In a now famous paper, Dr. Loren Cordain et al. share their research into how the eyesight of hunter-gatherer groups compares to industrialized populations. Myopia, the most common eye problem worldwide, affects 40% of the U.S. population. In hunter-gatherer groups, rates are typically only 0-2%, and cases are less severe.

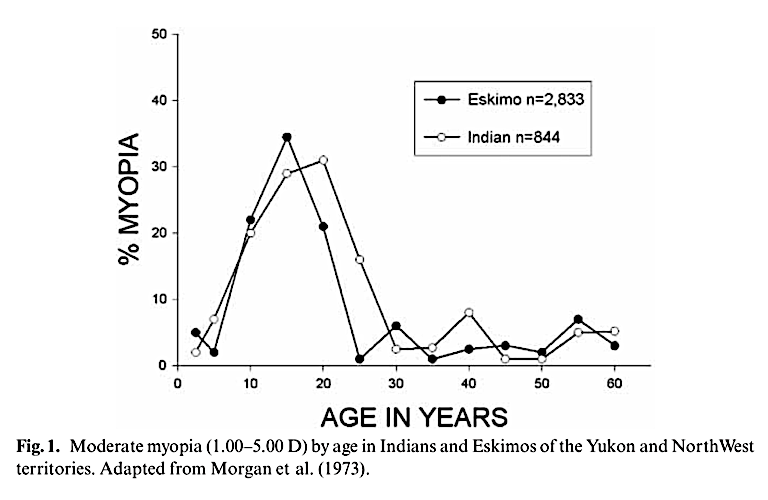

In a natural experiment, researchers observed changes in eyesight among indigenous populations as they adopted a Western style of living. This includes the addition of foods containing sugar and highly refined grains, which do not exist in the natural environment. Rates of myopia skyrocketed post-Westernization, reaching levels typical of industrialized populations within a generation. The high prevalence of myopia found in children is not seen in their grandparents who grew up on a native diet.

Myopia, commonly called nearsightedness, results from the over-lengthening of the eyeball or excessive curvature of the cornea. Due to these defects, light rays do not focus properly on the retina, which leads to blurred vision. Excessive near work, such as reading, is widely believed to cause myopia. To see if this is true, the researchers compared populations in outlying areas where people were literate but maintained their traditional diet with populations including urban children who were literate and had access to Western food products. Myopia rates were seven times higher among the urban children (2.9% vs. 21.7%). This supports the hypothesis that diet is a factor in the development of myopia. Cordain et al. share their findings regarding carbohydrate consumption in these populations:

In [a] study of 229 hunter-gatherer societies … although refined cereals and sugars were rarely if ever consumed by groups living in their traditional manner, these foods quickly became dietary staples following western contact. Schaefer (1971; 1977) has shown that, in two Eskimo groups undergoing western acculturation, the per capita consumption of sugar in all forms increased from 11.8 kg in 1959 to 47.4 kg in 1967. The same groups’ per capita consumption of cereals and flour products increased from 71.0 kg in 1959 to 80.0 kg in 1967. Prior to western contact, neither of these carbohydrates was ever consumed (Stefansson 1919).

In the U.S., rates of myopia have increased from 25% in the 1970s to 40% in 2000 (1). This coincides with the steady increase of carbohydrates in the standard American diet over the same time period.

The proposed mechanism behind the dietary contribution to myopia is hyperinsulinemia. Excessive insulin triggers an increase in free IGF-1, a hormone that regulates tissue growth. Insulin has been shown in animal models to promote elongation of the eyeball, whereas insulin’s antagonist, glucagon, has been shown to promote hyperopia (shortening of the eyeball) (2).

Researchers have also linked sugar to other eye conditions, such as glaucoma, cataracts, diabetic retinopathy, and macular degeneration. Carbohydrates bind to proteins and fats in a process called glycation. This process happens non-enzymatically in the body, which is to say haphazardly and disastrously, like pouring sugar into a gas tank. Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) have been shown to accumulate in the eye. This accumulation can lead to cloudiness and brown spots in the lens of the eye.

As R. H. Nagaraj et al. explain in “The pathogenic role of Maillard reaction in the aging eye”:

The proteins of the human eye are highly susceptible to the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) from the reaction of sugars and carbonyl compounds. AGEs progressively accumulate in the aging lens and retina and accumulate at a higher rate in diseases that adversely affect vision such as, cataract, diabetic retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration. In the lens AGEs induce irreversible changes in structural proteins, which lead to lens protein aggregation and formation of high-molecular-weight aggregates that scatter light and impede vision. In the retina AGEs modify intra- and extracellular proteins that lead to an increase in oxidative stress and formation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which promote vascular dysfunction. (3)

Nagaraj and colleagues widely recommend eliminating high glycemic index (GI) foods from the diet. These foods release sugar rapidly into the bloodstream, and the body compensates by releasing large amounts of insulin quickly. Fructose has been found to cause up to 10 times as much glycation as glucose. The researchers suggest consuming lots of vegetables, some fruit, and zero high fructose corn syrup is advisable. Research on the relationship between eye sight and low-carbohydrate or ketogenic diets is in the preliminary stages, with one study showing improvement in mice susceptible to glaucoma (4).