Observational evidence has suggested a poor diet is associated with increased risk of depression, a high-quality diet is associated with reduced risk, and these effects are independent of reverse causality — e.g., the association between dietary quality and socioeconomic status (1). Data from animal trials has suggested improving dietary quality can ameliorate the symptoms of depression (2), and lifestyle interventions including dietary change have been found beneficial in humans (3). The SMILES trial was a small, randomized trial designed to test the specific impact of dietary change in the treatment of major depression.

Researchers randomized 67 New Zealand residents to one of two arms for the 12-week trial period. One group was prescribed the “ModiMedDiet,” based on Australian dietary guidelines. This diet focused on general improvements in dietary quality and encouraged a balanced diet high in fruits, vegetables, and other high-quality foods (4). Subjects in this group received four weekly dietary support sessions followed by three biweekly sessions. Controls received a “befriending” protocol, in which the same amount of time was spent talking, playing games, and completing similar activities with a member of the trial staff. This “befriending” protocol is commonly used as a control group in psychotherapy trials and is designed to control for differences in time allocated, client expectancy, and therapist interaction between the two groups. All subjects were 18 years or older, diagnosed with major depression, and scored low on a scaled evaluation of dietary quality prior to enrolling (5, 6). Subjects who were bipolar or had a similar condition were excluded. Subjects who were receiving treatment for depression continued treatment throughout the trial.

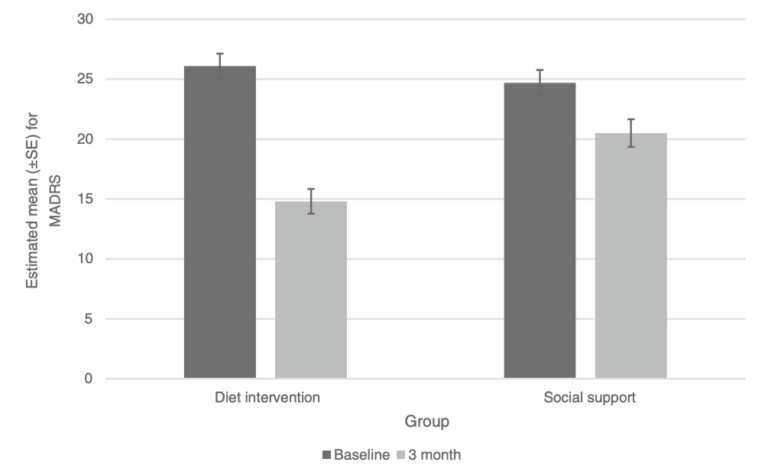

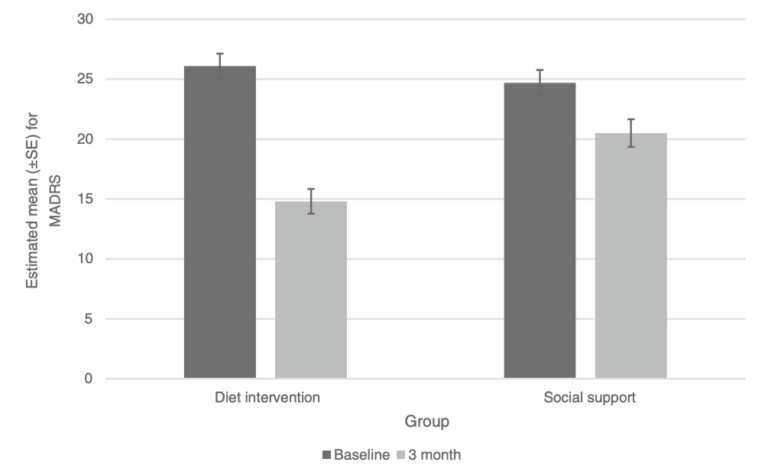

The primary outcome was improvement in the MADRS scale, a validated, interviewer-rated assessment of 10 items on a 6-point scale, with higher scores indicating more severe depression (7). The dietary intervention group showed an average of 7.1 points greater improvement in MADRS score. Participants also self-reported improvements in symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Figure 1: Mean MADRS scores before and after 12-week dietary and control (social support) interventions. The improvement in MADRS score was significantly greater in the dietary intervention group.

These results suggest a dietary therapy alone can lead to significant improvements in some measures of depression in as little as 12 weeks. These results are consistent with previous research suggesting diet can be an effective tool, both by itself and alongside other therapies, to ameliorate and/or reverse depressive states (8). Subjects following this diet did not lose significant amounts of weight, and no significant improvements were observed in any markers of cardiovascular risk or metabolic health. This suggests these improvements are independent of such factors. Instead, the link between diet and mood may be mediated by changes related to inflammation, oxidation, and the direct effects of diet on brain plasticity (9). Notably, the researchers found the “ModiMedDiet” was cheaper than the average of the diets participants had been following prior to enrollment, which suggests this intervention may be broadly applicable (10).

This trial was small and therefore limited in its ability to detect whether diet has a significant impact on measures of depression severity. Future trials can test the generalizability, robustness, and longevity of these effects. More importantly, given the established link between metabolic disease and depression, as previously reviewed on CrossFit.com, it is plausible that diets leading to greater metabolic improvements may simultaneously lead to greater improvements in depression.