Question

How might impairments in glucose metabolism lead to the development and/or progression of Alzheimer’s disease?

Takeaway

Multiple lines of research suggest defective glucose and/or insulin activity contribute to, and may cause, Alzheimer’s pathology. This same metabolic hypothesis also could explain the significance of known genetic risk factors for Alzheimer’s. Future research will explore whether this metabolic hypothesis translates into effective therapies to prevent and/or treat cognitive impairment.

This 2020 review surveys the literature on the increasingly popular hypothesis that Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is caused, directly or indirectly, by defects in brain metabolism. Interest in the hypothesis has been spurred both by compelling evidence gathered over the past 20 years that metabolic defects in the brain are closely linked to the pathogenesis and symptoms of AD and by the overwhelming failure of the dominant amyloid hypothesis to deliver effective treatments.

It has been known for at least 20 years that diabetics are at least twice as likely as their peers to develop AD. More recent research has illustrated this increased risk is specifically associated with poorly controlled diabetes and particularly with individuals who experience more frequent and severe disease state swings in glucose and insulin levels. This suggests defective patterns of glucose and insulin metabolism may play a role in AD development.

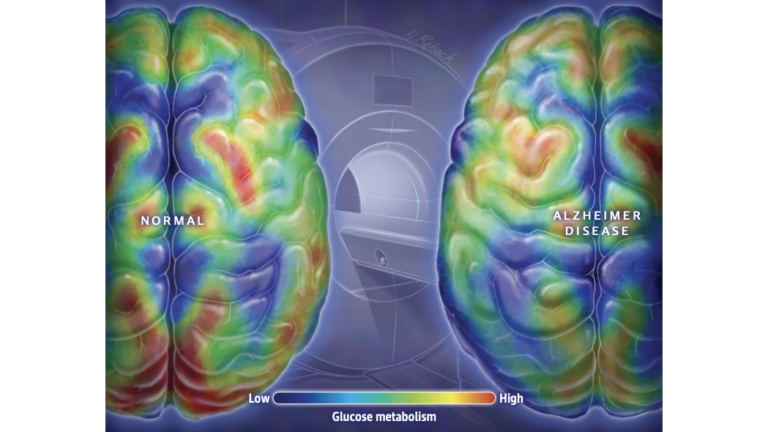

Figure 1: It is well established that the brains of individuals with AD display lower levels of glucose metabolism throughout, and particularly in regions associated with memory and executive function.

Since at least 2003, some researchers have characterized AD as Type 3 diabetes, arguing the brains of individuals with AD show impairments in glucose metabolism and insulin signaling similar to those seen in the periphery (i.e., cells outside the central nervous system) of Type 1 and Type 2 diabetics. Similarly, it is uncontroversial that compared to their peers without cognitive impairment, the brains of AD patients have lower levels of glucose metabolism and insulin signaling, particularly in the regions of the brain associated with memory storage and executive function. Supporters of the Type 3 diabetes hypothesis argue these deficits are not merely biomarkers and instead play a direct causal role in the disease.

As reviewed previously on CrossFit.com, loss of glucose metabolism and/or insulin signaling can directly lead to loss of neuronal function, impaired cell health, and the accumulation of amyloid beta plaques and hyperphosphorylated tau tangles — all established markers of AD progression. Poor metabolic health may also contribute to poor sleep, vascular defects, and inflammation, all of which have been independently linked to AD.

Impairments in glucose metabolism may also explain the significance of the most well-established genetic risk factor for AD. ApoE, which codes for a protein that regulates lipid metabolism, codes for three alleles: ApoE2, ApoE3, and ApoE4. ApoE3 is the most common in the general population. ApoE2 is highly protective against Alzheimer’s, while ApoE4 significantly increases AD risk. Recent mouse research indicates the brains of mice carrying the ApoE2 allele showed increased glucose transport into brain cells and increased glycolytic activity within brain cells. Conversely, ApoE4 carriers have lower levels of glucose transport and glycolysis. As a result, the brains of ApoE2 carriers are more robust amid metabolic challenges, while the brains of ApoE4 carriers more easily become malnourished in response to deficits in glucose availability, glucose transport, and/or insulin signaling. These energy deficiencies have been linked to synapse loss and cognitive impairment.

This hypothesis has not yet yielded an effective treatment for AD. In 2018, a trial testing pioglitazone, which lowers blood glucose levels, was stopped early when it became clear it did not have a significant benefit in patients. Recent and ongoing research is testing intranasal insulin, which delivers insulin directly to the brain and so rapidly ameliorates some forms of insulin resistance; early results have been promising but inconsistent. Other teams have tested the ketogenic diet and other metabolic therapies, which have shown promising but preliminary effects on biomarkers of AD and reversal of AD symptoms. Consequently, the idea that impairments in glucose metabolism can lead to the development of AD remains an interesting and promising hypothesis, but it is yet to be rigorously tested.