This highly influential 2008 trial considered the impact of rosuvastatin, commonly known as Crestor, on heart disease risk.

The JUPITER trial differed from most other statin trials in two key areas. First, it was a primary prevention trial. Prior to JUPITER, statins were indicated only for hyperlipidemics and some others at high risk of heart disease. JUPITER deliberately chose a group of subjects who had, by traditional metrics, much lower risk of heart disease: men with LDL cholesterol below 130 mg/dL. The motivation was to determine if Crestor could be indicated for men who were not at high risk of a cardiovascular event. The second way in which JUPITER differed from other statin trials was that it sought to establish a new risk marker in the place of LDL—i.e., C-reactive protein—as the basis for prescribing the drug.

The trial design was relatively simple: 17,802 men and women between the ages of 50 and 60 with an LDL-C less than 130 mg/dL and high C-reactive protein (> 2.0 mg/L) were randomized to receive 20 mg of rosuvastatin (Crestor). Recruiting these subjects was a massive endeavor, drawing from 1,315 sites across 26 countries. Subjects were expected to be followed for five years. The primary outcome was an unusual compound measure: “first major cardiovascular event, defined as nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, an arterial revascularization procedure, or confirmed death from cardiovascular causes.” The trial was scheduled to end once 520 of these cardiovascular events were observed, based on a preliminary power analysis. Randomization was excellent with few differences between treatment and placebo groups at baseline.

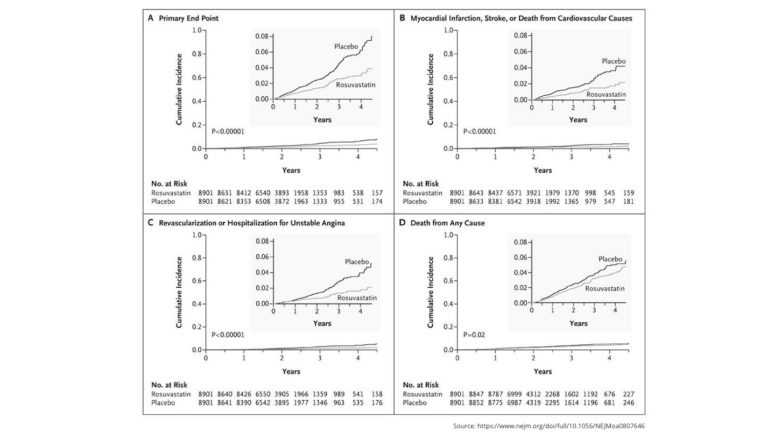

The trial was terminated early at a median follow-up of 1.9 years after 142 “first major cardiovascular events” had been observed in the treatment group and 251 in the control (393 total). The rates of primary endpoint per 100 person-years were 0.77 and 1.36, respectively, providing an HR of 0.56 for the treatment group with regard to the primary endpoint. Within the (approximately) two-year duration of the study, the number that needed to be treated to prevent one major cardiovascular event (NNT) was 95. All results were statistically significant.

The treatment group showed similar improvements in individual cardiovascular event measures including heart attacks (HR = 0.46) and strokes (0.52) (both significant). Additionally, there were 1.00 and 1.25 deaths per 100 person-years in the treatment and placebo groups, respectively, providing a significant HR = 0.80 for all-cause mortality for rosuvastatin. A subgroup analysis showed rosuvastatin led to statistically significant improvements in the primary endpoint in all groups, such as those divided according to sex, age, race, and other characteristics.

Cumulative Incidence of Cardiovascular Events According to Study Group. Figure 1 from Rosuvastatin to Prevent Vascular Events in Men and Women with Elevated C-Reactive Protein.

The rosuvastatin group showed a dramatic decrease in LDL cholesterol (to 55 mg/dL, compared to 110 mg/dL in placebo) and C-reactive protein (2.2 mg/L vs. 3.5 mg/L in placebo). The one significant adverse effect was a 25-percent increase in newly diagnosed diabetes in the treatment group (270 cases vs. 216 in controls).

Despite these impressive results, some elements of the trial were unusual, if not questionable. The first and most visible issue was the decision to stop the trial early based on the relative effectiveness of rosuvastatin. While this decision was made by an independent review board, this board also showed some conflicts of interest. This is particularly concerning in light of previous research suggesting trials that are stopped early tend to show artificially high effect sizes(1). Equally important, the short observation period limits our ability to understand the long-term impact of rosuvastatin. This is critical, given that JUPITER was a primary prevention trial in low-risk individuals and thus designed specifically to justify providing the drug to large populations for long periods even when the risk of an immediate cardiovascular event is low.

Additionally, there were major conflicts of interest. As expected, the trial was entirely funded by AstraZeneca, and many of the individual authors had pharma-related conflicts of interest. Additionally, the PI, Paul Ridker, was a co-inventor of a patent related to testing C-reactive protein.

Collectively, these and other errors have called into question the results of the JUPITER trial.