Adapted from Coach Glassman’s Dec. 1, 2007, L1 lecture in Charlotte, North Carolina, and originally published in the CrossFit Level 1 Training Guide.

In no small part, what is behind this program is the quantification of fitness. This means we put a number on fitness: work capacity across broad time and modal domains. You can assess one’s fitness by determining the area under his or her work-capacity curve. This would be similar to a group of athletes competing in 25 to 30 workouts. Include a range of activities—like three pulls on the Concept2 rower for average watts to a 10-mile run—and a multitude of workouts in between. Compile their overall placing across these events, and everyone then has a reasonable metric of his or her total capacity.

This quantification of fitness is a part of a broader concept that is at the heart of this movement: We call it evidence-based fitness. This means measurable, observable, repeatable data is used in analyzing and assessing a fitness program. There are three meaningful components to analysis of a fitness program: safety, efficacy, and efficiency.

The efficacy of a program means, “What is the return?” Maybe a fitness program advertises that it will make you a better soccer player. There needs to be evidence of this supported by measurable, observable, repeatable data. For CrossFit, we want to increase your work capacity across broad time and modal domains. This is the efficacy of this program. What are the tangible results? What is the adaptation that the program induces?

Efficiency is the time rate of that adaptation. Maybe the fitness program advertises that it can deliver 50 pull-ups. There is a big difference whether it takes six months versus nine years to achieve that.

Safety is how many people end up at the finish line. Suppose I have a fitness program. I start with 10 individuals: Two of them become the fittest human beings on Earth and the other eight die. While I would rather be one of the two fittest than the eight dead, and I do not know if I want to play, I am not going to attach a normative value to it. The real tragedy comes in not knowing the safety numbers.

These three vectors of safety, efficacy and efficiency point in the same direction, such that they are not entirely at odds with each other. I can greatly increase the safety of a program by turning the efficacy and efficiency down to zero. I can increase the efficiency by turning up the intensity and then possibly compromising safety. Or I could damage the efficacy by losing people. Safety, efficacy and efficiency are the three meaningful aspects of a program. They give me all I need to assess it.

This quantification of fitness, by choosing work capacity as our standard for the efficacy of the program, necessitates the qualification of movement. Our quantification of fitness introduces qualification of movement.

For the qualification of movement there are four common terms: mechanics, technique, form and style. I will not delve into them with too much detail: The distinction is not that important. I use both technique and form somewhat interchangeably, although there is a slightly nuanced distinction.

When I talk about angular velocity, momentum, leverage, origin or insertion of muscles, torque, force, power, relative angles, we are taking about mechanics. When I speak to the physics of movement, and especially the statics and less so the dynamics, I am looking at the mechanics.

Technique is the method to success for completion of a movement. For example, if you want to do a full twisting dismount on the rings, the technique would be: pull, let go, look, arm up, turn, shoulder drop, etc. Technique includes head posture and body posture. And there are effective and less effective techniques. Technique includes the mechanics, but it is in the macro sense of “how do you complete the movement without the physics?”

Form is the normative value: This is good or this is bad—“you should” or “you shouldn’t” applied to mechanics and technique.

Style is essentially the signature to a movement; that is, that aspect of the movement that is fairly unique to you. The best of the weightlifting coaches can look at the bar path during a lift and tell you which lifter it is. There are aspects to all of our movements that define us like your thumbprint. It is the signature. To be truly just the signature, style elements have no bearing on form, technique or mechanics. Style does not enter into the normative assessment, is not important to technique, and does not alter substantially the physics.

These four terms are all qualifications to movement. I want to speak generally to technique and form to include all of this, but what we are talking about here is the non-quantification of output; that is, how you move.

By taking power or work capacity as our primary value for assessing technique—and this reliance on functional movement—we end up in kind of an interesting position. We end up where power is the successful completion of functional movement.

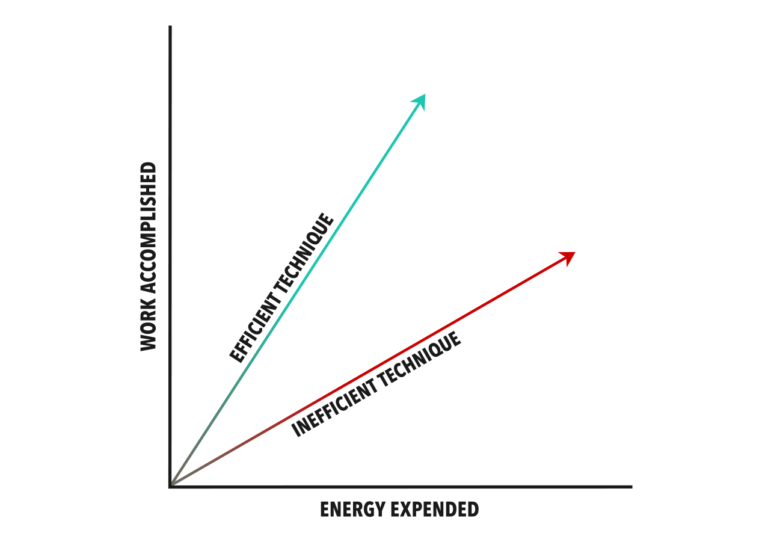

This is not about merely energy exerted. On a graph, you could put work accomplished on the Y-axis and energy expended on the X-axis. Someone could potentially expend a lot of energy and do very little work by being inefficient. Ideally, what that individual would do would see little energy expended for the maximum amount of work. Technique is what maximizes the work completed for the energy expended (Figure 1). For any given capacity, say metabolically, for energy expenditure, the guy who knows the technique is going to be able to do the most amount of work.

Suppose I take two people at random and they are both trying the same task. One is familiar with how to deadlift, and one is not. One knows how to clean, one does not. One knows how to drive overhead, one does not. Suppose they are loading a truck with sandbags. The one familiar with lifting large objects and transporting them is going to do a lot more work.

You can have the argument as to who is stronger. For example, you can use an electromyogram and see with what force the biceps shortens. If you are defining strength as contractile potential, you may end up with the guy with enormous contractile potential—but not knowing the technique of the clean, the jerk, the deadlift, he cannot do as much work.

We, however, do not take contractile potential as the gold standard for strength. Strength is the productive application of force. If you cannot complete work, if you cannot express strength as power, if strength cannot be expressed as productive result, it does not count. Having enormous biceps and quadriceps is useless if you cannot run, jump, lift, throw, press.

This is related to safety, efficacy and efficiency because technique (quality of movement) is the heart of maximizing each of these.

He or she who knows how to do these movements when confronted with them will get a better result in terms of safety. Two individuals attempt to lift a heavy object; one knows how to pop a hip and get under it (clean), and the other guy starts to pull with a rounded back. I can tell you what is likely to happen to he or she who does not know how to lift. If you want to stay safe, you better have good technique, good form.

Efficacy, for any given contractile potential, for any given limit to your total metabolic capacity, he or she who knows the technique will be able to get more work done and will develop faster. If after six months of teaching you how to clean it still does not look like I would like it to, you will not get twice body weight overhead more quickly someone who looks like a natural. You want an effective program, you are going to have to move with quality, you want to get the result quickly—technique is going to be pivotal to your success.

Technique is an intimate part of safety, efficacy, and efficiency.

We can see how this manifests in CrossFit workouts by way of a comparison. I want to look at typing, shooting, playing the violin, NASCAR driving and CrossFit. What these domains have in common is that a marked proficiency is associated with speed. Being able to shoot accurately and quickly is better than quickly or accurately.

You may try to get a job as a typist because you do not make any mistakes. However, for this perfection, you type at a rate of 20 words a minute and only use two fingers. You will never get hired. Playing the violin fast and error-free is critical for a virtuoso. However, someone who gets through “Flight of the Bumblebee” in 12 minutes is not there yet. A NASCAR driver wants to both drive fast and not wreck. In CrossFit, a perfectly exquisite Fran is worthless if it takes 32 minutes.

And yet, it is presented to CrossFit coaches as, “Should I use good form or should I do it quickly?” I do not like my choices. One is impossible without the other.

Technique and speed are not at odds with one another, where “speed” is related to all the quantification of the movement: power, force, distance, time. They are seemingly at odds. It is a misapprehension. It is an illusion.

Can you learn to drive fast without wrecking? Can you learn to type fast without making errors? Can you shoot quickly without missing? Eventually, but not in the learning. One is impossible without the other.

You will not learn to type fast without typing where you make a ton of errors and then work to reduce the errors at that speed. Then you go faster, and then again pull the errors back in, then go faster and pull the errors back in. You drive faster and faster and then you spin out in the infield or you hit the wall.

If you are a race driver and you have never spun out, gone out in the infield or never been in a wreck, you are not very good. If you are a typist and you have never made a mistake, you are very slow. In CrossFit, if your technique is perfect, your intensity is always low.

Here is the part that is hard to understand: You will not maximize the intensity or the speed without mistakes. But it is not the mistakes that make you faster. It is not reaching for the letter P with your pinky and hitting the O. It is not hitting the wrong note that made you play faster. It is not missing the target by two feet that made you a better shooter. It is not running into the wall that made you a faster driver. But you will not get there without it. The errors are an unavoidable consequence of development.

This iterative process of letting this scope of errors broaden then reducing them without reducing the speed is called “threshold training.”

In a CrossFit workout, if you are moving well, I will tell you to pick up the speed. Suppose at the higher speed the movement still looks good: I will encourage you to go faster. And if it still looks good I will encourage you to go even faster. Now the movement starts falling apart.

I do not want you to slow down yet. First, at that speed I want you to fix your technique. What you need to do is continuously and constantly advance the margins at which form falters.

It may be that initially at 10,000 foot-pounds per minute my technique is perfect, but it falls apart at 12,000 foot-pounds per minute. Work at that 10,000 to 12,000 foot-pounds per minute mark to fix the form, and soon enough you will have great technique at 12,000 foot-pounds per minute. The next step is to achieve that technique at 14,000 foot-pounds per minute.

At first, the technique at 14,000 foot-pounds per minute will suffer. Then you must narrow it in. That is the process. It is ineluctable. It is unavoidable. There is nothing I can do about it. That is not my rule.

We are the technique people. We drill technique incessantly, but simultaneously I want you to go faster. You will learn to work at higher intensity with good technique only by ratcheting up the intensity to a point where good technique is impossible. This dichotomy means that it is impossible at the limits of your capacity to obey every little detail and nuance of technique. Some of the refined motor-recruitment patterns are not going to always look perfect.

I do not know of a domain where speed matters and technique is not at the heart of it. In every athletic endeavor where we can quantify the output, there is incredible technique at the highest levels of performance.

Suppose someone set the new world record for the shot put, but his technique was poor. This means one of two things: one, either with good technique it would have gone farther, or two, we were wrong in understanding what is good technique.

Technique is everything. It is at the heart of our quantification. You will not express power in significant measure without technique. You might expend a lot of energy, but you will not see the productive application of force. You will not be able to complete functional tasks efficiently or effectively. You will not be safe in trying.

There is a perceived paradox here that really is not a paradox when you understand the factors at play.

Related Content:

- Watch Technique, Part 1

- Watch Technique, Part 2: Q & A

To learn more about human movement and the CrossFit methodology, visit CrossFit Training.