The muscles of the ankle, like its skeletal architecture, are essential to function. There are a number of muscles that dorsiflex, plantar flex, evert, and invert the foot at the ankle. Together, these muscles can also act to stabilize the joints they cross during locomotion.

The muscles acting at the ankle and foot can attach as high on the leg as the femoral condyles and as low as the distal tibia and fibula. The muscles attach distally at multiple locations, from the most posterior calcaneus to as far forward as the phalanges (toes). Note, as discussed previously, that muscles crossing more than one joint will have more than one function.

The posterior muscles of the lower leg (the calf) are the largest and most powerful of the three groups of muscles present (posterior, anterior, and lateral). Their primary function is plantar flexion, with each muscle having additional movement roles. These muscles are heavily oxidative, with 50% or more of their fibers being of the distinctly slow oxidative variety and a majority of the remaining half being fast oxidative-glycolytic fibers. This fiber profile is indicative of the muscles’ strong postural function, but their mass relative to the other two extrinsic groups indicates they have an equally strong ambulatory function.

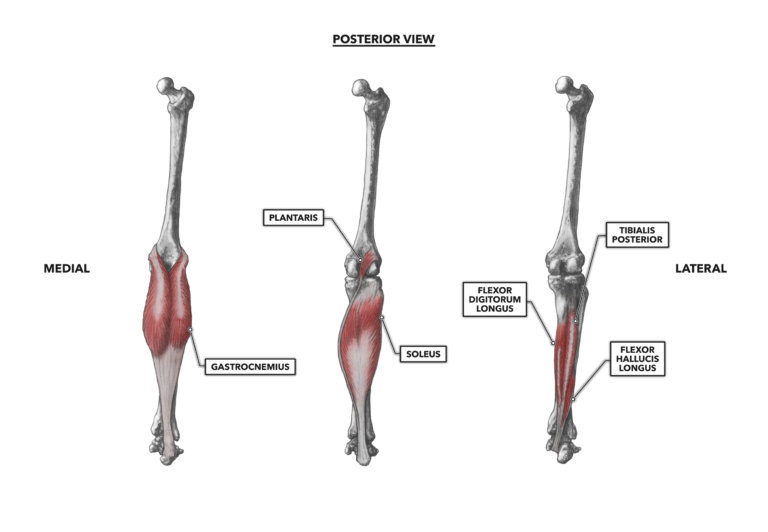

Figure 1: Posterior musculature of the ankle

Gastrocnemius – The gastrocnemius, frequently referred to as a “gastroc,” is the largest muscle of the posterior group. It is a pennate muscle with two distinct heads and a distal tendon of attachment that it shares with several underlying muscles. Its proximal attachments occur with each muscular head, medial and lateral, attaching at the posterior surface of the medial and lateral femoral epicondyles, just superior to the condyles. Both heads fuse into a single distal tendon that attaches to the posterior and superior surface of the calcaneus. This distal tendon is commonly called the Achilles tendon but can also be called the calcaneal tendon.

The accepted distal function of the gastrocnemius is plantar flexion at the ankle with the foot pushing a resistance down (as in using a shovel) or pushing the body up (as in a calf raise). This movement occurs with every stride of locomotion we take and is part of many exercise and sport movements. However, if the foot is held immobile and flat on the floor, then the distal function is strictly postural: The muscle pulls the mass of the body to the rear, cooperatively balancing the actions of the anterior musculature to maintain the center of gravity over the base provided by the feet.

The gastrocnemius crosses two joints, and as such, it has both a proximal and a distal function. One proximal function is flexion of the knee; if the foot is the least stable end of the system, the proximal action will be lower leg movement, rearwards in an arc around the knee. If the foot is immobile, the proximal function will be to assist in “locking out” the knee, pulling the distal femur into vertical alignment with the proximal tibia.

Soleus – The soleus lies beneath the gastrocnemius and is a fairly thin muscle. In lean individuals it can be seen protruding slightly, just inferior and anterior to the major bellies of the gastrocnemius. The soleus attaches proximally to both the tibia and the fibula. Distally, the tendon of the soleus fuses with that of the gastrocnemius to form the calcaneal tendon.

The soleus crosses one joint: the ankle. By virtue of its central orientation, if the foot is not planted, the soleus will produce plantar flexion. If the foot is held fixed to the floor, the soleus will act as a postural muscle and pull the mass of the body posteriorly. This latter role is the primary function of the soleus, as it contributes greatly to maintaining balance while standing. Because 60% or more of its fibers are slow oxidative fibers, it is well adapted to this function.

Plantaris – The proximal and distal attachment sites of the plantaris occur along the lateral supracondylar ridge of the femur and the calcaneus, respectively. The muscle is generally not more than about four inches (10 cm) in length. It has a long, thin tendon that courses down to the calcaneus (heel). The proximal and primary function of the plantaris is knee flexion, but its tendon also merges with the calcaneal tendon of the gastrocnemius. It thus has a distal function as a weak plantar flexor.

Flexor digitorum longus – The flexor digitorum longus muscle is, as the name implies, a long one. It is a flexor of the digits, meaning it passes behind the medial malleolus and attaches inferiorly to the phalanges. The muscle attaches proximally on the middle-third of the medial aspect of the tibia. Its central tendon passes behind the medial malleolus. It then angles laterally across the bottom of the feet to split into four slips of tendon attaching to the base of each distal phalanx of phalanges two through five. Although it is named according to its function to flex the toes, the primary function of the flexor digitorum longus is to plantar flex the ankle during locomotion. As with other members of the posterior group, it is also active in postural control when the foot is the most stable structure.

Tibialis posterior – The nomenclature yields the clues needed to localize this muscle to the posterior surface of the tibia, but there is more to the tibialis posterior. The proximal attachment of the muscle is divided between the lateral aspect of the shaft of the tibia, the medial aspect of the fibula, and the interosseous membrane (connective tissue spanning the space between the tibia and fibula) from the level just inferior to the head of the fibula to approximately halfway down the length of the fibula. After the tendon passes behind the medial malleolus, the distal attachment is quite complex, with connections on the plantar surface of seven bones: the navicular, all three cuneiforms, and the second, third, and fourth metatarsals. Aside from the plantar flexion and inversion functions, the tibialis posterior is involved in both anterio-posterior and medio-lateral postural control.

Flexor hallucis longus – As you might expect, the flexor hallucis longus flexes the hallux (the big toe). “Flexor” indicates it is a posterior muscle. The muscle attaches proximally on the posterior of roughly the middle-third of the fibula and then crosses the tibia and passes behind the medial malleolus. It attaches distally under the base of the distal phalanx of the hallux. As it passes behind the medial malleolus, it contributes to plantar flexion in addition to its primary function of flexing the hallux.

To learn more about human movement and the CrossFit methodology, visit CrossFit Training.