This 2016 commentary argues increased rates of obesity in the United States and other Western nations are not due to a decrease in physical activity.

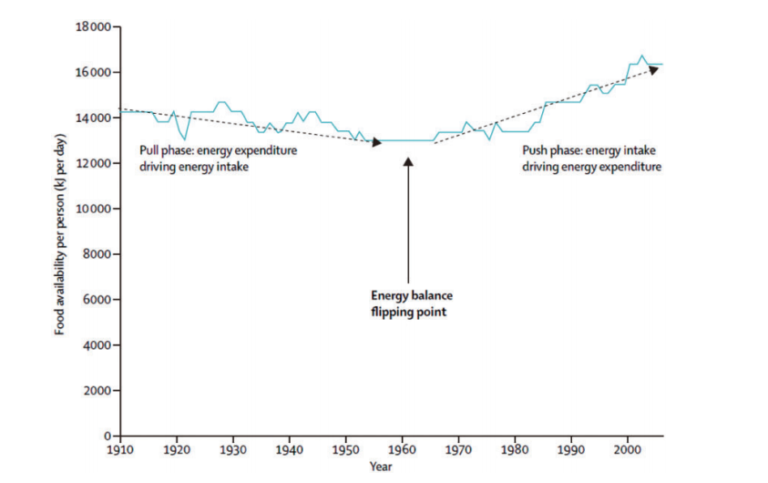

First, observational data does not indicate there are any meaningful differences in physical activity levels between populations with varying rates of obesity. Public health authorities have argued that mechanization, motorization, and other factors have led modern Western populations to move less than previous generations (1). The development of the obesity epidemic, however, fails to parallel this shift. Obesity rates began to rise in the mid-1960s, long after technology and culture supported these modern conveniences (2) (Figure 1). Similarly, studies using doubly labeled water, the most rigorous tool used to measure energy expenditure in free-living populations, have shown no difference in mean activity levels between modern agrarian/hunter-gatherer populations and Westerners of similar age and weight. Similarly, there is no relationship between economic development and (decreased) physical activity (3).

Figure 1: Prior to the 1960s, decreases in energy expenditure (due to various social and technological factors) likely drove a small decrease in energy intake. Since the 1960s, however, energy intake has increased without a compensatory increase in energy expenditure.

Second, it is biologically implausible for a decrease in physical activity to lead to weight gain or an increase in physical activity to prevent it. Our appetite and inclination to move are both tightly regulated across a variety of organ systems. These systems are sufficiently sophisticated to keep a healthy adult, prior to current Western societies, at a stable weight throughout adulthood without requiring any deliberate attention to be paid to either energy intake or expenditure. Clinical trials have demonstrated that an increase in physical activity is generally met with an increase in food intake, and vice versa, with this compensatory response visible over a period of weeks rather than days (4). In fact, the effectiveness of these regulatory systems indicates foods that resist these appetite-regulating mechanisms, such as added sugars and especially beverage sugars, may uniquely promote obesity.

Epidemiological evidence within Western populations is difficult to interpret, given well-known fatal flaws in the tools used to assess both dietary intake and energy expenditure, particularly with regard to obese individuals (6). To the extent this data can be interpreted, however, it does not suggest decreased physical intake increases future weight, nor that increased physical activity prevents weight gain. The estimated amount of calories burned by the average American due to deliberate energy expenditure is likely trivial, with men averaging 35 minutes and women averaging 21 minutes per day in “moderate or vigorous” physical activity, a category that can include walking, gardening, and golf (7).

The authors strongly emphasize these claims in no way undermine the established relationships between exercise and disease prevention, and similarly encourage Americans to exercise as much as they are willing and able (8). Specifically, the authors conclude the data clearly indicates the cause of the current obesity epidemic was not a decrease in physical activity within the U.S. population. Instead, they argue, the cause lies in changes to our diet.