Currently, more than two-thirds of Americans are overweight, and one-third are obese (1). More than 30 million Americans are diabetic and 100 million are prediabetic (2). Treatment of diabetes and its related comorbidities accounts for one in every three Medicare dollars and one in every five health-care dollars spent (3). The metabolic syndrome, or “carbohydrate intolerance” as some have called it (4), is associated with a variety of specific maladies, including inflammation, vascular dysfunction, NAFLD, POCS, sleep apnea, and a general decline in health (5). Most mainstream diabetes organizations frame diabetes as a purely progressive condition that inevitably leads to a decline in health and organ failure (6). This is, in fact, consistent with the effectiveness of diabetes treatment using traditional approaches; a Kaiser Permanente study found only 0.007% of subjects reversed their diabetes without bariatric surgery over seven years (7).

Low-carbohydrate diets are increasingly well established as a tool to reverse metabolic disease, including diabetes (8). For example, one recent trial found more than half of diabetic patients who adhered to a ketogenic diet reduced their HbA1c to nondiabetic levels and were able to stop taking glucose-lowering medication and/or insulin (9). Low-carbohydrate diets have been discouraged by some of the same diabetes organizations noted above, often due to the fact that they increase total and LDL cholesterol and are thereby thought to increase heart disease risk. These same diets also, however, generally increase HDL, reduce triglycerides, and so reduce the HDL:TG ratio. This ratio has been found to be more predictive of heart disease risk than either LDL or total cholesterol, both of which have received only weak and inconsistent support as markers for heart disease risk or risk modification targets in more recent studies (10).

In light of this evidence, this 2019 survey assessed the impact of a low-carbohydrate diet on weight, health, and quality of life.

Researchers surveyed 1,580 subjects who were sourced through social media and word of mouth, primarily through the networks of clinicians who prescribed low-carbohydrate diets for weight loss and health improvement. Subjects were surveyed to assess the amount of carbohydrate they consumed each day; the impact of a low-carbohydrate diet on their body weight and a variety of biomarkers; and the impact of a low-carbohydrate diet on subjective measures of well-being, independence, and quality of life.

Approximately 80% of those surveyed reported following a diet that would be expected to induce ketosis, consuming fewer than 50 grams of carbohydrate per day. Three out of four subjects initiated the diet primarily to lose weight, and a smaller percentage sought improvements to chronic disease symptoms and energy levels.

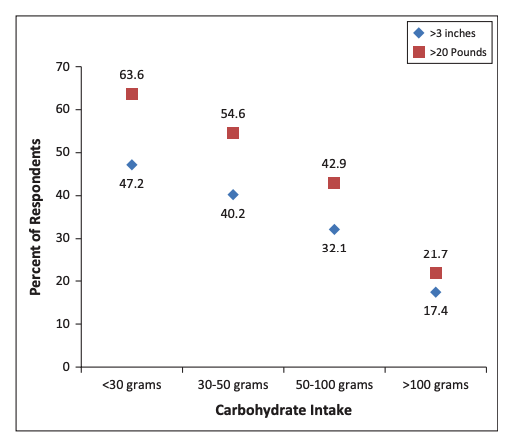

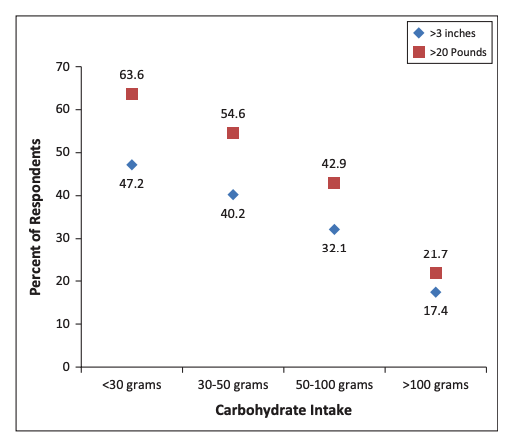

More than one-third of subjects lost at least 30 pounds following a low-carb diet, and nearly three-quarters lost at least 10 pounds. As shown in the figure below, weight loss was greater among subjects who restricted carbohydrate intake to a greater extent, with more than half of all subjects who ate fewer than 50 grams of carbohydrate per day losing at least 20 pounds.

Figure 1: Relationship between daily carbohydrate intake and frequency of significant weight loss

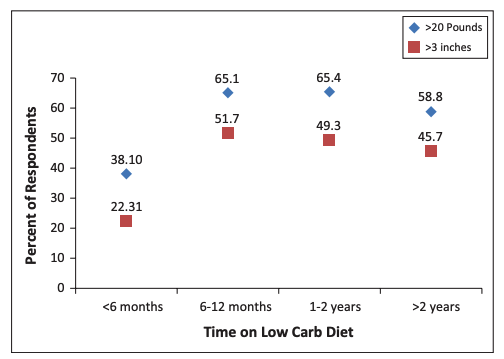

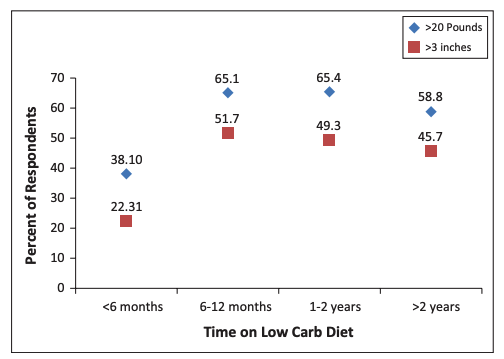

Weight loss was well maintained among the subjects surveyed, with more than half of those who remained on the diet for at least two years reporting a loss of 20 pounds or more.

Figure 2: Relationship between length of time on the diet and significant weight loss

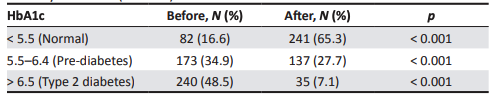

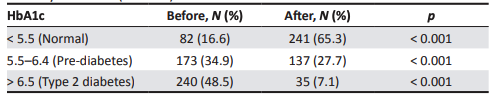

Glycemic control improved substantially as well. Prior to initiating the diet, 48.5% of subjects had a diabetic HbA1c (> 6.5%), and only 16.6% had normal HbA1c (< 5.5%). The low-carb diet reversed these proportions, with 65.3% of subjects reporting a normal HbA1c after following the low-carb diet and only 7.1% remaining diabetic. As was true of weight loss on the diet, greater carbohydrate restriction led to greater glycemic improvements, with the rate of HbA1c normalization greatest among those consuming fewer than 30 grams of carbohydrate per day.

Table 3: The proportion of subjects with normal, prediabetic or diabetic HbA1c before and after the low-carb diet. Note HbA1c values were only recorded both before and after dieting for 495 subjects.

Subjects reported significant reductions in medication use. The share of subjects using antidepressants (12.5% to 5.8%), anti-anxiety medication (7.3% to 3.4%), sleep aids (11.4% to 4.8%), painkillers (22.1% to 5.0%), or anti-inflammatory medication (27.1% to 6.8%) all decreased significantly.

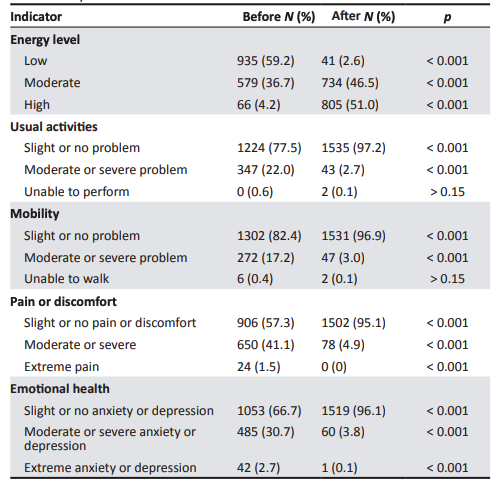

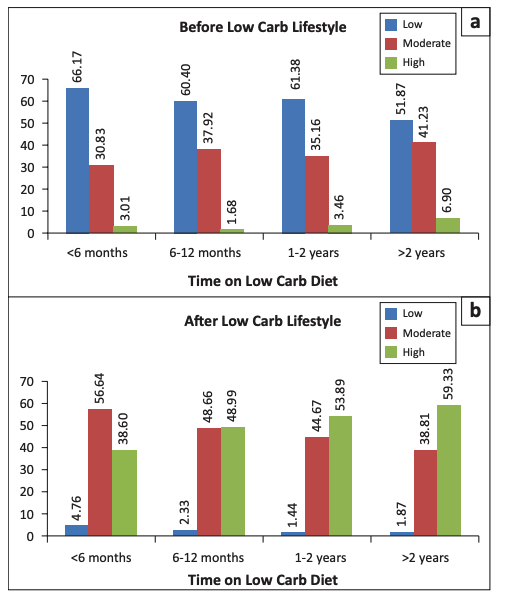

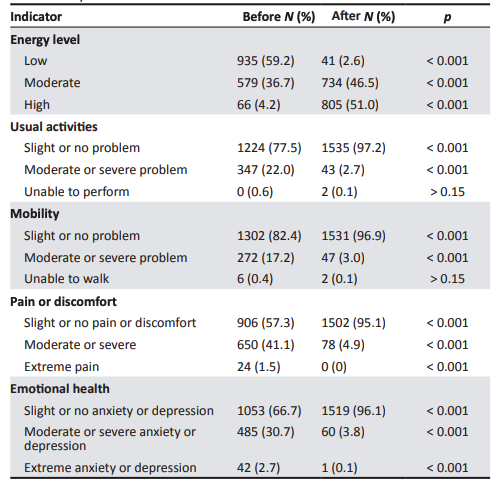

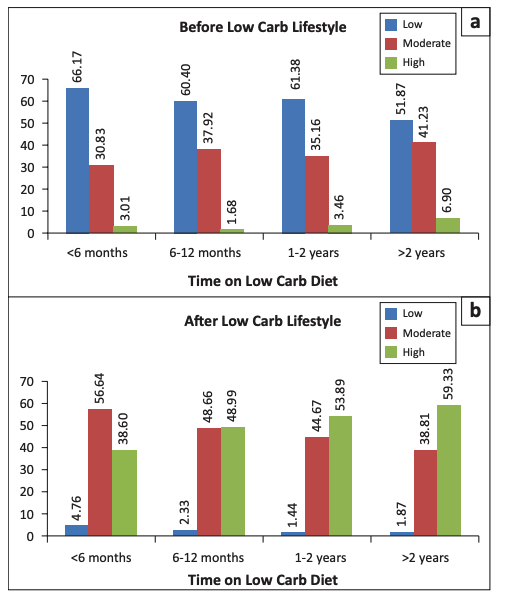

Subjects also reported significant improvement across a variety of measures of quality of life. Energy levels improved in many subjects, with the majority of subjects reporting low energy levels prior to initiating a low-carb diet and high energy levels after following the diet for at least one year (See Table 4 and Figure 5 below). There were significant reductions in the share of subjects who reported problems completing daily activities (22.0% to 2.7%); moderate or severe mobility problems (17.2% to 3.0%); moderate, severe, or extreme pain or discomfort (42.6% to 4.9%); and moderate, severe, or extreme anxiety or depression (33.4% to 3.9%). In addition to improving quality of life, these changes have been associated with improved longevity (11) and are consistent with previous evidence indicating low-carbohydrate diets may be a promising treatment option to improve mental health without pharmacotherapy (12).

Table 4: Changes to various markers pertaining to energy level and physical and emotional well-being before and after following a low-carb diet

Figure 5: Share of subjects reporting low, moderate, or high energy levels before and after a low-carb diet

Subjects also reported they experienced less hunger, tiredness, difficulty concentrating, or irritability between meals on a low-carb diet than they had on their previous diet.

While subjects’ total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol increased, HDL cholesterol increased from 57 to 71 mg/dL while triglyceride levels dropped from 149 to 82 mg/dL. As noted above, these changes — in particular, the reduction in the TG:HDL ratio from 3.49 to 1.37 — reflect a reduction in overall cardiovascular risk.

Subjects also reported anecdotal improvements across a variety of other conditions for which low-carb diets have provided benefits, including migraines (13), IBS (14), heartburn (15), POCS (16), NAFLD (17), and chronic pain (18).

This study is confounded by major potential biases. As the study drew data from self-selected subjects sourced through channels favorable to low-carb diets (i.e., the networks of clinicians known to prescribe low-carb diets), these subjects were almost certainly more compliant and received more positive results than a representative selection of low-carb dieters. Much of the data was derived from self-reporting, which may introduce additional deviation from actual clinical changes.

With these caveats in mind, however, it remains clear that low-carb diets can, in at least some subjects, generate greater improvements in metabolic health, mental health, functionality, and quality of life than generally can be achieved by traditional therapies. The survey indicates the core premises associated with some of these conditions — such as the belief that diabetes is irreversible — are unfounded. It also indicates low-carb diets have the potential for substantial clinical benefit and are worth consideration by patients or clinicians looking to improve metabolic, mental, or overall health.