This 2019 review summarizes potential mechanisms linking Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes.

Neurodegeneration will develop in 29% of diabetics at some point in their lives (1). Brain insulin resistance is associated with Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive impairment, and the regions of the brain most closely associated with Alzheimer’s pathology — the hippocampus, hypothalamus, and cortex — are also the regions richest in insulin receptors (2). The review authors argue these associations may be causal and explore ways hyperglycemia and impaired brain insulin signaling may directly contribute to cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease.

Insulin signaling in the brain triggers neuronal development and synaptic plasticity, while impaired insulin signaling is associated with reduced vascular development (3). Decreased vascular development can itself lead to neuronal inflammation and synapse loss by impairing nutrient transport to and from brain cells (4). Broadly, insufficient insulin activity in the brain and hippocampus specifically has been associated with neurodegeneration, cognitive impairment, and impairments in memory formation (5).

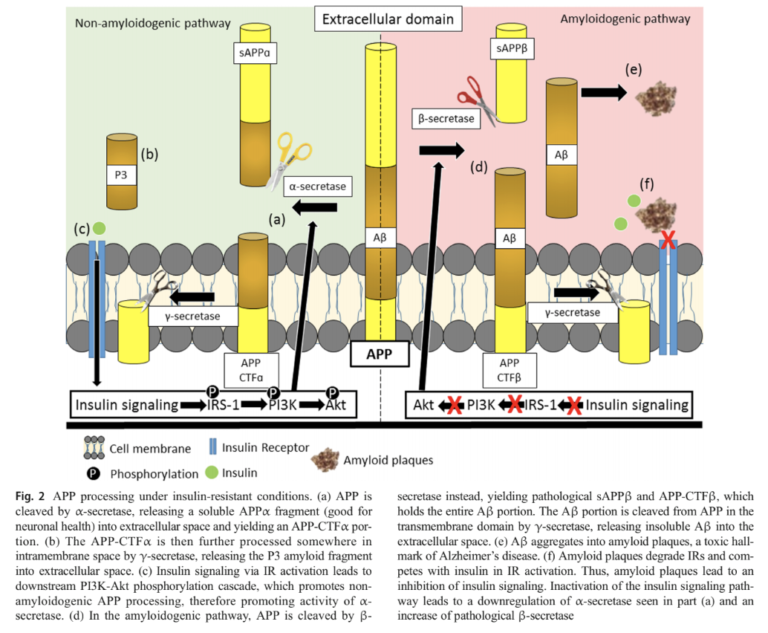

As summarized in the figure below, impairments in the insulin signaling cascade — which involves activation of IRS-1, PI3K, Akt and a variety of other proteins and enzymes — can also be directly linked to multiple elements of Alzheimer’s pathology, including the accumulation of amyloid beta (AB) plaques and hyperphosphorylated tau neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs).

Dysfunctional insulin signaling directly contributes to amyloid beta accumulation. When amyloid precursor protein (APP, the primary function of which is not completely understood) is cleaved in the context of high insulin signaling, it produces a soluble remnant the cell can eliminate. When insulin signaling is deficient, this cleavage instead forms an insoluble amyloid-beta protein fragment, which over time leads to amyloid plaque formation. One of the consequences of these amyloid plaques is impaired insulin receptor functionality. Thus, insulin resistance and amyloid plaque development form a vicious cycle in which initial insulin resistance leads to plaque development, which leads to further insulin resistance (6).

Dysfunctional insulin signaling directly contributes to amyloid beta accumulation. When amyloid precursor protein (APP, the primary function of which is not completely understood) is cleaved in the context of high insulin signaling, it produces a soluble remnant the cell can eliminate. When insulin signaling is deficient, this cleavage instead forms an insoluble amyloid-beta protein fragment, which over time leads to amyloid plaque formation. One of the consequences of these amyloid plaques is impaired insulin receptor functionality. Thus, insulin resistance and amyloid plaque development form a vicious cycle in which initial insulin resistance leads to plaque development, which leads to further insulin resistance (6).

Insulin signaling similarly activates GSK3B, a protein that decreases hyperphosphorylation of tau (the first step toward development of pathological neurofibrillary tangles); thus, impaired insulin signaling allows NFT accumulation (7).

The authors briefly explore additional mechanisms, noting advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) and decreased sirtuin activity may lead to insulin resistance and increased tau accumulation (8). Increased AGE activity and decreased sirtuin activity are known consequences of diabetes and insulin resistance.

Notably, ApoE4, the strongest genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s, leads to insulin resistance by decreasing the availability of insulin receptors at the cellular level (9).

The majority of the data supporting these mechanisms has been drawn from animal and in vitro models, thus reflecting the preliminary nature of the hypothesis. Taken together, this early research nonetheless illustrates a variety of mechanisms by which diabetes and/or insulin resistance could directly contribute to the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

Takeaway: Research on the link between insulin resistance and Alzheimer’s disease remains promising but preliminary. However, given the lack of viable alternatives to prevent or treat Alzheimer’s disease and the failure of other theoretical frameworks to deliver clinical improvements, the hypothesis that Alzheimer’s is at least partially the result of insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, or the downstream consequences thereof deserves further exploration.