In this October 2018 editorial in Frontiers in Psychiatry, Michael Hengartner and Martin Plöderl argue trials investigating the impact of antidepressants show statistically significant but not clinically significant effects, and even these meager effects may be eroded by known biases.

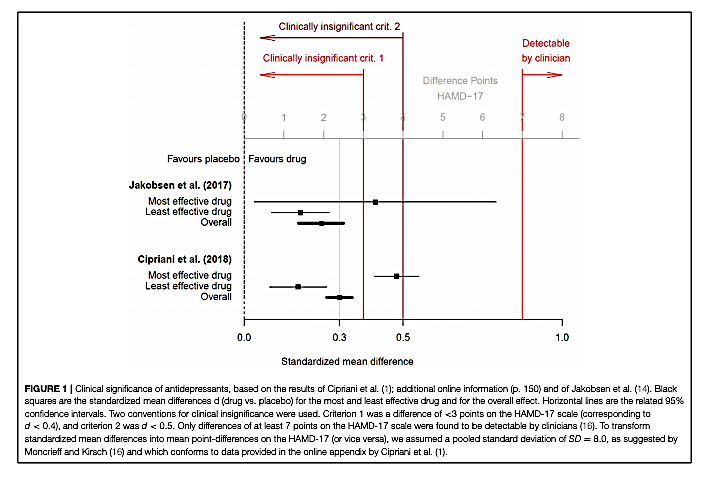

The authors present the data from two recent meta-analyses summarizing the impact of antidepressant medications on measures of clinical depression (1). Both meta-analyses found antidepressants had statistically significant benefits compared to placebo, but both also found a small mean effect size, equal to or below d = 0.3. Hengartner and Plöderl note this small mean effect size is similar to the effect size observed in previous meta-analyses, as cited by A. Cipriani (1), and corresponds to an improvement of approximately 2 points on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D 17).

The meta-analyses authors and others have argued improvements in HAM-D scores of less than 3 points (equivalent to an effect size of d = 0.5) are clinically irrelevant, and improvements of less than 7 points are not clinically detectable (2). By this standard, Hengartner and Plöderl argue the mean benefit associated with antidepressant treatments is below the threshold for clinical significance.

Even this small effect size, Hengartner and Plöderl argue, may be inflated due to widely recognized biases that exaggerate the perceived impact of antidepressant drugs in clinical trials. Blinding is difficult in antidepressant trials, as trial staff and even patients can often detect placebo use by a lack of side effects; when active placebos are used that provide the same side effects as antidepressants, the effect size shrinks (3). Additionally, trials that have assessed patients’ own perception of benefit have shown smaller effects than those relying on clinicians’ assessment of benefit (4).

These and other possible biases, combined with the small baseline effect size, have led some to argue bias accounts for the majority of the perceived benefits of antidepressants in clinical trials (5).

Importantly, these uncertain benefits come with certain costs, as previously discussed on CrossFit.com. Antidepressants have been associated with increased risk of dementia, stroke, obesity, and all-cause mortality. These side effects may be a worthwhile trade-off for a subset of patients who benefit from antidepressants, but the evidence suggests the majority of patients experience benefits that are of little to no clinical significance.

References

- Cipriani A, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2018 Apr 7;391(10128): 1357-1366.

- Moncrieff J, Kirsch I. Empirically derived criteria cast doubt on the clinical significance of antidepressant-placebo differences.

Contemp Clin Trials. 2015 Jul;43: 60-2. - Moncrieff J, Wessely S, Hardy R. Active placebos versus antidepressants for depression.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(1): CD003012.

- Barbui C, Furukawa TA, Cipriani A. Effectiveness of paroxetine in the treatment of acute major depression in adults: a systematic re-examination of published and unpublished data from randomized trials. CMAJ. 2008 Jan 29;178(3): 296-305.

- Gøtzsche, P. Why I think antidepressants do more harm than good. Lancet 1.2 (July 2014): 104-6.

Comments on Statistically Significant Antidepressant-Placebo Differences on Subjective Symptom-Rating Scales Do Not Prove that the Drugs Work: Effect Size and Method Bias Matter!

1 Comments