginners. Larsen et al. (2020) show that novice injuries often stem from pre-existing conditions, not CrossFit itself, with new injury rates significantly lower. Given the challenge of standardizing CrossFit studies across diverse populations, this kind of error is not just sloppy — it’s a disservice to the fitness community, misrepresenting a program designed to empower all athletes.

Claim #7 – Ego Lifting Causes Injuries, and Workouts Are Too Heavy

Claim: “Ego lifting (using weights beyond one’s capacity) exacerbates risks; a 2023 study found that 40% of male CrossFitters admitted to lifting ≥90% of their 1RM during WODs, despite fatigue-induced form breakdown.”

Response: None of the 2023 studies in the article’s references support this 40% statistic. Lifting >90% of 1-rep max in met-cons is rarely feasible and typically not programmed, though heavy strength workouts may approach such loads, making the claim misleading.

Claim #8 – Constantly Varied Programming Leads to Injuries

Claim: “Non-periodized programming—common in casual CrossFit® boxes—is a key driver of overuse injuries. A 16-week periodized model, as proposed by Foster et al. (2017), balances stress and recovery… This approach lowers injury risk by 35% compared to non-structured programs.”

Response: Foster et al. (2017) review training load monitoring, with no mention of periodization or a 35% reduction in injuries. The claim that a periodized model reduces injury risk by 35% is fabricated.

It’s also possible that CrossFit’s varied programming may help reduce overuse injuries by diversifying movement patterns and regularly shifting load demands across different body regions, potentially preventing excessive stress on any one tissue. While this is a compelling hypothesis, it remains unstudied.

Claim #9 – Wearable Technology Reduces CrossFit Injuries

Claim: “The integration of advanced technology into CrossFit® programming represents a paradigm shift in how athletes train and recover. Wearable sensors, such as WHOOP straps and Polar chest monitors, already track real-time physiological metrics like heart rate variability (HRV), bar velocity, and ground reaction forces. For instance, Rios et al. (2024) demonstrated that monitoring barbell kinematics (e.g., peak velocity during cleans) with inertial measurement units (IMUs) can identify technical flaws, such as early arm pull, which increase injury risk by 18%.”

Response: Rios et al. (2024) do not discuss barbell kinematics or injury risk, making the 18% claim unsupported.

Claim #10 – Motion-Capture Devices Reduce CrossFit ACL Injuries

Claim: “A 2023 pilot study using EMG sensors and motion capture reduced anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries by 40% in a CrossFit® cohort by alerting athletes to risky mechanics in real time.”

Response: This claim is an egregious concoction, conjuring a phantom study to inflate CrossFit’s risks. No 2023 study in the bibliography mentions ACL injuries or EMG sensors, and a PubMed search for “CrossFit” and “ACL tear” yields no relevant studies, underscoring the rarity of ACL injuries in CrossFit. Inventing a 40% reduction implies a significant problem that doesn’t exist, which could potentially alarm affiliates and athletes. Pilot studies lack the power to detect rare injury reductions, rendering this claim not only unfounded but also scientifically implausible. The difficulty of studying CrossFit’s varied movements demands rigorous sourcing, yet this fabrication betrays that standard, casting doubt on the article’s entire narrative.

Claim #11 – We Should be Concerned About Lifelong CrossFit Participation and Heart Health

Claim: “Tibana et al. (2017) observed… elevated cardiac troponin levels post-competition hint at transient myocardial stress, raising concerns about lifelong practitioners.”

Response: This claim is a dangerous distortion that threatens CrossFit’s reputation with baseless fearmongering. Tibana et al. (2017) studied hypotensive effects, not cardiac troponin or myocardial stress. Inventing a heart health risk in a peer-reviewed journal is reckless, especially when cardiorespiratory fitness gains, like increased VO2 max, reduce cardiovascular risk and lower all-cause mortality (Kodama, 2009). Studying CrossFit’s high-intensity model requires precision, but this fabricated claim undermines trust, potentially scaring participants from a program proven to enhance health.

Claim #12 – Aging Populations Should Be Concerned About Joint Health

Claim: “Longitudinal studies are needed to assess… musculoskeletal impacts of CrossFit®, particularly in aging populations where high-intensity training may offer both benefits (e.g., bone density preservation) and risks (e.g., joint degeneration).”

Response: While the call for longitudinal studies is reasonable and scientifically appropriate, the author’s framing of potential “risks” in older adults — without a balanced discussion of well-documented benefits — creates an unbalanced narrative.

Aging populations face significant declines in strength, muscle mass, power, and functional capacity, all of which contribute to reduced independence and quality of life. CrossFit® has been shown to improve these areas of fitness (Schlegel 2020), while also providing community support and psychological benefits that are especially valuable in older populations who may face increased social isolation.

Moreover, existing research supports the idea that appropriately dosed and progressed resistance and high-intensity training can improve musculoskeletal health without inherently accelerating joint degeneration (Vincent et al., 2012; Turner, 2020). To suggest otherwise, particularly in the absence of evidence, skews the narrative and misrepresents the broader body of literature.

Claim #13 – Technique Workshops Reduce Injuries by 25%

Claim: “Schlegel (2020) demonstrated that structured technique workshops reduced injury rates by 25% in a cohort of 200 CrossFitters.”

Response: This claim is a stunning lapse in scholarship, exposed by Cereda’s own admission. Schlegel (2020) is a review article, not a study, as he reports. The review makes no mention of workshops or injury rates.

In an email (April 29, 2025), Cereda conceded this was a “misattribution or transcription mistake” and could not verify the source, confirming its falsehood. Such a specific, invented statistic misleads coaches and affiliates about injury prevention, eroding trust in CrossFit’s evidence-based practices. The challenge of studying CrossFit’s diverse programming demands meticulous citations, yet this error reveals a troubling disregard for accuracy in a peer-reviewed work.

Conclusion

This article could have been a valuable overview of CrossFit’s transformative benefits, from strength and cardiorespiratory gains to community-driven motivation. But its litany of errors — unsupported claims, grossly misrepresented studies, and critical omissions — shatters its credibility. The five most egregious inaccuracies, including fabricated cardiac risks, phantom ACL studies, and invented novice injury rates, not only mislead readers but also threaten CrossFit’s reputation as a safe, effective fitness program.

These errors do not appear to be mere oversights; they seem to reflect a troubling disregard for scientific rigor, especially given the challenges of studying CrossFit’s varied programming, diverse participants, and lack of standardization. As seen in the NSCA case, where false data harmed CrossFit, such scientific inaccuracies can have real consequences. Cereda and the Journal of Physical Education and Sport may want to consider issuing a prompt correction to restore accuracy and ensure CrossFit is fairly represented. Peer-reviewed science must also rise above distortion to support the fitness community, and rigorous, transparent research is essential to honor the millions who rely on CrossFit for health and vitality.

References

Drum SN, Bellovary BN, Jensen RL, Moore MT, Donath L. Perceived demands and postexercise physical dysfunction in CrossFit® compared to an ACSM based training session. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2017 May;57(5):604-609. doi: 10.23736/S0022-4707.16.06243-5. Epub 2016 Feb 12. PMID: 26954573.

Ferndinando C. CrossFit®: A multidimensional analysis of physiological adaptations, psychological benefits, and strategic considerations for optimal training. Journal of Physical Education and Sport. 2025; 25(3): 601-610. https://efsupit.ro/images/stories/march2025/Art%2065.pdf

Foster C, Rodriguez-Marroyo JA, de Koning JJ. Monitoring Training Loads: The Past, the Present, and the Future. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2017 Apr;12(Suppl 2):S22-S28. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2016-0388. Epub 2017 Mar 2. PMID: 28253038.

Hak PT, Hodzovic E, Hickey B. The nature and prevalence of injury during CrossFit training. J Strength Cond Res. 2013 Nov 22. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000318. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 24276294.

Klimek C, Ashbeck C, Brook AJ, Durall C. Are Injuries More Common With CrossFit Training Than Other Forms of Exercise? J Sport Rehabil. 2018 May 1;27(3):295-299. doi: 10.1123/jsr.2016-0040.

Kodama S, Saito K, Tanaka S, Maki M, Yachi Y, Asumi M, Sugawara A, Totsuka K, Shimano H, Ohashi Y, Yamada N, Sone H. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in healthy men and women: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009 May 20;301(19):2024-35. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.681. PMID: 19454641.

Larsen RT, Hessner AL, Ishøi L, Langberg H, Christensen J. Injuries in Novice Participants during an Eight-Week Start up CrossFit Program-A Prospective Cohort Study. Sports (Basel). 2020 Feb 13;8(2):21. doi: 10.3390/sports8020021. PMID: 32069804; PMCID: PMC7077206.

Rios M, Becker KM, Cardoso F, Pyne DB, Reis VM, Moreira-Gonçalves D, Fernandes RJ. Assessment of Cardiorespiratory and Metabolic Contributions in an Extreme Intensity CrossFit® Benchmark Workout. Sensors (Basel). 2024 Jan 14;24(2):513. doi: 10.3390/s24020513. PMID: 38257605; PMCID: PMC10819656.

Rodríguez M, García-Calleja P, Terrados N, Crespo I, Del Valle M, Olmedillas H. Injury in CrossFit®: A Systematic Review of Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Phys Sportsmed. 2022 Feb;50(1):3-10. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2020.1864675. Epub 2021 Jan 7. PMID: 33322981.

Schlegel P. CrossFit® Training Strategies from the Perspective of Concurrent Training: A Systematic Review. J Sports Sci Med. 2020 Nov 19;19(4):670-680. PMID: 33239940; PMCID: PMC7675627.

Tibana RA, Almeida LM, DE Sousa Neto IV, DE Sousa NMF, DE Almeida JA, DE Salles BF, Bentes CM, Prestes J, Collier SR, Voltarelli FA. Extreme Conditioning Program Induced Acute Hypotensive Effects are Independent of the Exercise Session Intensity. Int J Exerc Sci. 2017 Dec 1;10(8):1165-1173. doi: 10.70252/CDFU3385. PMID: 29399246; PMCID: PMC5786200.

Tibana RA, De Sousa NMF, Prestes J, Voltarelli FA. Lactate, Heart Rate and Rating of Perceived Exertion Responses to Shorter and Longer Duration CrossFit® Training Sessions. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2018 Nov 28;3(4):60. doi: 10.3390/jfmk3040060. PMID: 33466988; PMCID: PMC7739245.

Turner MN, Hernandez DO, Cade W, Emerson CP, Reynolds JM, Best TM. The Role of Resistance Training Dosing on Pain and Physical Function in Individuals With Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review. Sports Health. 2020 Mar/Apr;12(2):200-206. doi: 10.1177/1941738119887183. Epub 2019 Dec 18. PMID: 31850826; PMCID: PMC7040944.

Vincent KR, Vincent HK. Resistance exercise for knee osteoarthritis. PM R. 2012 May;4(5 Suppl):S45-52. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.01.019. PMID: 22632702; PMCID: PMC3635671.

About the Author

Zach Long is a Doctor of Physical Therapy at Onward Physical Therapy, the founder of TheBarbellPhysio.com, and co-founder of PerformancePlusProgramming.com. He specializes in mobility, strength, and prehab programming for fitness athletes. He is passionate about helping athletes optimize performance and prevent injury through evidence-based strategies and expert coaching.

Zach Long is a Doctor of Physical Therapy at Onward Physical Therapy, the founder of TheBarbellPhysio.com, and co-founder of PerformancePlusProgramming.com. He specializes in mobility, strength, and prehab programming for fitness athletes. He is passionate about helping athletes optimize performance and prevent injury through evidence-based strategies and expert coaching.